Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

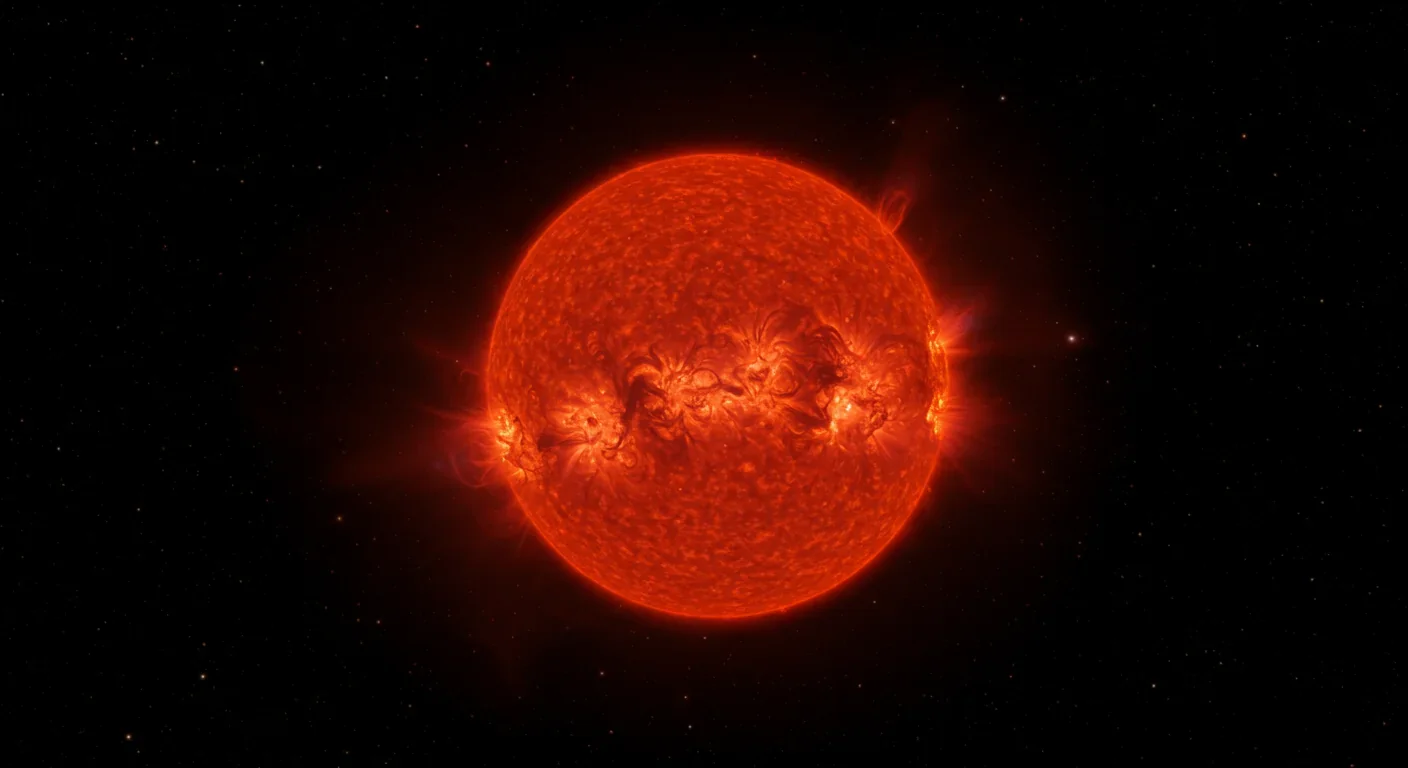

TL;DR: Betelgeuse's 2019-2020 Great Dimming wasn't a sign of imminent supernova but a massive dust cloud formed by stellar ejection. Astronomers watched in real-time as the red supergiant expelled material equal to several Moon masses, revealing how dying stars shed mass.

