Ice Volcano on Ceres Hints at Hidden Ocean

TL;DR: Quaoar's ring system defies physics by existing well beyond the Roche limit where rings should collapse into moons. Discovered in 2023, these impossible rings challenge fundamental planetary science theories and may reshape our understanding of ring systems throughout the universe.

In the frigid darkness beyond Neptune, a dwarf planet called Quaoar is quietly demolishing one of astronomy's most trusted rules. Its rings shouldn't exist. They can't exist. The physics are clear, the math is settled, and yet there they are, orbiting serenely at a distance where gravity should have torn them apart millions of years ago. When astronomers discovered Quaoar's ring system in 2023, they didn't just find another cosmic ornament. They stumbled onto evidence that our understanding of how rings form and survive might be fundamentally incomplete.

The discovery represents more than an astronomical curiosity. It's a reminder that even in our own solar system, barely four billion miles from Earth, nature still keeps secrets that challenge our most basic assumptions about how worlds work.

The story begins with a technique astronomers have used for decades: stellar occultation. When a distant object passes in front of a star from our perspective, the starlight dims in revealing ways. It's like watching someone's shadow cross a wall, you can deduce their shape even if you can't see them directly. In February 2023, ground-based telescopes tracked Quaoar as it drifted across a background star. Instead of one clean dimming event, they detected multiple brief flickers before and after the main occultation.

Those flickers were rings. Two of them.

The initial observations from Earth's surface were remarkable enough, but the real shock came when researchers pointed the James Webb Space Telescope at a similar occultation event later that year. JWST's infrared capabilities provided unprecedented detail, revealing that the outer ring, designated Q1R, orbits at approximately 4,100 kilometers from Quaoar's center, while the inner ring, Q2R, sits even farther out. Both rings appeared narrow, dense, and utterly impossible according to the standard model of ring formation.

Both rings orbit well beyond Quaoar's Roche limit, the boundary where planetary gravity should overwhelm particle cohesion and prevent ring formation. Discovering stable rings here is like finding water flowing uphill.

The problem? Both rings orbit well beyond Quaoar's Roche limit, the boundary where a planet's gravity should overwhelm the self-gravity holding ring particles together. Beyond this limit, particles should clump together and form moons, not maintain stable rings. It's a rule that has held true for every other ring system we've studied, from Saturn's majestic bands to the wispy rings around Neptune.

Discovering rings beyond the Roche limit is like finding water flowing uphill. The laws of physics haven't changed, so something else must be going on.

To understand why Quaoar's rings are so baffling, you need to grasp what the Roche limit actually represents. Named after French astronomer Édouard Roche, who calculated it in 1848, this boundary marks the distance at which tidal forces from a planet become stronger than the gravitational forces holding a smaller body together.

Imagine you're a small moon orbiting close to a massive planet. The side of you facing the planet experiences stronger gravity than your far side because it's closer to the gravitational source. This difference, the tidal force, tries to stretch you apart. Your own internal gravity fights back, trying to keep you whole. Close enough to the planet, tidal forces win, and you disintegrate into a ring of debris.

For a rigid, rocky body, the Roche limit sits at about 2.5 times the planet's radius. For looser, rubble-pile structures, it's closer to 3 times the radius. Inside this boundary, rings thrive. Material can't coalesce into moons because tidal forces shred any attempted assembly. Outside this boundary, particles should gradually stick together through collisions and electrostatic forces, eventually forming moons.

Saturn's rings, the solar system's most spectacular example, all orbit well within Saturn's Roche limit. The same goes for Jupiter's rings, Uranus's rings, and Neptune's rings. Every major ring system discovered around planets has obeyed this fundamental rule.

Until Quaoar.

Quaoar's rings orbit at distances roughly 7 to 7.5 times the dwarf planet's radius. That puts them nearly three times farther out than the Roche limit. At that distance, conventional tidal theory predicts the rings should have collapsed into a moon within a few decades at most, probably much faster.

