Ice Volcano on Ceres Hints at Hidden Ocean

TL;DR: Scientists can now sample an alien ocean by flying spacecraft through Enceladus's 500km-tall geysers. Cassini discovered organic molecules, salts, and chemical energy sources in these plumes, but detecting actual life requires next-generation instruments that can distinguish biological from non-biological chemistry at extreme speeds.

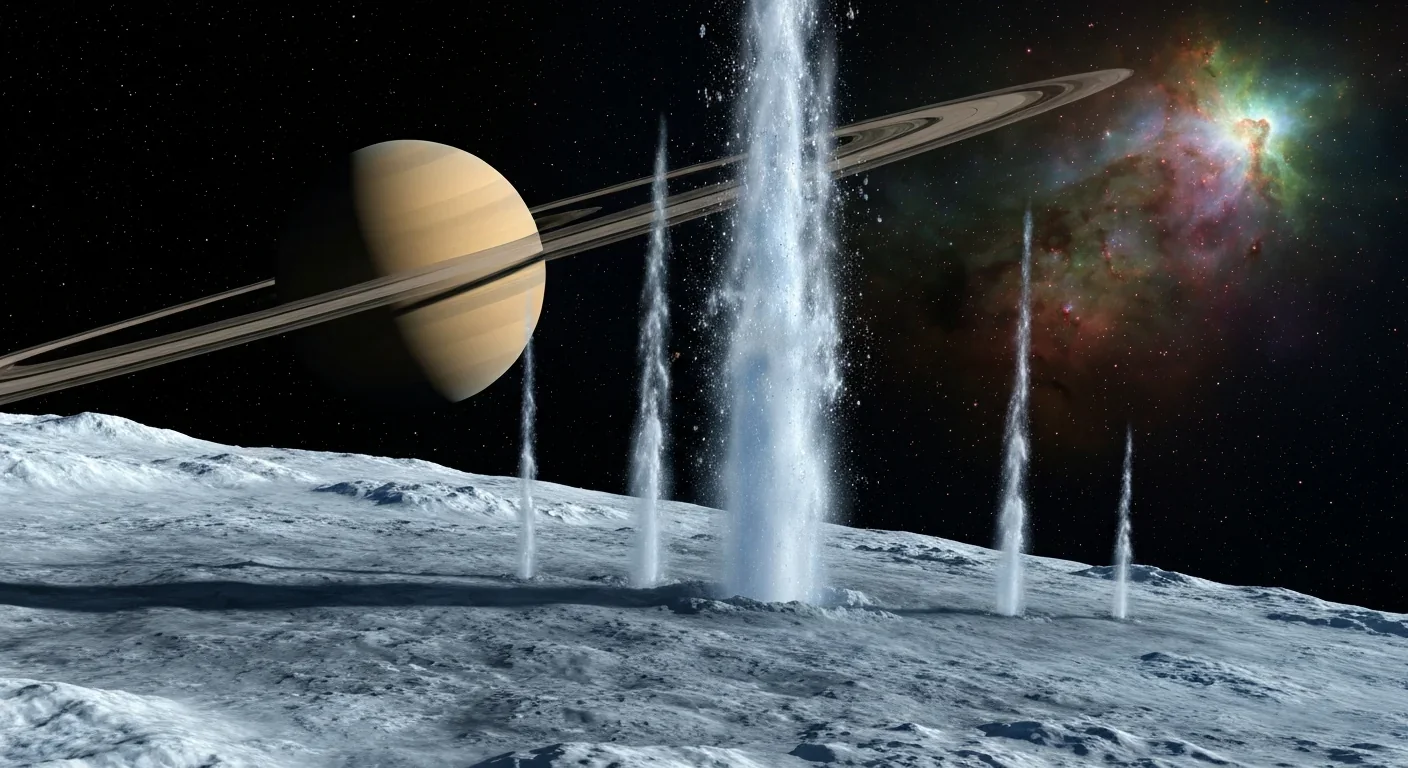

Right now, scientists have a direct pipeline to an alien ocean, and they didn't need to land a spacecraft or drill through miles of ice to get it. Saturn's moon Enceladus is literally spewing the contents of its subsurface ocean into space through towering geysers that reach 500 kilometers high. For the first time in history, we can sample an extraterrestrial ocean by simply flying through the spray.

