Ice Volcano on Ceres Hints at Hidden Ocean

TL;DR: Jupiter's moon Ganymede harbors a 100-kilometer-deep ocean containing nine times more water than all of Earth's oceans combined. Scientists discovered this saltwater sea using magnetic field measurements and confirmed it through multiple space missions, making Ganymede a prime candidate in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Beneath a frozen crust thicker than Mount Everest is tall, Jupiter's moon Ganymede harbors a secret that makes Earth's oceans look like puddles. Scientists have confirmed that this distant moon contains a subsurface ocean holding more water than all of Earth's seas combined - a revelation that's transforming how we think about where life might exist beyond our planet.

The numbers are staggering. Ganymede's ocean stretches 100 kilometers deep - ten times deeper than Earth's deepest ocean trenches. That's an underwater realm containing roughly 11.4 billion cubic kilometers of water, compared to Earth's 1.3 billion. If you could drain Ganymede's ocean and pour it onto our planet, you'd raise sea levels by thousands of meters.

But here's what makes this discovery truly remarkable: this isn't just frozen water locked in ice. It's a liquid ocean, possibly warm, definitely salty, and potentially teeming with the chemical ingredients necessary for life.

You can't exactly send a submarine to Jupiter's moons. Instead, scientists had to get creative, using one of the universe's most elegant tricks: magnetism.

When NASA's Galileo spacecraft flew past Ganymede in the 1990s, it detected something extraordinary. The moon wasn't just reflecting Jupiter's powerful magnetic field - it was creating its own. This made Ganymede the only moon in our solar system with an intrinsic magnetic field, a feature usually reserved for planets.

But Galileo found something else. As Jupiter's magnetic field swept across Ganymede, it induced a secondary magnetic signature, a telltale sign of a conductive layer beneath the surface. The only substance that could produce such a strong signal? Saltwater.

Think about how a metal detector works. When electromagnetic waves encounter conductive material, they generate a response. Ganymede's ocean acts like a giant conductor buried beneath the ice.

Think about how a metal detector works. When electromagnetic waves encounter conductive material, they generate a response. Ganymede's induced magnetic field - measuring about 60 nanoteslas, half the strength of Jupiter's ambient field - could only exist if a vast, electrically conductive ocean lay hidden beneath the ice.

In 2015, the Hubble Space Telescope provided independent confirmation. By studying how Ganymede's auroras wobbled in response to Jupiter's magnetic field, astronomers could map the interior structure. The auroral behavior matched perfectly with models predicting a subsurface ocean.

Ganymede's internal structure reads like something from science fiction. Picture a rocky core roughly the size of Earth's moon, surrounded by a metallic layer that generates the magnetic field. Above that? An ocean deeper than anything on Earth. And topping it all off, a 150-kilometer-thick ice shell - thicker than the entire height of the International Space Station's orbit above Earth.

But recent discoveries suggest the reality is even stranger. Scientists now believe Ganymede might not have just one ocean, but several stacked layers separated by different phases of ice.

At the crushing pressures found deep inside Ganymede, water ice doesn't behave like the stuff in your freezer. It crystallizes into exotic forms - Ice II, Ice III, Ice V, Ice VI - each with different densities and structures. These high-pressure ice layers might separate multiple liquid oceans, creating what researchers describe as "a club sandwich" of water and ice.

The deepest ocean likely sits directly against the rocky mantle. This is huge for astrobiology because water-rock contact enables chemical reactions that could generate the energy and nutrients life needs.

What's actually in Ganymede's ocean? We're still piecing that together, but the clues are promising.

The magnetic field data tells us the ocean is salty - electrically conductive enough to generate that 60-nanotesla induced field. But in 2021, NASA's Juno spacecraft took the analysis further. Flying past Ganymede, Juno's instruments detected surface salts including hydrated sodium chloride (table salt), ammonium chloride, and sodium bicarbonate.

"The ocean is thought to have more water than all the water on Earth's surface, buried under a 150-kilometer-thick crust of mostly ice."