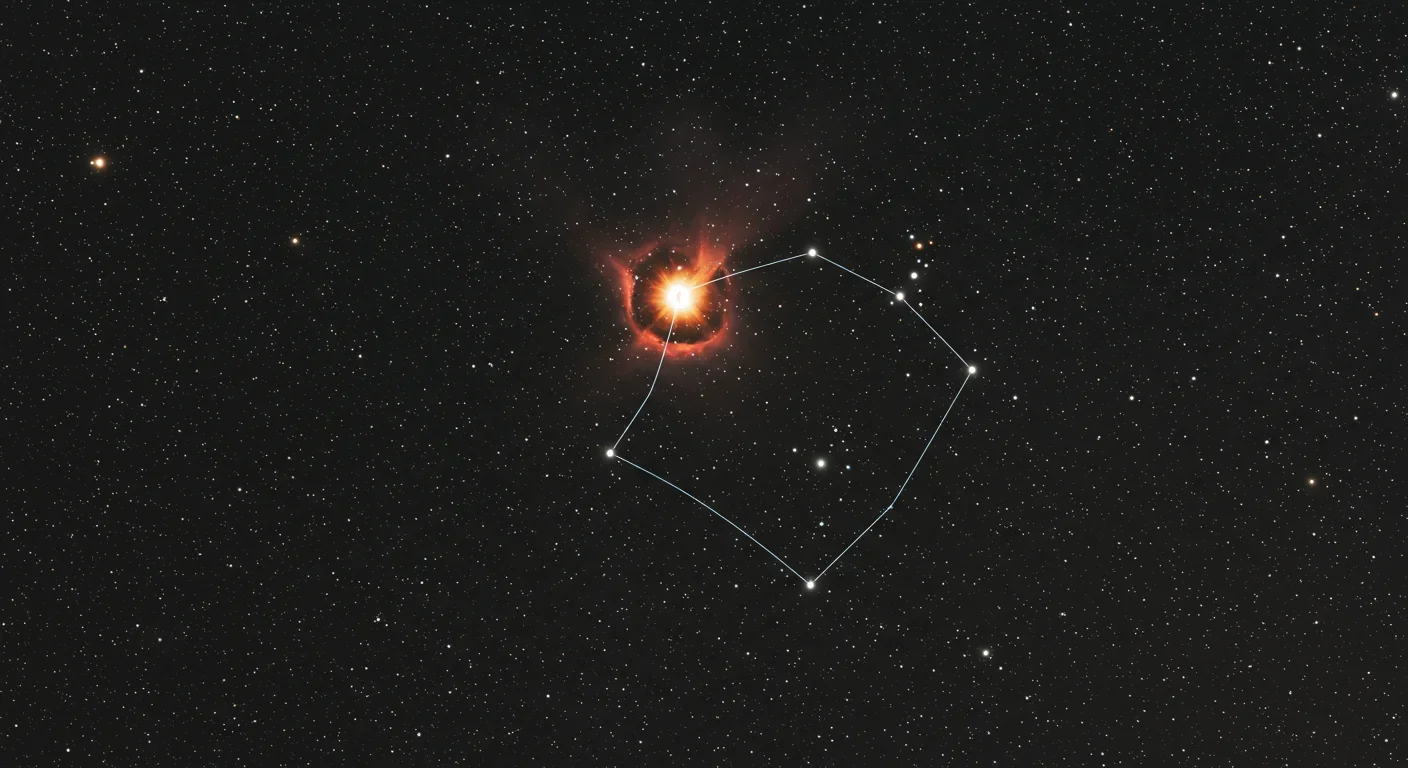

Late in 2019, astronomers around the world watched in astonishment as one of the night sky's most familiar stars started to fade. Betelgeuse, the bright red shoulder of Orion, began dimming so dramatically that even casual stargazers noticed something was wrong. Within months, this stellar giant had lost more than 60% of its light - an unprecedented drop that sent speculation spiraling toward one captivating question: Was this massive star about to explode?

What scientists discovered instead turned out to be equally fascinating, revealing how even nearby stars can surprise us with violent behavior we're only beginning to understand.

In October 2019, Betelgeuse started its dramatic fade. By mid-February 2020, the star had dimmed to roughly 35-40% of its normal brightness - a loss so severe it would have been like the Sun suddenly becoming fainter than Venus appears to us. For a star that had been reliably bright for centuries of recorded observations, this represented an astronomical puzzle of the highest order.

The dimming wasn't subtle. Astronomers tracking the star saw its magnitude drop by more than 1.5 units, making it visibly darker to the naked eye. Amateur astronomers comparing Betelgeuse to nearby stars reported the change within weeks, while professional observatories scrambled to redirect their most powerful instruments toward Orion.