Between 2005 and 2015, NASA's Cassini spacecraft completed 22 daring flybys through these plumes, swooping as close as 25 kilometers above the surface. What it found has reshaped our understanding of where life might exist beyond Earth. The plumes contain complex organic molecules, salts with an ocean-like composition, and chemical energy sources that could theoretically support microbial life.

But collecting samples while flying through a geyser at several kilometers per second is far from simple. The technical challenges are staggering, the risk of contamination is real, and distinguishing between biological and non-biological chemistry in these extreme conditions requires instruments that can analyze molecules in fractions of a second.

This is the story of how we're hunting for alien life in one of the solar system's most promising locations, and why the next generation of missions might finally answer the question that has captivated humanity for millennia.

Before 2005, searching for life beyond Earth meant thinking about landing on Mars or drilling through Europa's thick ice shell. Then Cassini discovered something that fundamentally changed the game. Geyser-like plumes of water vapor and ice grains were continuously erupting from cracks in Enceladus's icy surface, particularly from four parallel fractures scientists dubbed "tiger stripes."

These aren't gentle wisps. The plumes dispense 250 kilograms of water vapor every second at speeds reaching 2,189 kilometers per hour. Over 100 individual geysers have been identified in the tiger stripe regions, and together they create a massive plume system that feeds material into Saturn's E-ring.

What makes this discovery transformative is what the plumes represent: a natural sampling mechanism. The water vapor and ice grains come from a global ocean estimated to be 26 to 31 kilometers deep beneath the ice shell. Unlike Europa or Mars, where we'd need to land and drill, Enceladus brings its ocean to us.

Dr. Morgan Cable from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory: "Enceladus is the only confirmed body in the solar system where we have access to fresh material from a habitable subsurface ocean."

The implications rippled through the astrobiology community. If we could analyze these plumes properly, we could study an alien ocean's chemistry without the enormous cost and complexity of a lander mission. But that "if" contains a universe of technical challenges.

Imagine trying to catch raindrops while driving at highway speeds, except the raindrops are ice grains traveling at 400 to 800 meters per second, you're in a spacecraft moving at several kilometers per second in the opposite direction, and you need to identify specific molecules in those grains before they vaporize.

That's essentially what Cassini's Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer had to accomplish. The sampling process began with high-velocity impacts between the spacecraft and solid plume particles. These collisions, happening at closing speeds that could exceed 10 kilometers per second, instantly broke up the ice grains into smaller, charged fragments.

The fragmentation isn't a problem; it's the solution. The instrument then used an electric field to accelerate these ionized fragments toward a detector. By measuring how long each fragment took to reach the detector, the spectrometer could calculate mass-to-charge ratios and identify the molecules present.

This time-of-flight mass spectrometry allowed Cassini to detect molecular masses up to 200 atomic mass units, capturing everything from simple water molecules to complex organic compounds. But the entire analysis had to happen in milliseconds, during the brief window when the spacecraft was passing through the plume.

The challenge wasn't just speed. At such high velocities, there's a real risk of destroying the very molecules you're trying to detect. Delicate organic compounds can break apart on impact, and biological molecules are particularly fragile. This creates a fundamental tension: you need high-speed impacts to ionize and fragment the samples for analysis, but not so violent that you obliterate potential biosignatures.

Engineers designing future missions are working on this problem. Some proposed instruments use gentler capture mechanisms, while others rely on improved mass spectrometry that can detect even degraded biosignatures. The Mass Spectrometer for Planetary EXploration, or MASPEX, represents the next generation with significantly enhanced sensitivity and resolution.

MASPEX can achieve mass resolution exceeding 30,000 M/dM and analyze more than 5,000 samples per second. Its extended mass range above 1,000 daltons means it can detect larger organic molecules that might indicate biological processes. Most importantly, its enhanced sensitivity reaches better than one part per trillion when using cryotrapping, allowing it to identify trace amounts of potential biosignatures.

The chemistry Cassini discovered in those fleeting encounters is remarkable. The plumes aren't just water; they're a complex cocktail that tells us about conditions in the ocean below.