Yet there they are, apparently stable, showing no signs of imminent collapse.

The JWST observations added more puzzling details. The rings aren't made of tiny dust particles like some tenuous ring systems. Analysis of how they blocked starlight at different wavelengths suggests the particles are at least 3 to 4 meters in diameter, maybe larger. These aren't specks clinging together by static electricity. They're substantial chunks that should have long ago gravitationally attracted each other and merged.

"The optical depth measurements show values around 0.01 to 0.07 in the densest regions. That's not sparse dust. It's a real ring with meaningful mass distributed across it."

- JWST Research Team, Observatoire de Paris

Temperature estimates from the JWST data revealed another intriguing detail. The ring particles appear extremely cold, below 44 Kelvin (about -380°F). At those temperatures, water ice becomes harder than steel, and methane ice behaves like rock. This has implications for how the particles interact and how easily they might stick together during collisions.

If physics says these rings should collapse, but they haven't, then something must be actively preventing that collapse. Astronomers focused their attention on Quaoar's known moon, Weywot.

Weywot orbits Quaoar at a distance of about 14,500 kilometers, roughly three times farther out than the outer ring. It's a small moon, perhaps 80 kilometers across, but its gravitational influence extends inward toward the rings. More importantly, Weywot's orbit is in resonance with both rings.

Orbital resonances occur when two orbiting bodies exert regular, periodic gravitational tugs on each other. The classic example is Jupiter's influence on the asteroid belt, where gaps appear at specific distances corresponding to resonances. A 2:1 resonance means an asteroid completes exactly two orbits for every one Jupiter completes, creating a repeating pattern of gravitational nudges that eventually ejects the asteroid from that region.

Analysis suggests Quaoar's outer ring sits near a 6:1 mean-motion resonance with Weywot. For every six orbits the ring particles complete, Weywot completes one. The inner ring appears to be at a 7:5 resonance. These aren't random alignments. Resonances can confine and stabilize orbits in counterintuitive ways.

Think of it like pushing a child on a swing. If you push randomly, nothing much happens. But push in rhythm with the swing's natural motion, and small nudges accumulate into large effects. Weywot might be "pushing" the ring particles in just the right rhythm to keep them spread out and prevent them from clumping together.

But there's a problem with this explanation: Weywot is tiny. Its gravitational influence is weak. Can such a small moon really maintain rings across such a large distance? The math gets fuzzy. Some models suggest it's possible, especially if the ring particles are larger and fewer in number, reducing the collision rate that would normally lead to aggregation. Other models aren't so sure.

Recent observations have added another twist. Some astronomers now suspect Quaoar might have a second, undiscovered moon. During detailed analysis of occultation data, researchers noticed additional brief dimming events that don't match the known rings or Weywot's position. These could be instrumental artifacts, but they could also be a small, previously undetected satellite.

If a second moon exists, particularly one orbiting between or near the rings, it could provide the additional gravitational sculpting needed to maintain ring stability. Small "shepherd moons" famously keep some of Saturn's rings confined, with moons on either side of a ring preventing particles from spreading out or collapsing inward.

The hunt for this hypothetical second moon continues. Confirming its existence would go a long way toward explaining the rings' persistence, but it wouldn't fully resolve the fundamental question: why can stable rings exist this far beyond the Roche limit in the first place?

Another explanation focuses on the extreme conditions in the outer solar system. At Quaoar's distance from the Sun, about 43 times Earth's distance, temperatures plummet to levels we rarely encounter in the inner solar system. The ring particles aren't just cold, they're approaching what physicists call "brittle ice" conditions.

Laboratory experiments have shown that ultra-cold ice doesn't behave like regular ice. It doesn't stick together easily when pieces collide at low speeds. Instead, collisions tend to bounce or shatter rather than merge. This is counterintuitive because we're used to thinking of ice as sticky, but that stickiness depends on having a thin liquid layer on the surface, something that doesn't exist at 44 Kelvin.

