Ice Volcano on Ceres Hints at Hidden Ocean

TL;DR: Magnetars, neutron stars with quadrillion-strength magnetic fields, produce starquakes that release more energy in milliseconds than our Sun emits in 150,000 years. Recent detections link these cosmic earthquakes to Fast Radio Bursts and reveal extreme physics.

Picture a cosmic object the size of Manhattan releasing more energy in a tenth of a second than our Sun will produce in its entire 10-billion-year lifespan. Now imagine that object is a magnetar, a neutron star so magnetically intense it would erase your credit cards from halfway across the solar system. When these stellar remnants experience what astronomers call "starquakes," they unleash gamma-ray bursts that can be detected across the galaxy, briefly outshining everything else in the sky.

These aren't theoretical curiosities. On December 27, 2004, a burst from magnetar SGR 1806-20 hit Earth's upper atmosphere with such force that it temporarily disrupted satellites and ionized our ionosphere from 50,000 light-years away. The event lasted just 0.2 seconds but released approximately 10^46 ergs of energy, making it the brightest explosion ever recorded from beyond our solar system at that time.

Magnetars represent the universe's most extreme magnets. Their magnetic fields reach intensities of 10^15 gauss, roughly a quadrillion times stronger than Earth's modest planetary field. To put that in perspective, if you stood 1,000 kilometers from a magnetar, its magnetic field would be strong enough to disrupt the molecular bonds in your body, essentially pulling you apart at the atomic level.

These cosmic powerhouses form when massive stars, at least 10 to 25 times the Sun's mass, explode as supernovae. The collapsing core compresses into a neutron star just 20 kilometers across but containing more mass than our Sun. During this violent compression, magnetic fields get amplified to incomprehensible strengths through a process called the dynamo effect.

A magnetar's magnetic field is so intense that standing 1,000 kilometers away, it would literally tear your body apart at the molecular level.

Unlike regular neutron stars, which spin hundreds of times per second, magnetars rotate relatively slowly, typically completing one rotation every 2 to 10 seconds. This sluggish spin is a telltale signature: their intense magnetic fields act like cosmic brakes, slowing them down over millennia while simultaneously heating their surfaces to temperatures exceeding 10 million degrees Celsius.

The crust of a magnetar is an extraordinary material, estimated to be a billion times stronger than steel. It consists of a crystalline lattice of atomic nuclei embedded in a sea of electrons, compressed to densities where a teaspoon would weigh as much as Mount Everest. Yet even this super-material has its limits.

Magnetar starquakes occur when internal magnetic stresses overcome the structural integrity of that impossibly strong crust. Think of it like tectonic plates on Earth, but instead of continents drifting millimeters per year, you're dealing with forces that can fracture material billions of times stronger than anything on our planet.

The magnetic field inside a magnetar isn't static. It's constantly evolving, twisting, and reconfiguring. As the star's rotation slows down, the internal magnetic field adjusts, creating mounting pressure on the crust. Eventually, something has to give.

When a starquake strikes, the crust fractures, and the magnetic field lines violently snap and reconnect. This magnetic reconfiguration accelerates particles to near-light speeds, generating an intense burst of X-rays and gamma rays. The initial spike typically lasts just milliseconds, followed by a decaying tail that can persist for minutes.

Remarkably, observations of magnetar XTE J1810-197 in 2018 revealed that a starquake caused the star's surface to become "lumpy" by about one millimeter. This tiny deformation, detected through subtle wobbles in the star's spin, gradually disappeared over three months as the crust settled back into equilibrium. It's astounding: a deviation of just one millimeter on an object 20 kilometers wide can produce observable effects across thousands of light-years.

Detecting magnetar starquakes requires a global network of space-based and ground-based observatories working in concert. The 2004 event from SGR 1806-20 was first picked up by NASA's Swift satellite, triggering alerts to observatories around the world within seconds.

Radio telescopes play a crucial role in magnetar research. When XTE J1810-197 reactivated in December 2018, the University of Manchester's 76-meter Lovell telescope at Jodrell Bank was among the first to detect its radio pulses. The discovery was quickly confirmed by Germany's 100-meter Effelsberg telescope and Australia's 64-meter Parkes telescope, allowing astronomers to track the magnetar's evolution in real-time.