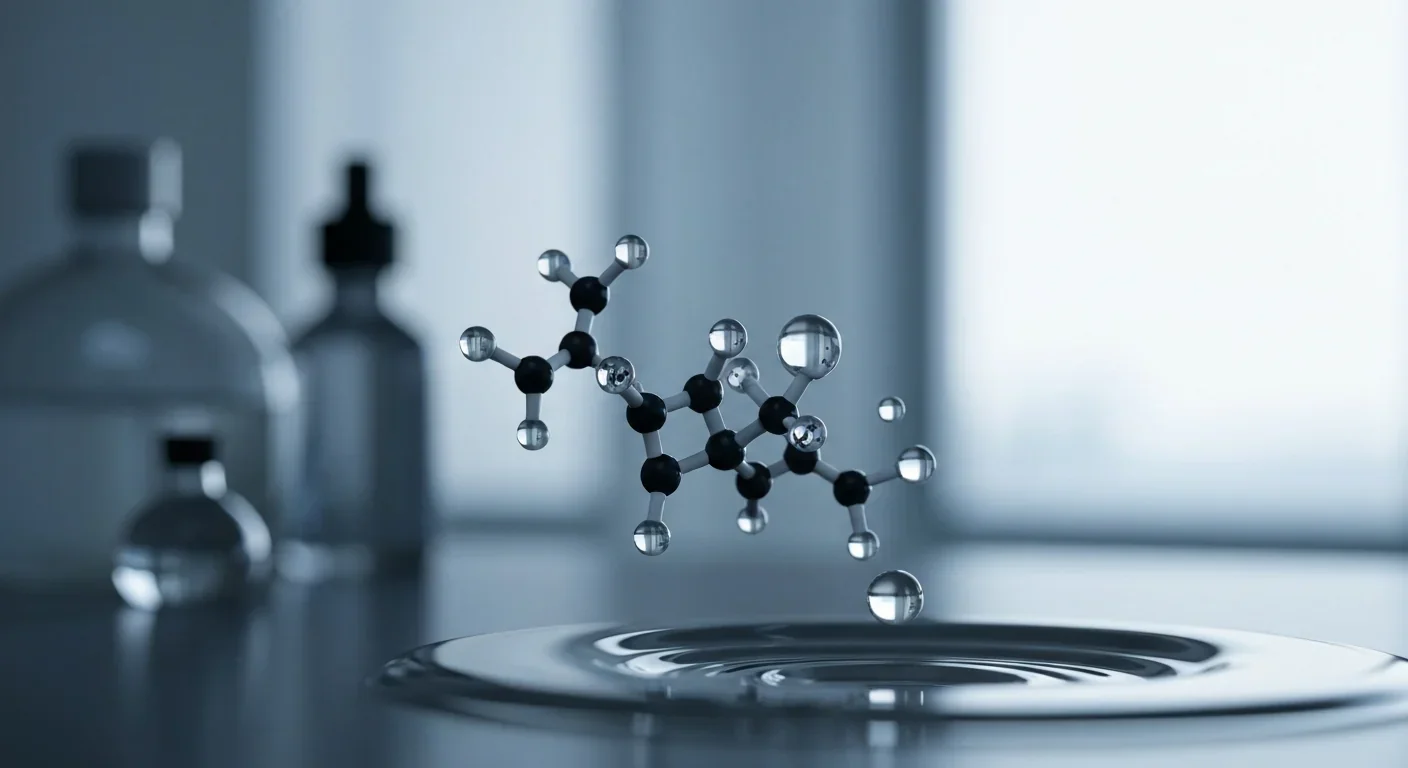

Organic molecules detected include methane, propane, acetylene, and formaldehyde. More intriguing are the amines, which are precursors to amino acids, which in turn can form proteins. Even larger macromolecules have been observed, suggesting chemical complexity that approaches the threshold of biological relevance.

A 2025 reanalysis of Cassini data found evidence of previously undetected organic compounds in fresh ice grains collected just 21 kilometers above Enceladus's surface. Lead researcher Nozair Khawaja explained that these organics were "just minutes old, found in ice that was fresh from the ocean below Enceladus's surface."

"The freshness of these samples matters enormously. What we detected represents the ocean's actual chemistry, not artifacts created by space weathering."

- Nozair Khawaja, Free University of Berlin

The freshness matters enormously. Older ice grains that have spent years in Saturn's E-ring get bombarded by radiation, which can create or destroy organic molecules. By sampling fresh plume material during fast flybys, scientists guaranteed removal of any interference from radiation alteration. What they detected represents the ocean's actual chemistry, not artifacts created by space weathering.

The plumes also contain salts with an ocean-like composition and silica nanoparticles indicating interaction with a rocky substrate. These silica particles are particularly interesting because they suggest water is reacting with rock at the ocean floor, potentially at hydrothermal vents.