If Quaoar's ring particles are too cold to stick together efficiently, collisions won't lead to aggregation. Particles might bounce off each other for millions of years without ever accumulating into larger bodies. This could effectively extend the timescale for ring collapse from decades to geological epochs.

At 44 Kelvin (-380°F), water ice becomes harder than steel and loses its sticky properties. Ring particles at these temperatures may simply bounce off each other rather than clumping together, defying expectations based on warmer ring systems.

Recent studies have also examined how solar radiation pressure affects small particles this far from the Sun. Even though sunlight is faint at Quaoar's distance, it still exerts a tiny but persistent force on ring particles. For the smallest particles, this force might be enough to counteract the slow inward spiral that would normally occur due to collisions and drag forces. Larger particles, immune to radiation pressure, could remain stable through sheer inertia and the spacing enforced by resonances.

Quaoar's anomalous rings force us to reconsider ring formation and stability across the solar system. If rings can exist beyond the Roche limit under certain conditions, we might be missing rings around other bodies. Observational bias has historically favored finding rings close to planets, where they're brightest and most obvious. Distant, tenuous rings are harder to detect.

The discovery also has implications for exoplanets. As our telescopes improve, we're beginning to detect hints of ring systems around planets orbiting other stars. If we're using Roche limit calculations to predict where rings should appear, we might be looking in the wrong places. Some exoplanets could have extensive ring systems far from their surfaces that we've dismissed as impossible.

There's also a historical parallel worth noting. When Cassini discovered gaps in Saturn's rings in the 1600s, astronomers eventually realized those gaps were maintained by resonances with Saturn's moons. The discovery of shepherd moons in the 1980s further refined our understanding. Quaoar might be teaching us that resonance dynamics can work over much larger distances and in weaker gravitational fields than we previously thought.

Quaoar itself presents another complication: it's not spherical. Like many objects in the Kuiper Belt, Quaoar appears somewhat elongated, possibly with a triaxial ellipsoid shape. This affects how we calculate the Roche limit.

The standard Roche limit formula assumes a spherical parent body with uniform density. Deviations from sphericity create non-uniform gravitational fields. Particles orbiting an elongated body experience varying gravitational tugs depending on their position relative to the body's long and short axes. Recent theoretical work on rings around irregular bodies suggests these variations can create stable zones beyond the classical Roche limit, especially when combined with resonances.

Think of it like orbital potholes. A perfectly smooth gravitational field might not trap particles at large distances, but a lumpy, irregular field creates spots where particles can get gravitationally "caught" and held in place by a combination of the parent body's gravity and resonant effects from distant moons.

This doesn't fully explain Quaoar's rings because the irregularity isn't extreme, but it might be a contributing factor. Combined with Weywot's resonances, cold particle physics, and possibly an undiscovered second moon, the irregular gravity field could tip the balance from "rings should collapse" to "rings can persist."

Quaoar sits in the Kuiper Belt, that vast region of icy bodies beyond Neptune. It's a place we've only begun to explore in detail. The more we look, the stranger things get.

Haumea, another dwarf planet in the Kuiper Belt, also has rings. They were discovered in 2017, also through stellar occultation, and they also orbit beyond Haumea's Roche limit, though not as dramatically as Quaoar's. Chariklo, a small body between Saturn and Uranus, has two dense rings that initially baffled astronomers for similar reasons.

A pattern is emerging. Small, icy bodies in the outer solar system appear more likely to have anomalous ring systems than our Roche limit calculations would predict. This suggests we're missing something fundamental about how rings behave in these extreme cold, low-gravity environments.

"The Kuiper Belt might be teaching us that ring dynamics are more complex and diverse than the neat theories we built studying gas giants in the inner solar system."

- Dr. Bruno Morgado, Lead Researcher, Observatoire de Paris

The Kuiper Belt might be teaching us that ring dynamics are more complex and diverse than the neat theories we built studying gas giants in the inner solar system. Saturn's rings, for all their grandeur, might represent just one way rings can exist, optimized for warm, massive planets. Out in the frozen dark, different rules might apply.