These coordinated observations revealed something unexpected: the normally linearly polarized radio waves were being converted into circularly polarized waves during the outburst. This polarization conversion didn't match theoretical predictions, suggesting that our models of magnetar magnetospheres need refinement.

"The direction of the star's spin was slowly wobbling. By comparing the measured wobble against simulations, we were able to determine the magnetar's surface had become slightly lumpy due to the outburst."

- Radio Astronomy Team, Jodrell Bank Observatory

Modern detection methods also involve monitoring for Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs), mysterious millisecond-duration radio flashes that have puzzled astronomers for years. In April 2020, magnetar SGR 1935+2154 produced an FRB simultaneously with an X-ray burst, providing the first direct evidence that at least some FRBs originate from magnetar activity. This discovery opened a new window into understanding both phenomena.

The April 2020 detection from SGR 1935+2154 marked a turning point in magnetar research. Located roughly 30,000 light-years away in the constellation Vulpecula, this magnetar produced a bright radio burst coincident with X-ray and gamma-ray emission. The simultaneous multi-wavelength detection allowed astronomers to study the physics of magnetic field reconfiguration with unprecedented detail.

What made this event particularly significant was its energy scale. The radio burst was bright enough to be detected across our galaxy, yet it was relatively weak compared to the mysterious extragalactic FRBs. This suggested that magnetar flares could explain nearby FRBs but might require additional mechanisms, like young magnetars in supernova remnants, to account for the most luminous distant bursts.

The 2022 observations added another layer of complexity. Astronomers tracking multiple magnetars found evidence of quasi-periodic oscillations in their X-ray emissions, hinting at seismic waves reverberating through the neutron star's crust after major quakes. These oscillations, with periods of tens to hundreds of milliseconds, provided the first direct probe of a magnetar's interior structure, much like how seismic waves from earthquakes reveal Earth's internal layers.

One particularly intriguing finding emerged from long-term monitoring: a 2024 study suggested that periodic gamma-ray bursts from SGR 1806-20 might be influenced by a planet orbiting the magnetar. This hypothetical world, designated SGR 1806-20 b, would have a mass between 10 and 18 Earth masses and follow a highly eccentric 398-day orbit. If confirmed, it would demonstrate that planetary bodies can survive in the extreme environments around magnetars and might even trigger starquakes through tidal stresses during close approaches.

Magnetar starquakes push our understanding of physics into uncharted territory. The magnetic field strengths involved approach the Schwinger limit, the theoretical threshold at which quantum electrodynamics predicts that empty space itself becomes unstable and begins spontaneously producing particle-antiparticle pairs.

When magnetic field lines snap and reconnect during a starquake, they accelerate electrons and positrons to speeds exceeding 99.9% the speed of light. These ultra-relativistic particles collide with photons, boosting them up to gamma-ray energies through inverse Compton scattering. The resulting cascade produces the brilliant flash we observe as a gamma-ray burst.

The December 2004 magnetar flare released more energy in 0.1 seconds than our Sun will produce in 150,000 years - roughly 10^40 joules in a single eyeblink.

Recent theoretical work has focused on understanding the equation of state of neutron star matter under these extreme conditions. The crust isn't uniform; it consists of layers with different compositions and properties. The outer crust contains conventional atomic nuclei in a crystalline structure, while deeper layers transition into exotic "nuclear pasta," where nuclei merge into rod-like and slab-like structures before dissolving entirely into a superfluid neutron soup.

Research published in 2024 demonstrated that magnetar flares might also play a crucial role in cosmic element synthesis. The intense neutron flux from a major flare can drive rapid neutron capture processes, forging heavy elements like gold, platinum, and uranium. This suggests that in addition to neutron star mergers, magnetar starquakes contribute to the universe's inventory of precious metals.

The energy budget of these events is staggering. The December 2004 flare released about 10^40 joules in one-tenth of a second. For comparison, the total energy output of the Sun over 150,000 years amounts to roughly 1.85 × 10^39 joules. A single magnetar starquake, lasting less time than a human eyeblink, outshines 150 millennia of solar fusion.

Could a magnetar starquake threaten Earth? The short answer is: only if we're extremely unlucky.