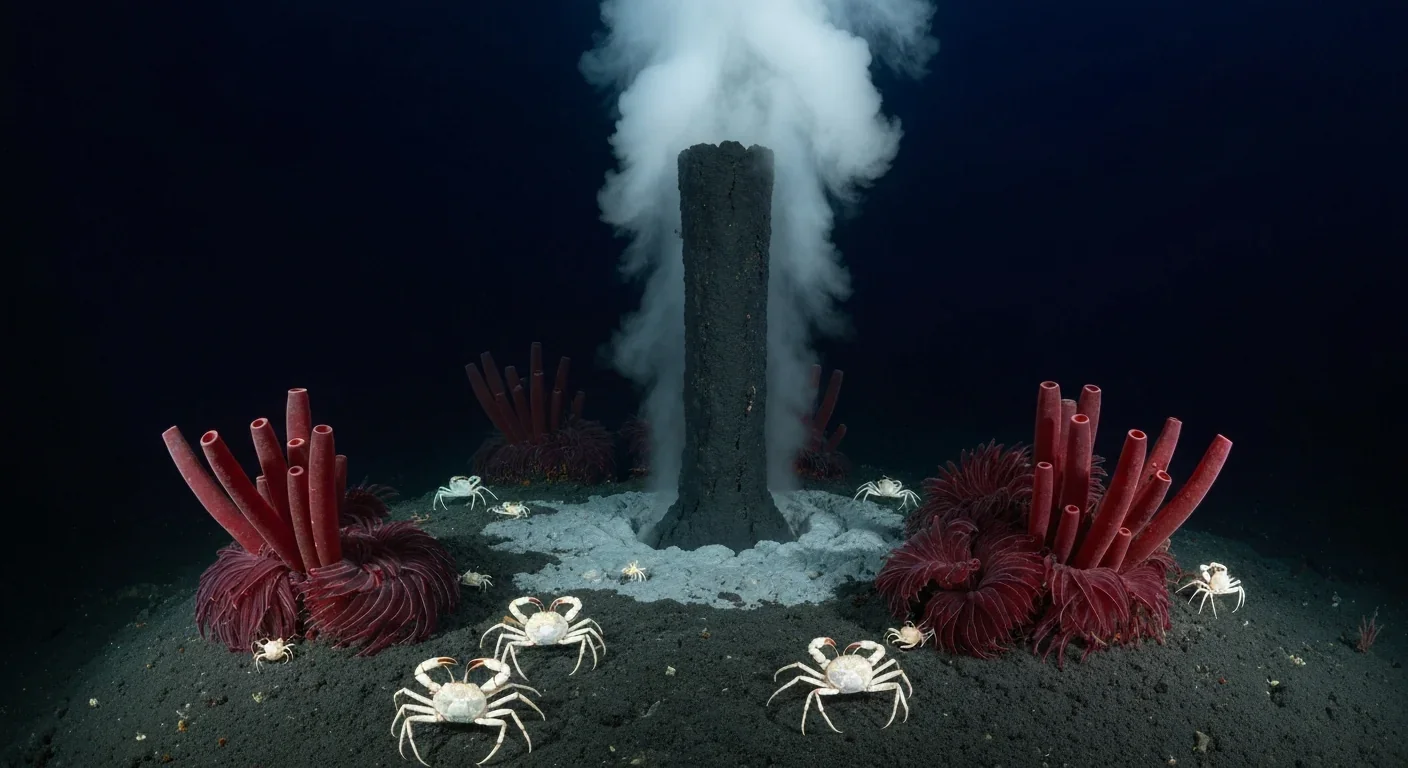

Perhaps most exciting is the hydrogen. The amount detected is so large that it requires a present-day source within Enceladus's ocean, most likely hydrothermal vents. On Earth, hydrogen from hydrothermal vents provides chemical energy for ecosystems that thrive in complete darkness, independent of sunlight. If similar chemosynthetic pathways operate on Enceladus, the ingredients for life are available in sufficient quantities.

But here's where it gets complicated. A recent study using large-scale chemical equilibrium modeling suggests that silica nanoparticles would dissolve within months in Enceladus's ocean conditions, and ocean circulation would take over a century to transport them from hydrothermal vents to the surface. This implies the silicon detected might instead form near the ice-ocean interface, similar to particles at marine ice-ocean interfaces on Earth.

The ambiguity underscores a critical point: interpreting plume chemistry isn't straightforward. The same molecules can have biological or non-biological origins, and transport processes can alter what we detect. This is why multiple lines of evidence are essential.