Astronomers are now planning follow-up observations. More occultation events could refine the rings' exact positions and densities. Higher-resolution imaging might finally confirm or rule out a second moon. Laboratory experiments simulating ultra-cold ice collisions could test whether brittle ice physics really can prevent particle aggregation at the observed temperatures.

There's also the possibility of sending a spacecraft, though that's a distant prospect. Even with optimistic mission planning, a probe to Quaoar wouldn't arrive for decades. The dwarf planet orbits so far from the Sun that it takes 288 Earth years to complete one orbit. Catching it at a convenient alignment for a spacecraft trajectory is a rare event.

In the meantime, theoretical work continues. Researchers are developing more sophisticated models that incorporate multiple effects simultaneously: resonances, irregular gravity fields, temperature-dependent collision outcomes, and radiation pressure. These models are computationally intensive, requiring simulations that track thousands of individual particles over millions of orbits.

Early results suggest that under the right combination of factors, stable rings beyond the Roche limit aren't just possible but might even be common in certain environments. The key is finding the right balance: cold enough to prevent sticking, resonant enough to prevent collapse, and massive enough (in the parent body) to maintain some gravitational organization, but not so massive that tidal forces dominate.

Perhaps the most important lesson from Quaoar's rings is a reminder of humility. We've been studying ring systems since Galileo first glimpsed Saturn's "handles" in 1610. We've sent spacecraft to all four gas giants. We've developed sophisticated mathematical models of orbital dynamics and tidal forces. And yet, a frozen world barely one-tenth the diameter of Earth is showing us we still have fundamental gaps in our understanding.

Science progresses not through confirming what we already believe, but through confronting observations that don't fit our theories. Quaoar's rings are doing exactly that. They're forcing planetary scientists to revisit assumptions, test new ideas, and expand the boundaries of what we consider possible.

The dwarf planet sits in the twilight realm of the solar system, so distant that sunlight takes more than six hours to reach it. From Quaoar's surface, the Sun would appear as just another bright star, offering no warmth. It's a place of profound cold and darkness, seemingly alien to our experience. Yet the physics operating there are the same physics that govern Earth's orbit and the fall of an apple from a tree.

Or so we thought.

The discovery of Quaoar's rings opens new research directions across multiple fields. Planetary scientists will need to develop ring formation models that account for conditions beyond the classical assumptions. Observational astronomers will look for similar ring systems around other trans-Neptunian objects, potentially discovering that Quaoar isn't unique but rather representative of a whole class of ringed worlds we've been overlooking.

Exoplanet researchers will reconsider how they search for rings around distant worlds. If rings can exist far from their parent bodies under the right conditions, detection strategies might need adjustment. The transit method, which detects planets by watching them pass in front of their stars, could reveal ring systems that extend much farther than current models predict.

There's also a materials science angle. Understanding how ultra-cold ice behaves during collisions has implications beyond astronomy. Engineers working on cryogenic systems, researchers studying comets, and even those investigating the icy moons of the outer planets could benefit from better models of ice physics at extreme temperatures.

The rings might also tell us about Quaoar's history. Did they form from a recent collision that shattered a small moon? Are they primordial remnants from Quaoar's formation 4.6 billion years ago? The answer would inform our understanding of how the Kuiper Belt evolved and how common collisional events are in that distant region.

Quaoar, named after a creation deity from the Native American Tongva people of Southern California, seems to be living up to its name by creating new puzzles for astronomers to solve. Its rings challenge our textbook understanding of planetary systems, suggesting that the universe still has surprises waiting in the cold, dark corners of our own cosmic neighborhood.

The dwarf planet's gift to science isn't just the rings themselves, it's the questions they raise. Why do they exist? What's keeping them stable? What else have we gotten wrong about how small bodies behave in the outer solar system? Each question leads to others, creating a cascade of inquiry that drives science forward.