The December 2004 event from SGR 1806-20 occurred about 50,000 light-years away, near the far side of our galaxy. Despite that enormous distance, it briefly saturated gamma-ray detectors on multiple satellites and measurably ionized Earth's upper atmosphere. The ionization disrupted radio communications and affected the planet's magnetic field for several minutes.

Scientists have calculated that if a similar giant flare occurred within 10 light-years of Earth, the consequences would be severe. The gamma radiation would strip away a significant portion of our ozone layer, exposing the surface to dangerous ultraviolet radiation and potentially triggering a mass extinction event. The atmospheric damage would be comparable to a 12-kiloton nuclear explosion occurring 7.5 kilometers overhead.

Fortunately, no known magnetars exist within this danger zone. The nearest confirmed magnetar, SGR 0418+5729, lies about 6,500 light-years away. Given that researchers estimate only about 30 million inactive magnetars might exist throughout the Milky Way, and our galaxy spans 100,000 light-years, the odds of a close encounter are reassuringly low.

Still, the 2004 event served as a wake-up call. It demonstrated that magnetar flares can affect our planet from across the galaxy. As we become increasingly dependent on satellite technology for communications, navigation, and Earth monitoring, understanding and predicting magnetar activity becomes a practical concern, not just an academic curiosity.

Despite decades of research, magnetars remain deeply mysterious. One fundamental puzzle is the origin of their extreme magnetic fields. The leading theory invokes a dynamo mechanism during the supernova collapse, where rapid rotation and convection amplify seed fields to magnetar strengths. However, the details remain murky, and alternative models, such as fossil fields inherited from the progenitor star, haven't been ruled out.

"The observed linear-to-circular polarization conversion during the 2018 outburst did not align with theoretical frequency-dependence predictions, indicating more complex plasma processes in the magnetar's magnetosphere."

- Radio Polarization Study Team

Another mystery concerns the trigger mechanism for starquakes. While magnetic stress is clearly involved, we don't understand exactly when or why the crust decides to fracture. Some events seem to occur randomly, while others show patterns suggesting external triggers. The possible planetary companion to SGR 1806-20, if confirmed, would add tidal forces to the mix, potentially explaining the periodicity of some bursts.

The connection between magnetars and Fast Radio Bursts remains incomplete. While the 2020 detection from SGR 1935+2154 proved that magnetars can produce FRBs, many FRB properties, particularly their extreme brightness and repeating patterns, remain unexplained. Some astronomers propose that young magnetars embedded in supernova remnants might amplify their emissions through interactions with surrounding material, but this idea needs observational confirmation.

Looking ahead, next-generation facilities promise to revolutionize magnetar science. The Square Kilometre Array (SKA), currently under construction in Australia and South Africa, will be sensitive enough to detect weak radio pulses from distant magnetars and monitor their long-term evolution. Space-based X-ray observatories like China's Einstein Probe and NASA's proposed STROBE-X mission will catch transient flares with unprecedented timing resolution, revealing the detailed physics of magnetic reconnection.

Theoretical advances are equally important. Supercomputer simulations are now approaching the scales needed to model neutron star interiors and magnetospheres from first principles. These simulations combine general relativity, quantum chromodynamics, and plasma physics to recreate the extreme conditions inside and around magnetars. The next decade should bring a convergence of observation and theory, finally answering some of the most fundamental questions about these enigmatic objects.

Magnetars occupy a unique place in the cosmic ecosystem. They form from only the most massive stars, those destined to die as supernovae rather than fading quietly like our Sun. This means they trace the history of star formation and stellar death across cosmic time.

Because magnetars remain active for only about 10,000 years before their magnetic fields decay, any magnetar we observe today formed relatively recently in astronomical terms. The population of active magnetars thus provides a snapshot of recent supernova activity in our galactic neighborhood.

Intriguingly, the extreme magnetic fields of magnetars might make them laboratories for testing fundamental physics. Quantum electrodynamics, the theory describing the interaction between light and matter, has been verified to extraordinary precision in laboratory conditions. But magnetar environments represent a regime billions of times more extreme. Observations of magnetar emission could reveal subtle deviations from standard QED predictions, hinting at new physics beyond the Standard Model.