Finding organic molecules in space isn't rare. We've detected them in comets, asteroids, and interstellar clouds. The challenge is distinguishing between organic chemistry and biochemistry, between molecules that formed through ordinary chemical processes and those that were produced by living organisms.

This is where biosignatures come in. Rather than looking for life directly, scientists search for chemical or physical signatures that would be difficult to produce without biological processes. On Enceladus, several potential biosignatures are being considered.

Molecular complexity and chirality are strong indicators. Life on Earth uses only left-handed amino acids and right-handed sugars, a preference called homochirality. If plume samples showed a similar imbalance, particularly in large, complex organic molecules, that would be difficult to explain through non-biological processes alone.

Isotopic ratios provide another diagnostic. Biological processes often favor lighter isotopes. A new technique using Orbitrap mass spectrometry can determine nitrogen isotope ratios in picomole quantities with high precision. If Enceladus's organics show isotopic fractionation consistent with biological processing, that would strengthen the case for life.

Macromolecular patterns matter too. Life produces polymers like proteins, DNA, and lipids with specific structures and repeating units. Recent work by Fabian Klenner from the University of Washington showed that mass spectrometry can detect even a single bacterial cell embedded in an ice grain.

Modern instruments can identify biomolecules such as lipids, polypeptides, DNA or RNA in plume particles. Dr. Cable explained that next-generation detectors could confirm the presence of life "even if there is a single alien microbe entrained within an ice grain in the plume."

Next-generation instruments can now detect individual microbial cells in plume samples, potentially confirming life with a single flyby.

Direct detection of cells is now technically feasible. Digital holographic microscopy can detect active motion and morphological features at concentrations as low as 100 cells per milliliter. Active motion is particularly compelling because it's hard to explain through non-biological processes. A future mission equipped with such instruments could capture video of swimming microorganisms in plume samples.

The challenge is getting enough material. Recent studies suggest that missions may need to collect 100 times more material than previously estimated to adequately characterize the ocean's chemistry, particularly its salt content and trace organics. This has major implications for mission design.

Finding organics in Enceladus's plumes would be meaningless if those organics came from Earth. Contamination control is perhaps the most critical, and most underappreciated, aspect of life detection missions.

Enceladus is classified as a Category III target under international planetary protection protocols. This designation requires trajectory biasing, clean room assembly, bioburden reduction, and a complete inventory of organic compounds on the spacecraft. These aren't suggestions; they're requirements enforced by treaty.

The rationale is twofold. First, we must avoid forward contamination, where Earth microbes could colonize Enceladus and compromise its pristine environment. Second, we need to ensure that any biosignatures we detect genuinely come from Enceladus, not from contamination carried by the spacecraft.

NASA's experience with the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission illustrates how critical this is. Senior sample scientist Danny Glavin noted that "the clues we're looking for are so minuscule and so easily destroyed or altered from exposure to Earth's environment." The mission required meticulous contamination control measures and careful curation to preserve fragile biosignatures.

For Enceladus missions, contamination challenges multiply. The spacecraft must be assembled in clean rooms to minimize biological contamination. Every surface must be cataloged for organic compounds so scientists can distinguish spacecraft-derived molecules from Enceladean ones. The instruments that collect samples must be pristine, sealed until needed, and operated in ways that prevent cross-contamination.

There's also the issue of sample preservation. Any detected biosignatures must remain stable during the analysis process. High-speed impacts generate heat, which can alter or destroy delicate molecules. Radiation exposure during the journey from Enceladus to the instrument can break chemical bonds. Even the ionization process used for mass spectrometry can fragment fragile organic compounds.

Future missions are exploring various solutions. Some designs include cryogenic sample storage to preserve molecules in their original state. Others use protective shielding to reduce radiation exposure. Still others rely on redundant analysis methods, so if one technique destroys the sample, others can confirm the findings.

The planetary protection framework isn't just about preventing contamination; it's about maintaining scientific credibility. A single contamination event could invalidate an entire mission's findings and set back our search for life by decades.

Cassini wasn't designed to find life. Its mass spectrometer had limited sensitivity and resolution by today's standards. It couldn't detect isotopic ratios or distinguish between left-handed and right-handed molecules. Yet what it accomplished fundamentally transformed astrobiology.