The event became known as the Great Dimming, and it triggered one of the most intensive observational campaigns in modern astronomy.

Betelgeuse lost more than 60% of its brightness in just a few months - enough that backyard astronomers could see the difference with their naked eyes.

To understand why this dimming mattered so much, you need to understand what Betelgeuse is. Located roughly 700 light-years from Earth, Betelgeuse is a red supergiant - one of the largest types of stars in the universe. If you placed it at the center of our solar system, its surface would extend past the orbit of Jupiter.

The star weighs in at roughly 15-20 times the mass of our Sun but has swollen to about 700 times its radius. This bloating happens because Betelgeuse has exhausted the hydrogen fuel in its core and moved on to burning heavier elements. It's in the final stages of stellar life, a phase that will end - perhaps in the next 100,000 years - in a spectacular supernova explosion.

That timeline matters. When a red supergiant dims dramatically, astronomers have to consider whether it's a sign of imminent collapse. Betelgeuse is close enough that when it does explode, it will briefly outshine the full Moon and be visible in daylight. So when the Great Dimming began, supernova speculation wasn't unreasonable - it was prudent.

The moment Betelgeuse's dimming became clear, observatories worldwide mobilized. The challenge was enormous: figure out what was happening inside or around a star located 700 light-years away - a distance so vast that light from the event had actually left Betelgeuse around the year 1300 CE.

Researchers deployed every tool in the astronomical arsenal. The Hubble Space Telescope used its ultraviolet spectrographs to probe the star's outer atmosphere, searching for signs of unusual activity. The European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile employed its SPHERE instrument - an adaptive optics system capable of resolving features on Betelgeuse's surface - to capture images showing exactly which parts of the star were dimming.

Ground-based spectroscopy focused on measuring the star's temperature. If Betelgeuse was cooling down - perhaps as a prelude to collapse - that would show up as changes in its spectrum. The Lowell Discovery Telescope in Flagstaff recorded spectra on February 14, 2020, near the dimming's minimum, focusing on titanium oxide absorption lines that serve as reliable temperature indicators.

Each observatory added a piece to the puzzle, but the picture that emerged was more complex than anyone expected.

"We were seeing the appearance of a star changing in real-time on a scale of weeks."

- Miguel Montargès, Astronomer, Paris Observatory

The first major clue came from temperature measurements. When astronomers analyzed Betelgeuse's spectrum during the dimming, they found the star's effective surface temperature was about 3,325 degrees Celsius - only 50-100 degrees cooler than measurements taken in 2004, long before the dimming.

This was a bombshell. A 60% brightness drop should have corresponded to a massive temperature decrease if the star itself was dimming. But the temperature had barely budged. That pointed to a completely different explanation: something was blocking the light, not the star itself losing luminosity.

The answer was dust - vast clouds of it, formed from material ejected by the star itself.

High-resolution imaging from the Very Large Telescope showed an asymmetric dark patch concentrated over Betelgeuse's southern hemisphere. This wasn't a uniform dimming across the entire stellar surface - it was a localized shadow, like a veil had been drawn across part of the star. The dust cloud was estimated to block light from about 25% of Betelgeuse's visible surface.

But where did this dust come from, and why did it form so suddenly?

The star's temperature barely changed during the Great Dimming - proof that something was blocking the light rather than the star itself cooling down.

Hubble's observations held the key. Months before the visible dimming, in late 2019, Hubble's ultraviolet spectrographs detected something extraordinary: dense, superheated plasma moving through Betelgeuse's atmosphere at roughly 200,000 miles per hour.

This wasn't the star's normal stellar wind. This was a massive convective upwelling - a huge bubble of material rising from deep within the star and punching through its outer layers. Think of it like a solar prominence, but scaled up to match a star hundreds of times larger than the Sun.

The ejection event was staggering in scale. Researchers estimate Betelgeuse expelled 400 billion times more mass than a typical solar coronal mass ejection - a chunk of material weighing several times the mass of Earth's Moon, hurled into space at incredible velocities.

As this superhot plasma moved outward from the star's surface into cooler regions, it condensed. The result was a vast cloud of dust grains, each one tiny but collectively forming an opaque curtain that blocked starlight. By December 2019 and into early 2020, this dust cloud had positioned itself between Earth and Betelgeuse's southern hemisphere, causing the dramatic dimming observers saw.