The energy released by magnetar starquakes also feeds back into the interstellar medium. The expanding shells of hot gas and relativistic particles from giant flares can trigger star formation in nearby molecular clouds, accelerate cosmic rays, and enrich the galaxy with heavy elements. In this sense, magnetars aren't isolated objects but active participants in galactic evolution.

Every magnetar starquake offers a glimpse into physics at the absolute edge of what's possible in our universe. These events involve matter compressed to nuclear densities, magnetic fields approaching quantum limits, and energy releases that dwarf anything achievable on Earth.

When astronomers detected that December 2004 burst, they witnessed a cosmic phenomenon that occurred 50,000 years ago, when Homo sapiens were just beginning to spread beyond Africa. The gamma rays traveled across the galaxy while our species invented agriculture, built civilizations, and developed the technology to detect their arrival.

The study of magnetar starquakes bridges multiple frontiers: astrophysics, nuclear physics, plasma physics, and general relativity all intersect in these extraordinary objects. As our instruments grow more sensitive and our theories more sophisticated, we're learning to read the signals from these cosmic earthquakes, decoding messages about the fundamental nature of matter and energy under conditions we can barely imagine, let alone replicate.

In the grand scheme of cosmic violence, magnetar starquakes stand in a league of their own. They're not as energetic as supernovae or black hole mergers, but they pack an incomparable punch per unit volume. A Manhattan-sized object releasing more energy in a fraction of a second than our life-giving Sun produces in geological epochs, that's the kind of extreme event that reminds us how much we still have to learn about the universe.

And somewhere out there, right now, another magnetar's crust is accumulating stress. Magnetic forces are building toward the breaking point. When it finally cracks, the resulting flash will race across the galaxy at the speed of light, perhaps arriving at Earth decades or centuries from now. When it does, our descendants' instruments will be waiting, ready to capture another fleeting glimpse of nature at its most extreme.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