- NASA Science

These compounds didn't form on the surface. They likely bubbled up from below, carried through cracks and fissures in the ice shell. The presence of these salts suggests active circulation between the ocean and surface, a process that could continuously redistribute nutrients and organic compounds.

Even more intriguing, Juno possibly detected aliphatic aldehydes - organic molecules that on Earth are associated with biological processes. Now, aldehydes can form through non-biological chemistry too, but their presence adds another tantalizing hint that Ganymede's ocean might harbor the chemical complexity life requires.

The ocean's salinity matters for another reason: it depresses the freezing point. Pure water would freeze solid at the temperatures and pressures inside Ganymede. But saltwater can remain liquid across a much wider range of conditions, potentially maintaining a stable ocean for billions of years.

This raises an obvious question: what keeps Ganymede's ocean liquid? After all, at Jupiter's distance from the Sun, temperatures plummet to -160°C on the surface.

The answer lies in tidal heating, though it's subtle compared to the dramatic volcanic eruptions on Jupiter's moon Io. Ganymede orbits Jupiter in a gravitational dance with Europa and Io, locked in a 1:2:4 orbital resonance. Every time Io completes four orbits, Europa completes two, and Ganymede completes one.

This resonance means Jupiter's gravity tugs on Ganymede in a rhythmic pattern, flexing the moon's interior like a stress ball being squeezed and released. That flexing generates heat through friction - not enough to melt the ice shell, but sufficient to maintain liquid water below.

Scientists also point to radiogenic heating - the warmth produced by radioactive decay of elements in Ganymede's rocky core. Over billions of years, this steady internal heat source has likely played a crucial role in sustaining the ocean.

The thickness of the ice shell actually helps. That 150-kilometer frozen blanket acts as insulation, trapping heat inside and preventing the ocean from freezing. It's counterintuitive: more ice above means more liquid water below.

When astrobiologists talk about habitability, they look for three key ingredients: liquid water, chemical nutrients, and an energy source. Ganymede's ocean potentially checks all three boxes.

The water is abundant - more than nine times Earth's total ocean volume. Check.