The plasma ejection didn't happen in isolation. Betelgeuse's pulsation cycle likely played a role. Red supergiants like Betelgeuse are inherently unstable stars. Their outer layers expand and contract on regular cycles - in Betelgeuse's case, a primary cycle of roughly 400-420 days, plus additional shorter-term variations.

These pulsations are driven by the star's internal structure. Betelgeuse no longer burns hydrogen in a stable core like the Sun does. Instead, it's fusing heavier elements in a complex series of shells, each burning different fuels at different rates. This creates enormous convective cells - rising plumes of hot material and sinking currents of cooler gas - that constantly churn the star's interior and reach all the way to its surface.

When one of these convective cells reached Betelgeuse's surface at a time when the star was already expanding in its pulsation cycle, the conditions were right for a major ejection event. The upwelling broke through, carrying with it a huge mass of stellar material.

What's remarkable is that the ejection disrupted the star's fundamental pulsation, temporarily shortening the 400-day period. It was as if the star had hiccupped so violently that it threw off its normal rhythm - a sign of just how energetic the outburst was.

"We see this all the time in red supergiants, and it's a normal part of their life cycle - red supergiants will occasionally shed material from their surfaces, which will condense around the star as dust."

- Dr. Emily Levesque, Astrophysicist, University of Washington

One of the most striking aspects of the Great Dimming was the unprecedented detail with which astronomers observed it. "We were seeing the appearance of a star changing in real-time on a scale of weeks," said Miguel Montargès, who led one of the key observational teams using ESO's Very Large Telescope.

Previous studies of stellar mass loss had relied on looking at the aftermath - nebulae and shells surrounding stars, the remnants of ancient ejection events. But with Betelgeuse, astronomers caught the event in progress. High-resolution images captured the dust cloud forming, moving, and eventually dissipating. Spectroscopy tracked temperature changes across the stellar surface. Ultraviolet observations revealed the pre-ejection plasma surge.

This real-time monitoring was possible because of Betelgeuse's proximity and enormous size. At 700 light-years, it's one of the closest red supergiants to Earth. Combined with its massive diameter - about 700 times the Sun's - Betelgeuse is large enough that modern telescopes can actually resolve features on its surface, something impossible for almost any other star beyond our Sun.

The combination of visible-light imaging, infrared observations, ultraviolet spectroscopy, and interferometry created a multi-wavelength portrait of a star in crisis. Each technique revealed different aspects of the event, and together they told a coherent story.

By April 2020, Betelgeuse had returned to near-normal brightness. The dust cloud that caused the dimming had dispersed, blown outward by the star's powerful stellar wind or simply moved out of our line of sight as the star continued its rotation.

But the story didn't end there. Observations showed that Betelgeuse experienced a secondary, less dramatic dimming from mid-May to mid-July 2020. This suggested the star's behavior remained unsettled, possibly producing additional dust clouds or experiencing continued surface cooling.

These repeat events highlight an important reality: red supergiants regularly shed material from their surfaces, and this material often condenses into dust. The Great Dimming wasn't unique to Betelgeuse - it was an extreme example of normal red supergiant behavior.

Other massive stars show similar phenomena. Researchers studying extragalactic red supergiants have found bar-like nebulae and shocked emission analogous to features seen around Betelgeuse, suggesting that episodic mass loss and dust formation are common traits of stars in this evolutionary phase.

Betelgeuse ejected 400 billion times more mass than a typical solar eruption - a chunk of material several times heavier than Earth's Moon.

So was the Great Dimming a sign that Betelgeuse is about to explode? Almost certainly not.

The consensus among astronomers is that Betelgeuse will explode as a supernova sometime in the next 100,000 years - a blink of an eye in cosmic terms, but likely far enough in the future that no human alive today will witness it. The dimming event, dramatic as it was, fits within the expected behavior of a star in its red supergiant phase.

Still, the event taught astronomers valuable lessons about what to look for when monitoring massive stars. The pre-ejection plasma surge detected by Hubble, for instance, could serve as an early-warning signal for future dimming events - or, in other stars nearing collapse, potentially a precursor to more terminal instability.