The mission confirmed that Enceladus has all the basic ingredients for life as we know it: liquid water, organic compounds, and chemical energy sources. It showed that the ocean is in contact with a rocky core, enabling water-rock reactions that produce the chemistry needed for life. It demonstrated that this chemistry is being continuously delivered to the surface, where we can sample it.

Perhaps more importantly, Cassini proved that flyby sampling works. The 22 close encounters, conducted over a decade, provided statistical confidence that what was detected genuinely represents Enceladus's composition. Repeated observations showed the plume chemistry is consistent over time, ruling out transient contamination or measurement errors.

The mission also revealed the limitations of current technology. Cassini detected organic molecules but couldn't determine their specific structures or whether they formed through biological processes. It found hydrogen but couldn't confirm the presence of hydrothermal vents. It collected material from a potentially habitable ocean but couldn't answer whether anything actually lives there.

"Cassini proved that flyby sampling works. Now we know what questions to ask and what instruments we need to answer them."

- Astrobiology Mission Planning Team

These limitations define the agenda for future missions. We now know what questions to ask and what instruments we need to answer them. The next generation of missions to Enceladus will benefit enormously from Cassini's pathfinding work.

While Enceladus grabs headlines, Jupiter's moon Europa faces similar challenges and offers similar opportunities. Like Enceladus, Europa has a subsurface ocean beneath an icy crust. Like Enceladus, it appears to vent material into space, though Europa's plumes are more sporadic and less well-characterized.

NASA's Europa Clipper mission, launching in 2024, will use many of the same sampling techniques pioneered at Enceladus. The spacecraft will make dozens of close flybys through any plumes it detects, using advanced mass spectrometers to analyze their composition.

Europa Clipper's Mass Spectrometer for Planetary EXploration represents a significant leap in capability compared to Cassini's instruments. With its enhanced mass resolution of over 30,000 and sensitivity down to parts per trillion, MASPEX can detect and identify complex organic compounds that would have been invisible to earlier instruments.

The mission will also carry the Surface Dust Analyzer, designed to capture larger particles and analyze their composition without complete vaporization. This dual approach, collecting both gas-phase and solid samples, provides complementary data that could resolve ambiguities in molecular identification.

Europa Clipper won't definitively answer whether Europa hosts life, but it will determine whether the moon has the conditions necessary for habitability. If it detects compelling biosignatures, it will set the stage for a follow-up mission, possibly a lander that could conduct more detailed analyses.

The parallels between Europa and Enceladus mean that discoveries at one moon inform our understanding of the other. Techniques developed for Europa Clipper could be adapted for future Enceladus missions, and vice versa. Both moons represent what scientists call "ocean worlds," a class of bodies that may be among the most common habitable environments in the galaxy.

The European Space Agency is planning an Enceladus mission launching in the 2040s that will perform multiple flybys and possibly orbit the moon. Unlike Cassini, this mission would be purpose-built for life detection, carrying instruments specifically designed to identify biosignatures.

Several mission concepts are in development. The Enceladus Life Finder would focus exclusively on detecting amino acids and determining their chirality. The Enceladus Orbilander proposes a two-stage mission: an orbiter that maps the plumes and identifies the best sampling locations, followed by a lander that could conduct long-term studies of surface ice.

These future missions face a fundamental trade-off between flybys and orbital missions. Flybys allow sampling of fresh plume material with minimal radiation alteration, but they provide limited observation time and require high-speed collection. Orbiters can make repeated passes and optimize sampling conditions, but they accumulate radiation damage that complicates contamination control.

Future Enceladus missions face a critical challenge: they may need to collect 100 times more material than originally planned to definitively characterize the ocean's chemistry and search for life.

Landing on Enceladus would enable the most detailed studies, but it comes with enormous challenges. The tiger stripe regions where the plumes originate are geologically active and potentially dangerous. Landing in these areas risks the spacecraft being damaged by erupting geysers. Landing elsewhere means analyzing older ice that may not represent current ocean chemistry.

There's also the problem of scale. Even with better instruments, we may need to collect far more material than flybys typically provide to definitively characterize the ocean's chemistry and search for life. Some proposed missions include sample return components, bringing Enceladus ice back to Earth for analysis in sophisticated laboratories.

The timeline is frustratingly long. ESA's mission won't launch until the 2040s, and it would take nearly another decade to reach Saturn. We're looking at the 2050s before we might get definitive answers about life on Enceladus. This has led some scientists to advocate for faster, smaller missions that could provide interim results and guide the design of more ambitious efforts.