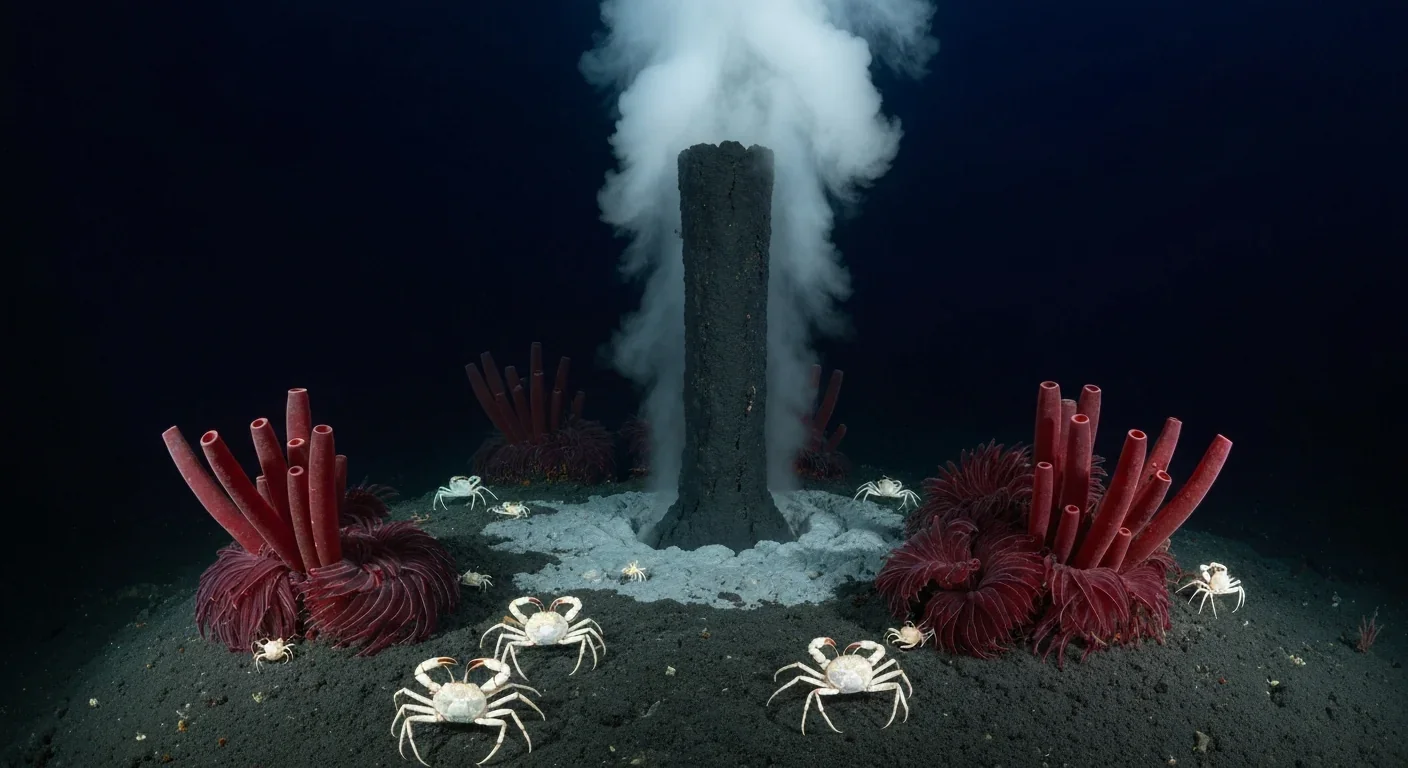

The detection of salts and possible organic compounds suggests chemical complexity. The ocean's contact with the rocky mantle below could enable hydrothermal activity similar to Earth's deep-sea vents, where mineral-rich hot water mixes with cold ocean water. On Earth, these vent systems support entire ecosystems independent of sunlight. Check.

Tidal heating and radiogenic decay provide energy. Not as much as sunlight provides on Earth's surface, but potentially enough to sustain chemical reactions. Check.

Ganymede's ocean has likely existed for billions of years - enough time for life to evolve from simple chemistry to complex organisms, if conditions are right.

There's a fourth factor that often gets overlooked: stability. Ganymede's ocean has likely existed for billions of years. On Earth, life took hundreds of millions of years to evolve from simple chemistry to self-replicating organisms. A long-lived ocean increases the odds that similar processes could occur elsewhere.

That said, challenges remain. The ocean is completely cut off from sunlight, so any life would need to rely on chemosynthesis - deriving energy from chemical reactions rather than photosynthesis. The cold temperatures might slow chemical reactions to a crawl. And the thick ice shell means very limited exchange with the surface, potentially limiting the availability of oxidants that could power metabolism.

But Earth's deep biosphere - the microbes living in rock fractures kilometers below the surface - proves life can thrive in seemingly inhospitable conditions. If life found a way in Earth's deep, dark places, why not Ganymede's?

Here's the brutal truth: we have no current technology capable of reaching Ganymede's ocean.