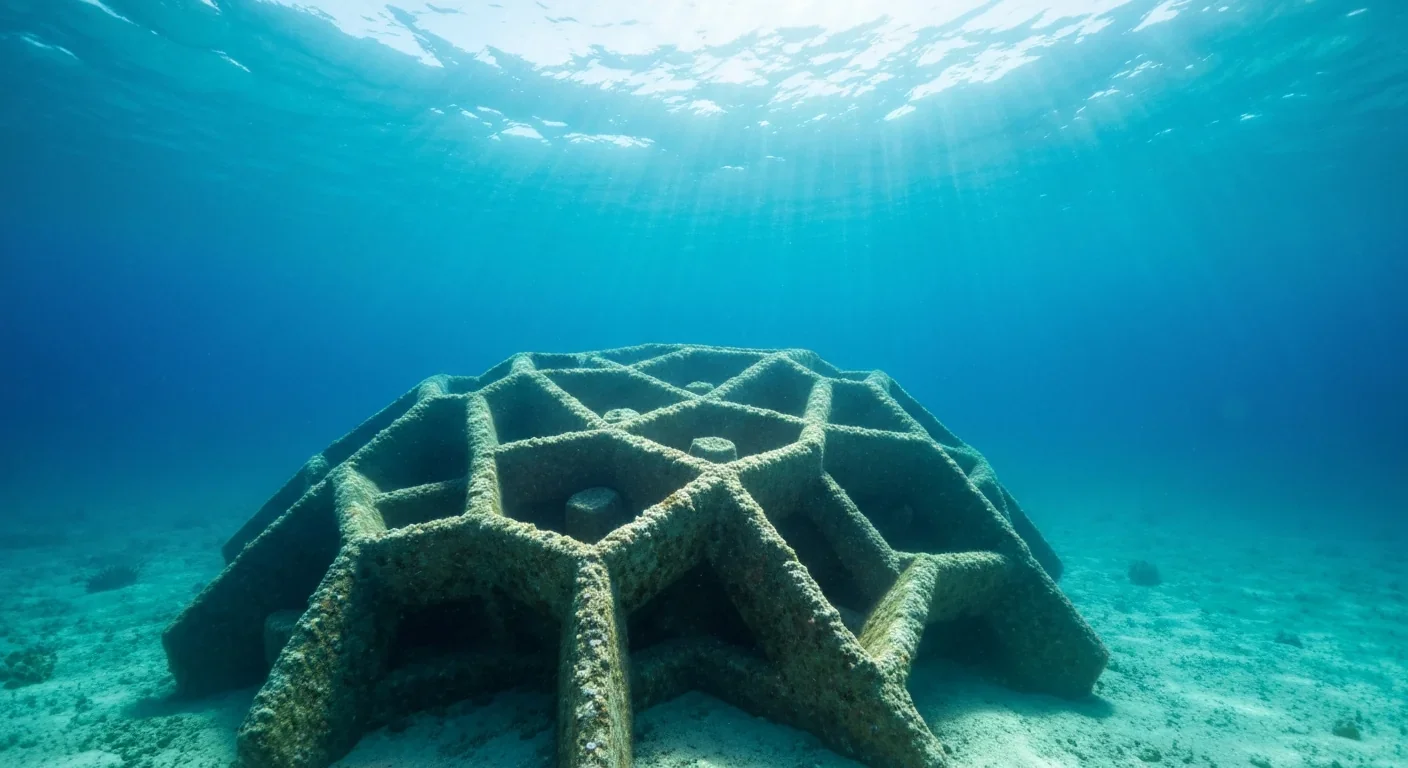

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

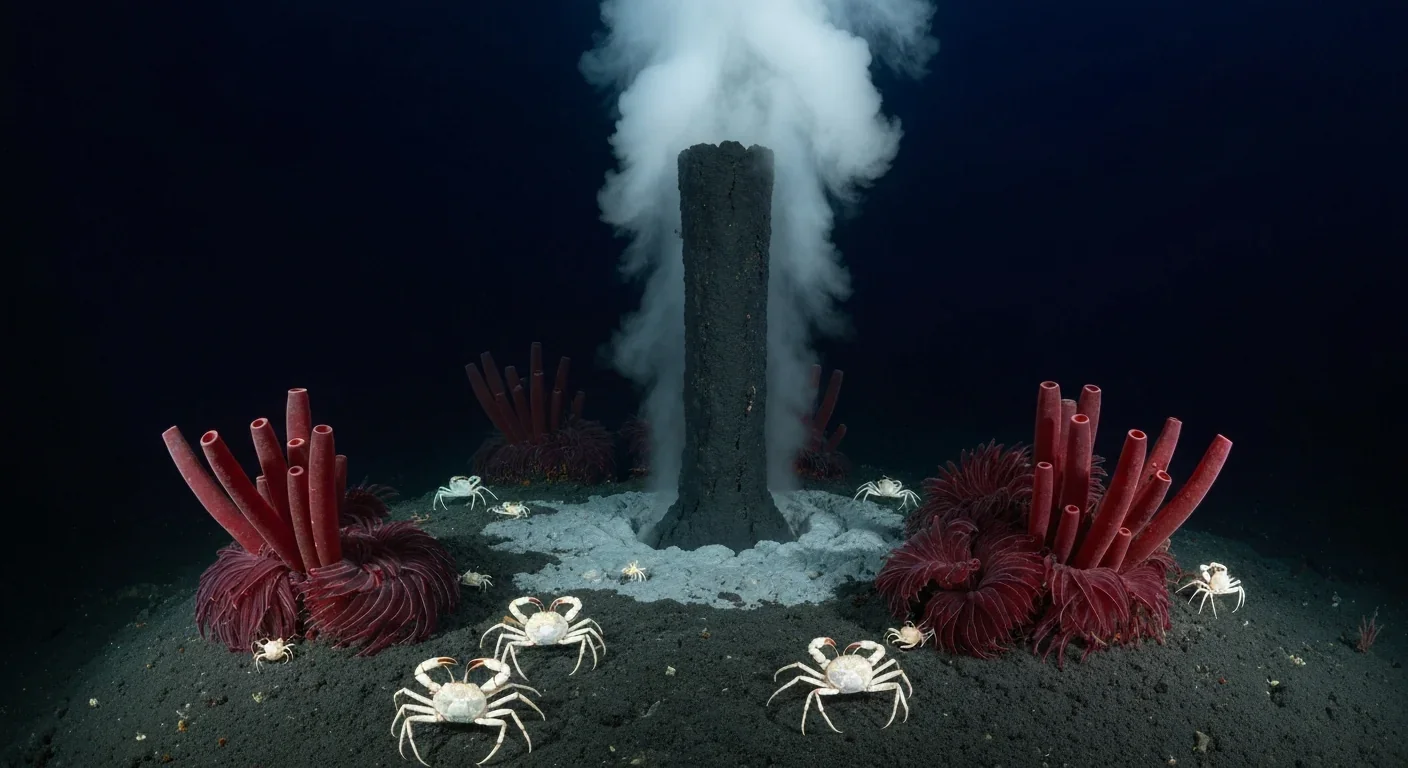