Private space companies are beginning to show interest in outer solar system missions, potentially accelerating the timeline. However, the technical challenges, planetary protection requirements, and sheer distances involved make Enceladus missions inherently expensive and complex.

Imagine it's 2052, and a purpose-built Enceladus life-detection mission has completed its analysis. What would constitute proof of life?

The answer is complex because biology doesn't conveniently label itself. There's no single "smoking gun" that would provide absolute certainty. Instead, scientists are looking for multiple, independent lines of evidence that collectively make the biological explanation far more plausible than any non-biological alternative.

Finding organic molecules with strong homochirality, particularly in amino acids, would be compelling evidence. Life on Earth shows near-perfect selectivity for left-handed amino acids, and achieving this through random chemistry is statistically improbable. If Enceladus showed similar selectivity, especially in a diverse range of amino acids, that would be very difficult to explain without biology.

Detecting intact cells or cellular structures would be even more convincing. Modern instruments can potentially identify individual microbial cells based on their morphology, biochemical composition, and active motion. Finding lipid membranes, nucleic acids, or proteins in patterns consistent with cellular organization would build a strong case.

Isotopic signatures could provide crucial supporting evidence. Biological nitrogen isotope fractionation, detected through high-precision mass spectrometry, would suggest metabolic processes at work. Carbon isotope ratios showing biological preference for lighter isotopes would add further weight.

The presence of biological polymers with specific sequences or patterns would be transformative. DNA or DNA-like molecules with coding sequences, proteins with functional domains, or polysaccharides with regular structures all point toward biology.

But even with all these lines of evidence, certainty will be difficult. Life on Enceladus, if it exists, might not resemble Earth life. It could use different biochemistry, different molecules, or different organizational principles. Our biosignature search strategies are necessarily Earth-centric because that's the only example we have.

This is why multiple missions, using different techniques and targeting different aspects of the question, will likely be necessary before we can say with confidence whether Enceladus harbors life.

The question of life on Enceladus extends far beyond one small moon. The techniques being developed for plume sampling, the instruments being designed for biosignature detection, and the contamination control protocols being refined will shape how we search for life throughout the solar system and beyond.

Ocean worlds appear to be common. Beyond Enceladus and Europa, evidence suggests subsurface oceans on Titan, Ganymede, Callisto, and possibly even distant Pluto. If we confirm life on Enceladus, it would suggest that habitable environments are far more widespread than we imagined.

The implications for the origin of life would be profound. If life arose independently in Enceladus's ocean, it would suggest that the emergence of life is relatively easy when the right conditions exist. This would dramatically increase the probability of finding life elsewhere in the universe.

Alternatively, if Enceladus's ocean proves to have the ingredients for life but no actual organisms, that would tell us something equally important: that having the right chemistry isn't enough, and some additional factor or process is required for life to begin.

The way we're studying Enceladus also provides a template for exploring exoplanets. We can't visit planets around other stars, but we can study their atmospheres for biosignatures. The same principles we're developing for distinguishing biological from non-biological chemistry will apply when we analyze the atmospheric composition of Earth-like planets light-years away.

There's a broader cultural impact too. The search for life beyond Earth captures public imagination in ways few scientific endeavors can match. Every discovery at Enceladus, every new piece of evidence about its ocean and chemistry, reminds us that we live in a solar system where multiple worlds might harbor life. It challenges our conception of Earth as special and hints at a universe that may be teeming with biology we've yet to discover.

The hunt for life on Enceladus represents one of humanity's most audacious scientific quests. We're attempting to answer a question that philosophers and scientists have pondered for millennia: Are we alone?

Every flyby through Enceladus's plumes brings us closer to an answer. The organic molecules Cassini detected, the chemical energy sources, the global ocean, the apparent hydrothermal activity - each discovery narrows the possibilities and sharpens our questions.

The technology is advancing rapidly. Instruments that seemed impossible a decade ago are now being built and tested. Mass spectrometers with unprecedented sensitivity, microscopes that can detect individual cells, contamination control systems that can distinguish Earth organics from alien ones - the tools we need are becoming real.

The missions are being designed. Engineers are solving the technical challenges of high-speed sampling, figuring out how to collect enough material, developing ways to preserve fragile molecules, and planning trajectories that will optimize scientific return.