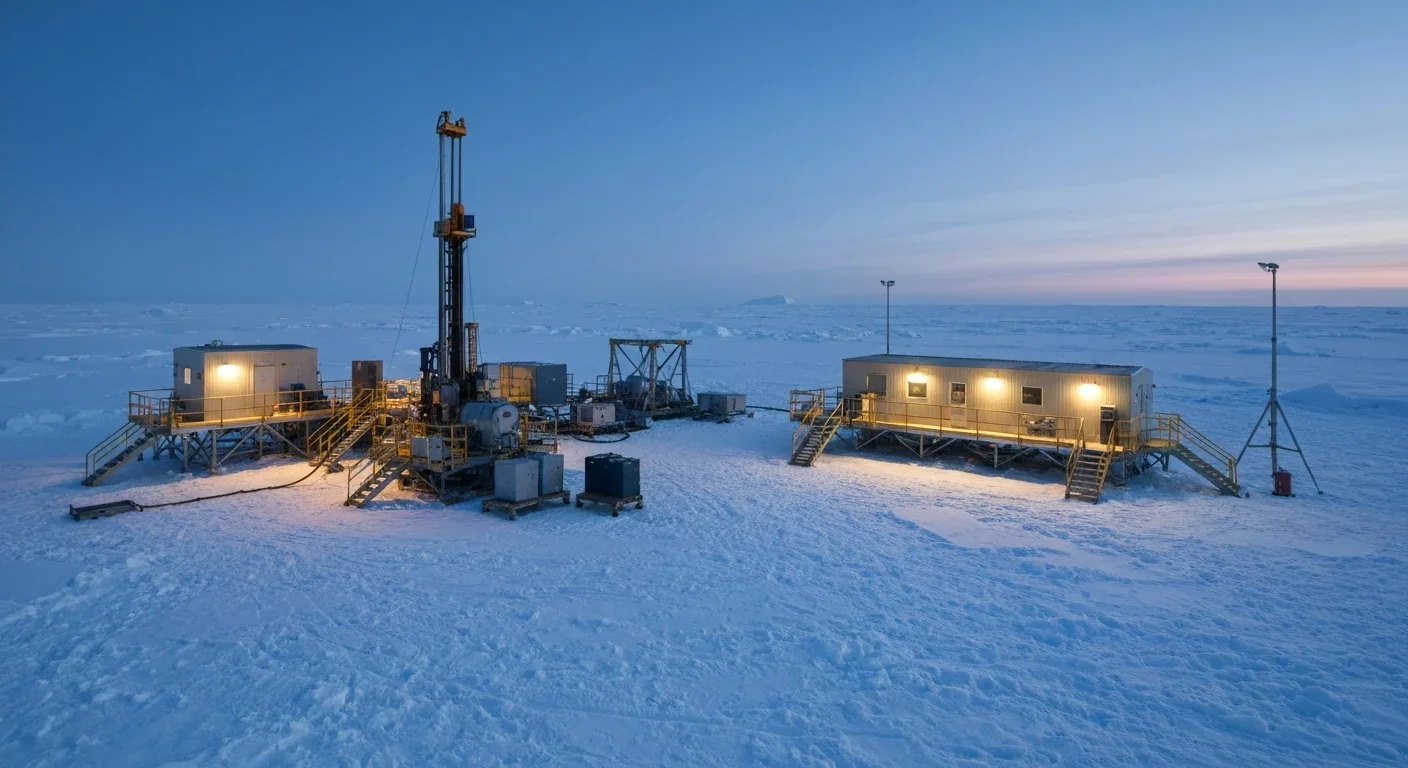

The ice shell is 150 kilometers thick. For perspective, the deepest hole humanity has ever drilled - the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia - reached just 12 kilometers before the heat and pressure became too extreme. And that was on Earth, where we had unlimited power, replacement parts, and engineers on-site.

Drilling through Ganymede's ice would require a mission that could survive the journey to Jupiter (5-7 years), land safely on Ganymede without damaging sensitive equipment, operate autonomously with no real-time control (radio signals take 40+ minutes one way), generate enough power to melt through 150 kilometers of ice, do all of this in temperatures that would freeze most terrestrial equipment solid, and avoid contaminating a potentially habitable environment with Earth microbes.

Several concepts exist. One involves a cryobot - a cylindrical probe that melts its way down through ice using a nuclear heat source. Another proposes using a fleet of small, radiation-hardened robots that work together to establish a drilling outpost.

But these remain firmly in the concept phase. NASA's Europa Clipper mission, launching in 2024, will make detailed studies of Jupiter's icy moons, including Ganymede. The European Space Agency's JUICE mission, arriving in 2034, will spend months orbiting Ganymede, mapping its surface in unprecedented detail and peering through the ice using radar.

These missions won't reach the ocean, but they'll answer crucial questions: How thick is the ice shell really? Does it vary by location? Are there thin spots, cracks, or active plumes that might offer easier access? What exactly is the ocean's chemical composition?

Step back from Ganymede for a moment and consider what this discovery means for the search for life beyond Earth.