Understanding mass loss is critical to supernova science because it determines how much material surrounds a star when it explodes. This circumstellar material shapes the supernova's light curve and spectrum, influencing how we use these explosions as cosmological tools. The dust and gas shed by red supergiants in the millennia before they explode create the environment into which the supernova blast wave will expand.

In Betelgeuse's case, astronomers now have direct evidence of how much mass a red supergiant can lose in a single event - information that will refine models of pre-supernova evolution for years to come.

Betelgeuse remains under close observation. Andrea Dupree, one of the lead researchers on the Hubble observations, noted: "I hope to continue studying the star in hopes of catching it eject another gas bubble." She's not alone - observatories worldwide have Betelgeuse on their monitoring lists, ready to respond to any future anomalies.

The star's normal variability continues. Its 400-day pulsation cycle has largely returned to its pre-dimming pattern, though subtle changes persist. Longer-term cycles - including a roughly five-year brightness variation - overlay the shorter pulsations, creating a complex pattern that astronomers are still working to fully characterize.

And there's always the possibility of another major ejection event. Red supergiants are inherently unpredictable, their massive convective cells and unstable outer layers constantly shifting. A second Great Dimming could happen tomorrow, or it might not occur for decades. Either way, when it does, telescopes will be ready.

Despite the progress in explaining the Great Dimming, significant mysteries remain. Astronomers still don't fully understand what triggers these massive ejection events. Was it purely the coincidence of a convective upwelling occurring during a pulsation maximum? Or is there a deeper mechanism at work, perhaps involving magnetic fields or rotational forces?

The composition and properties of the dust cloud are another area of active research. Spectroscopic data revealed titanium oxide absorption, but the exact size distribution and composition of dust grains remain uncertain. Different grain properties would affect how efficiently the dust blocks light and how long it persists in the circumstellar environment.

The asymmetry of the dimming also raises questions. Why was the dust cloud concentrated predominantly over the southern hemisphere? Does this reflect directional mass loss driven by rotation, large-scale magnetic structures, or the geometry of the convective cells that triggered the ejection?

And finally, there's the broader question of how common such events are. Betelgeuse is the closest red supergiant to Earth and one of the best-studied massive stars. But is it representative of other red supergiants, or is its behavior somehow unusual? Comparative studies of extragalactic red supergiants are beginning to provide context, but a larger statistical sample would help.

The Great Dimming story is ultimately about humanity's growing ability to observe and understand stars at scales that would have been unimaginable just decades ago. Modern telescopes equipped with adaptive optics, interferometry, and space-based ultraviolet cameras can now resolve individual features on stellar surfaces and track their evolution over human timescales.

This represents a profound shift in astronomy. For most of history, stars were points of light - distant, unchanging, fundamentally beyond detailed study. Now, we can watch a star's surface evolve week by week, measure the velocities of material ejected from its atmosphere, and track dust clouds as they form and disperse.

Betelgeuse's Great Dimming was a reminder that even familiar stars can surprise us, that our nearest stellar neighbors are dynamic systems undergoing constant, sometimes violent change. It showed us that episodic mass loss shapes the final years of massive stars, creating the complex circumstellar environments that will ultimately channel and shape the supernova explosions to come.

And it gave us a preview of the kind of science we'll be able to do as telescopes grow even more powerful. The James Webb Space Telescope, with its unprecedented infrared sensitivity, will be able to study circumstellar dust in extraordinary detail. The next generation of extremely large telescopes - the European Extremely Large Telescope, the Thirty Meter Telescope, the Giant Magellan Telescope - will resolve stellar surfaces with even greater clarity.

When Betelgeuse does finally explode, perhaps 100,000 years from now, the initial flash of light will race toward Earth at 186,000 miles per second. For the brief time it takes that light to traverse the 700 light-years between star and observer, Betelgeuse will be a supernova in progress, its core collapsing, its outer layers blasting into space at a significant fraction of the speed of light.

Whoever is around to observe that event - humans, our descendants, or some other intelligence entirely - will have the Great Dimming's legacy to thank for part of their understanding. Every telescope pointed at Betelgeuse today, every spectrum captured, every dust cloud analyzed, is building the foundation for the science of tomorrow.

For now, Betelgeuse shines in Orion's shoulder, a red beacon marking winter nights. It pulses and dims and flares according to the chaotic rhythms of a dying star. And somewhere, right now, an astronomer is watching - waiting to see what it will do next.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.