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

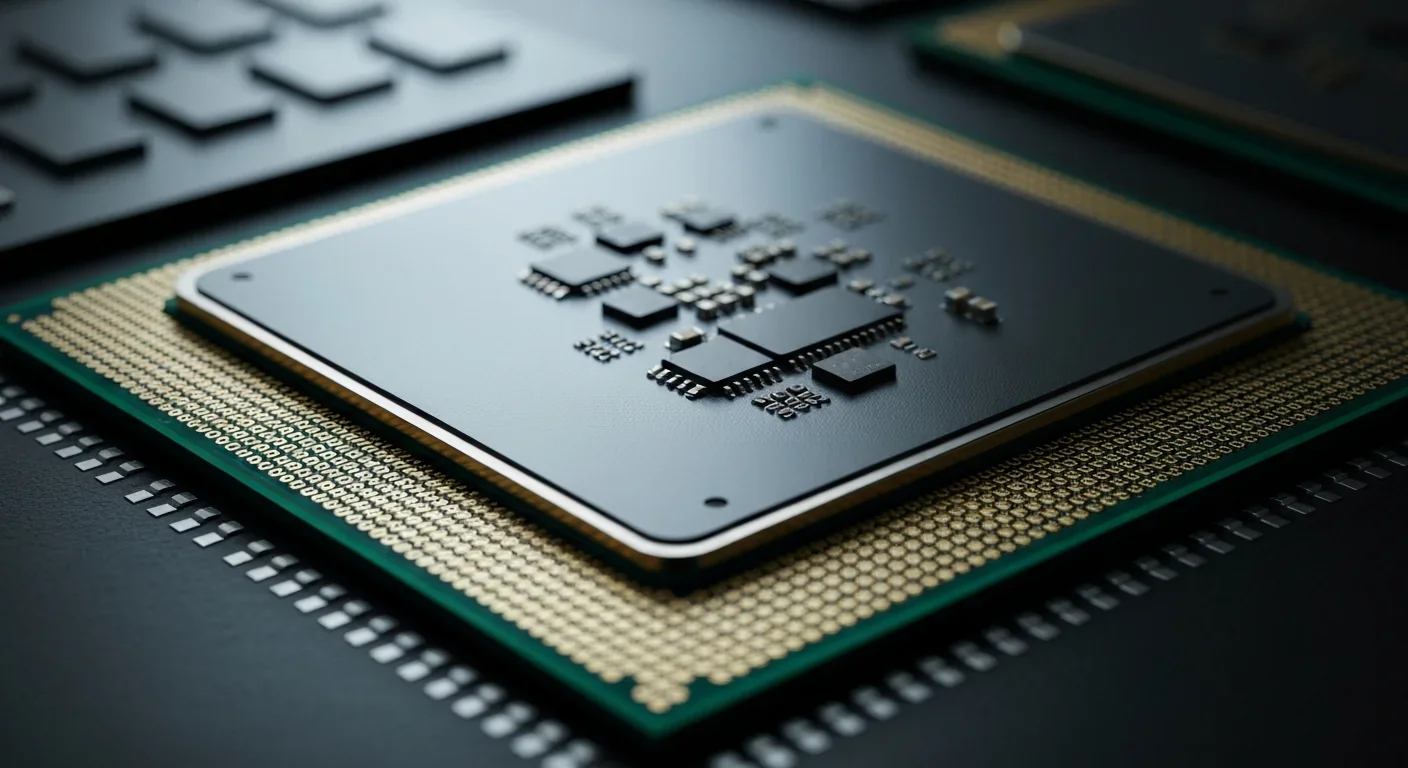

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.