For decades, we've focused on the "habitable zone" - that narrow band around a star where temperatures allow liquid water on a planet's surface. But Ganymede exists nowhere near the Sun's habitable zone. It's nearly five times farther from the Sun than Earth is.

Yet it has an ocean. A big one.

This revelation has fundamentally shifted the search for life. Scientists now realize that subsurface oceans might be common throughout the solar system and beyond. Jupiter's moon Europa has one. So does Saturn's moon Enceladus, which actually sprays water from its ocean into space through geysers. Titan might have a subsurface ocean beneath its methane lakes. Even distant Pluto shows evidence of a liquid layer.

"Jupiter's moon Ganymede holds more water than any other object in the solar system."

- Visual Capitalist

If you count all the liquid water in the solar system, Earth holds less than 1%. The rest sloshes around beneath the frozen surfaces of moons we once dismissed as lifeless ice balls.

Exoplanet hunters are taking note. Around other stars, planets don't need to orbit in the narrow habitable zone to potentially harbor life. A planet or moon with sufficient internal heating could maintain a subsurface ocean almost anywhere - around red dwarfs, aging stars, even rogue planets drifting through interstellar space.

This exponentially increases the number of potentially habitable worlds in the universe. We're not just looking for planets like Earth anymore. We're looking for worlds like Ganymede.

Within our lifetimes, robots will swim in Ganymede's ocean. That's not science fiction - it's an engineering problem scientists are actively working to solve.

NASA's Planetary Science Decadal Survey, which sets research priorities for the coming decades, has identified ocean worlds as a top target. The agency is funding research into ice-penetrating robots, autonomous underwater vehicles capable of functioning under ice, and sterilization protocols to ensure we don't contaminate pristine environments.

The JUICE mission represents our first dedicated effort to study Ganymede up close. Arriving in 2034, JUICE will use ice-penetrating radar to create 3D maps of the subsurface, measuring the ocean's depth and potentially detecting variations in salinity and temperature. It'll study the magnetic field in detail, pinpointing where the ocean is closest to the surface.

JUICE's findings will inform future missions. If the spacecraft finds thin spots in the ice, those become prime landing sites. If it detects active geology - cracks that expose fresh ice from below, or areas where ocean water recently reached the surface - those become targets for sample return missions.

Eventually, probably not until the 2040s or 2050s, we'll send a lander equipped with a cryobot. It'll melt through the ice, trailing a fiber-optic cable to relay data back to the surface. Once through, it'll deploy a miniature submarine to explore the dark ocean, searching for signs of life.

Finding life in Ganymede's ocean would be one of humanity's greatest discoveries. But even if we find only sterile water, that tells us something profound: that Earth-like life requires specific conditions that might be rarer than we thought.

There's something deeply humbling about Ganymede's ocean. For millennia, humans looked up at lights in the night sky and wondered if we were alone. We imagined Martians and Moon people. We built telescopes to scan the cosmos for signals from alien civilizations.

All the while, the largest ocean in the solar system - ten times deeper than Earth's, nine times the volume - was hiding in plain sight, orbiting Jupiter in the very sky we'd been studying for centuries.

We just didn't know where to look.

Ganymede isn't a dead rock. It's a world - with an iron core, magnetic field, geological activity, vast liquid ocean, and possibly the chemistry needed for life.

The discovery forces us to reconsider what it means for a world to be "dead." We used to classify moons as inert, frozen rocks - mere gravitational companions to real planets. But Ganymede has an iron core, a magnetic field, geological activity, a vast liquid ocean, and quite possibly the chemistry needed for life.

It's not a dead rock. It's a world.

This semantic shift matters. As we discover more about ocean moons - their geology, their chemistry, their potential for life - we're realizing they deserve the same scientific attention and planetary protection protocols we'd extend to Mars or Venus.

The legal frameworks governing space exploration still refer to "planets and their natural satellites," a distinction that made sense when we thought moons were simple. But Ganymede isn't simple. Neither is Europa, Enceladus, or Titan. They're complex worlds that happen to orbit other worlds.