Yet for all this progress, we're still in the early stages. Cassini proved that Enceladus is worth studying. Europa Clipper will test new techniques at Jupiter. The ESA mission in the 2040s might provide the definitive answer. But even if that mission detects compelling evidence of life, there will be calls for confirmation, for additional missions, for sample return.

The search for life is not a sprint; it's a generational endeavor that will likely continue throughout this century and beyond. But that's appropriate for a question this profound. Finding life on Enceladus wouldn't just be a scientific discovery; it would fundamentally reshape our understanding of our place in the universe.

So we'll keep flying through those towering geysers, collecting their spray, analyzing their chemistry molecule by molecule. We'll keep refining our instruments, improving our techniques, and asking more sophisticated questions. Because somewhere in those plumes, in the ice grains ejected from an alien ocean beneath miles of ice around a distant world, might be the answer we've been seeking since we first looked up at the stars and wondered if anyone was looking back.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

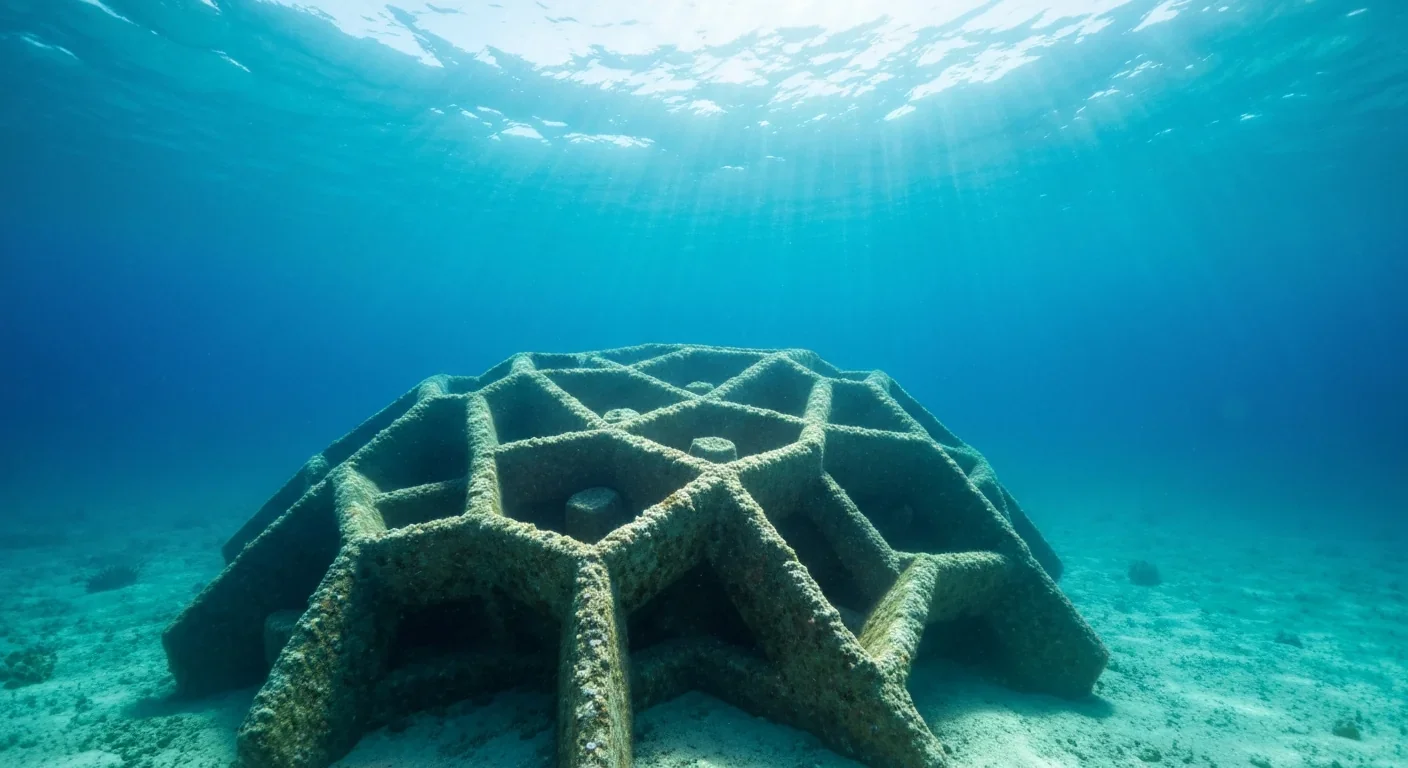

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.