How we treat these places in the coming decades will set precedents for centuries. Will we approach them with the caution they deserve, careful not to contaminate environments that might harbor life? Or will we rush to exploit their resources - Ganymede's water could theoretically fuel and supply deep-space missions - before we understand what we might destroy?

For now, Ganymede's ocean remains inaccessible, a dark sea beneath an impenetrable frozen ceiling, 628 million kilometers from Earth.

But we know it's there. We've measured its depth, mapped its boundaries, analyzed its chemistry, and confirmed it's been liquid for billions of years. We know it contains more water than every river, lake, and ocean on Earth combined. We know it might - just might - be home to life unlike anything we've encountered.

That knowledge changes everything. It transforms Ganymede from a dot of light in Jupiter's orbit into a destination, a scientific target, a place where humans might one day answer the question that's haunted us since we first looked up at the stars: Are we alone?

The answer might be swimming beneath 150 kilometers of ice, in an ocean deeper and darker than any on Earth, waiting for us to arrive.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

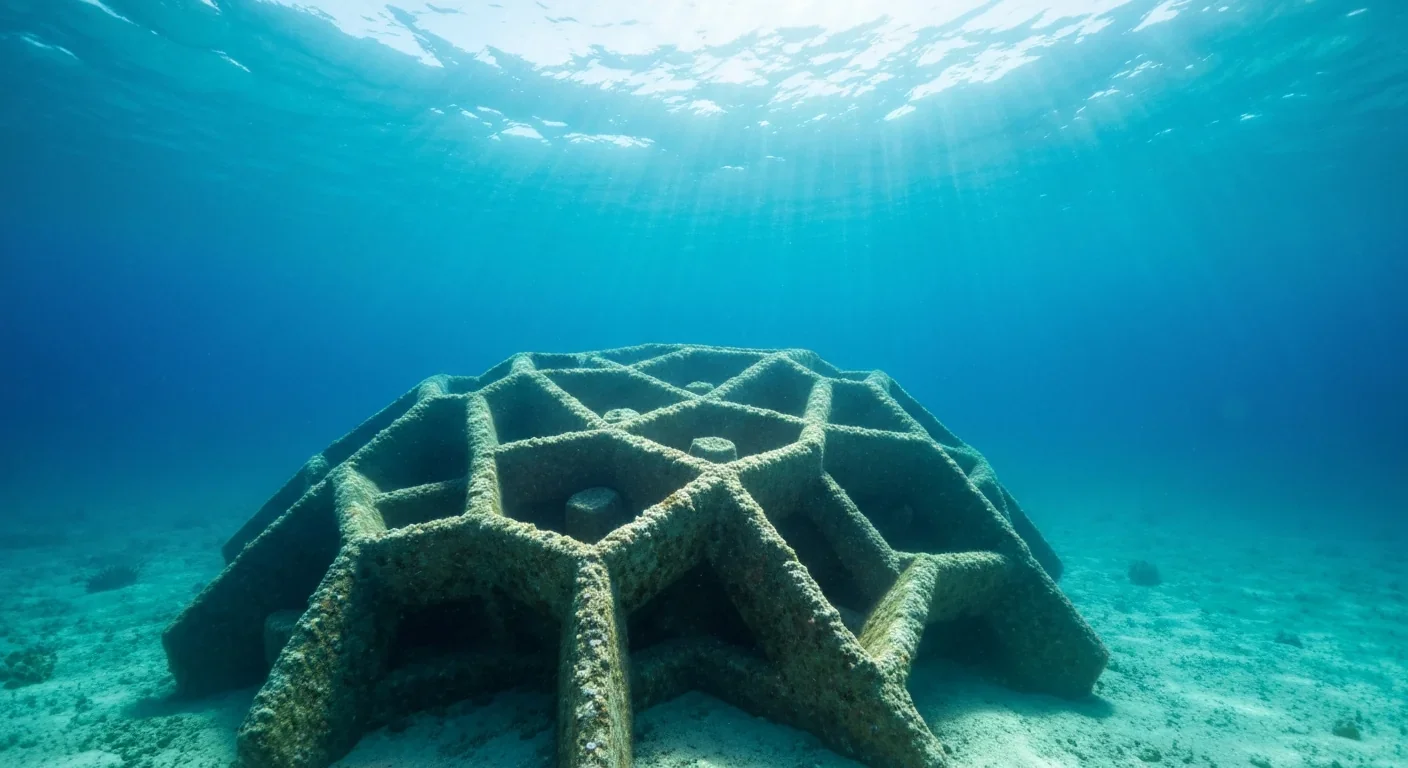

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

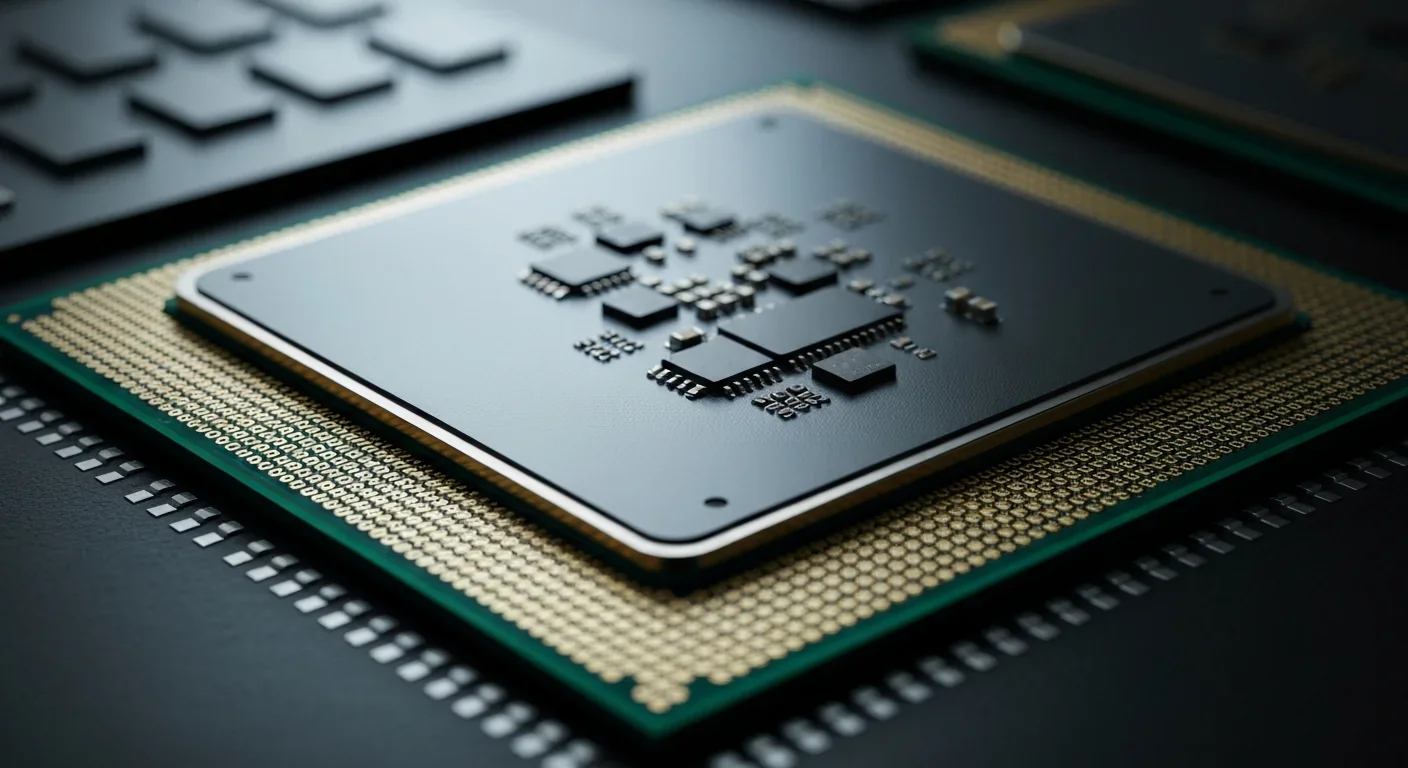

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.