In the end, Quaoar reminds us that exploration isn't just about traveling to distant places. Sometimes the most profound discoveries come from looking more carefully at places we thought we already understood. The outer solar system, long considered a frozen graveyard of primordial leftovers, is turning out to be a dynamic laboratory where the rules of planetary science are still being written.

As telescopes improve and observation techniques advance, we'll continue to probe Quaoar's secrets. Each new data point brings us closer to understanding not just this particular system, but the fundamental principles governing how worlds form, evolve, and maintain their ornaments across the cosmic depths. The frozen world is teaching us that in science, as in exploration, the most important discoveries often come from things that shouldn't exist but do.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

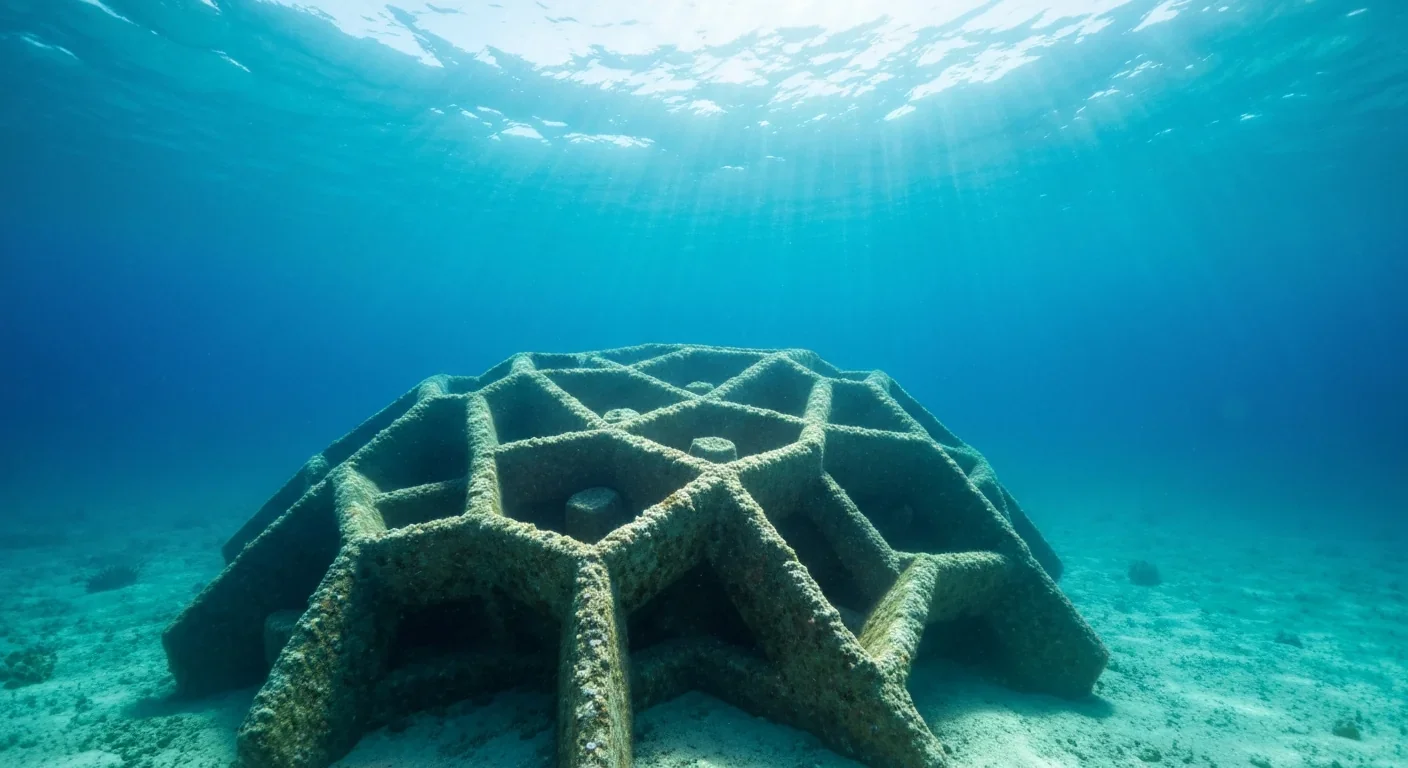

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

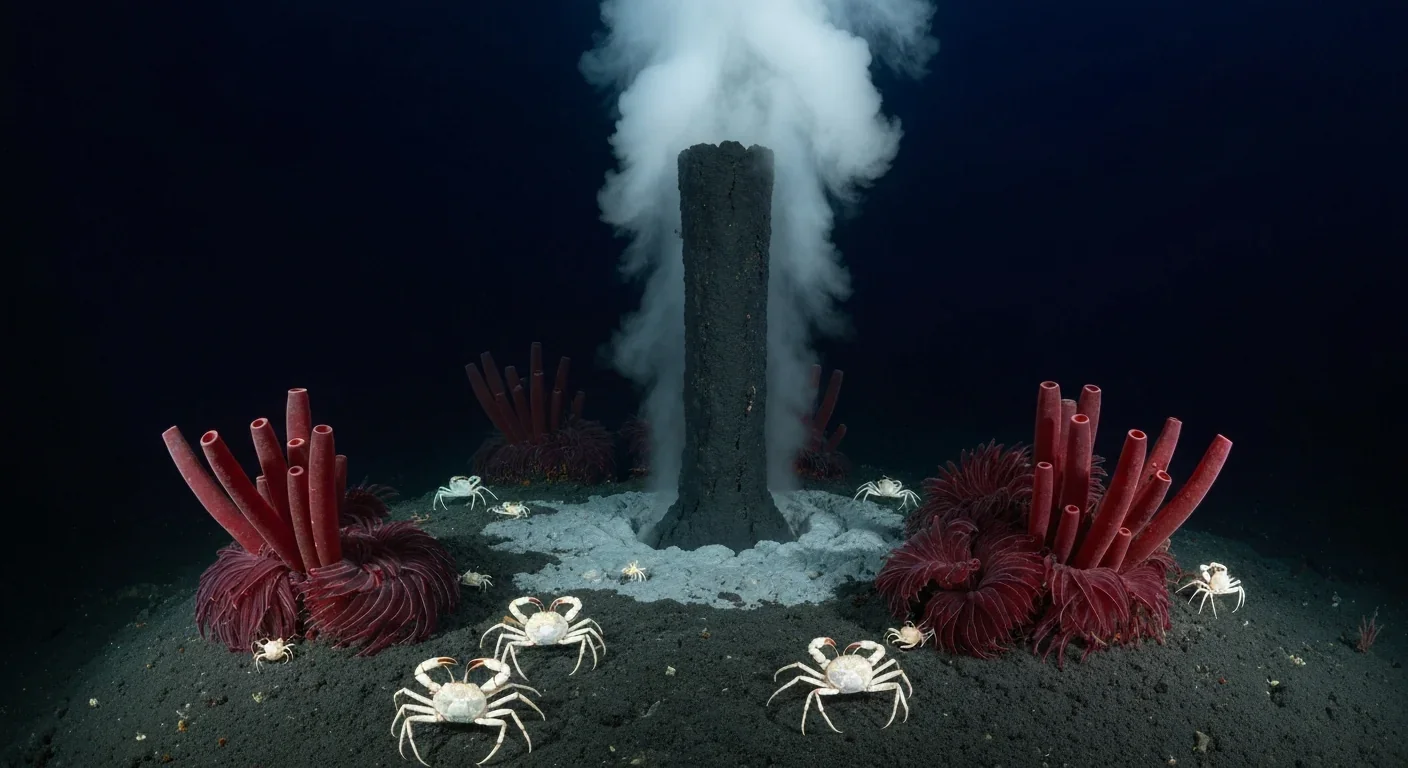

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

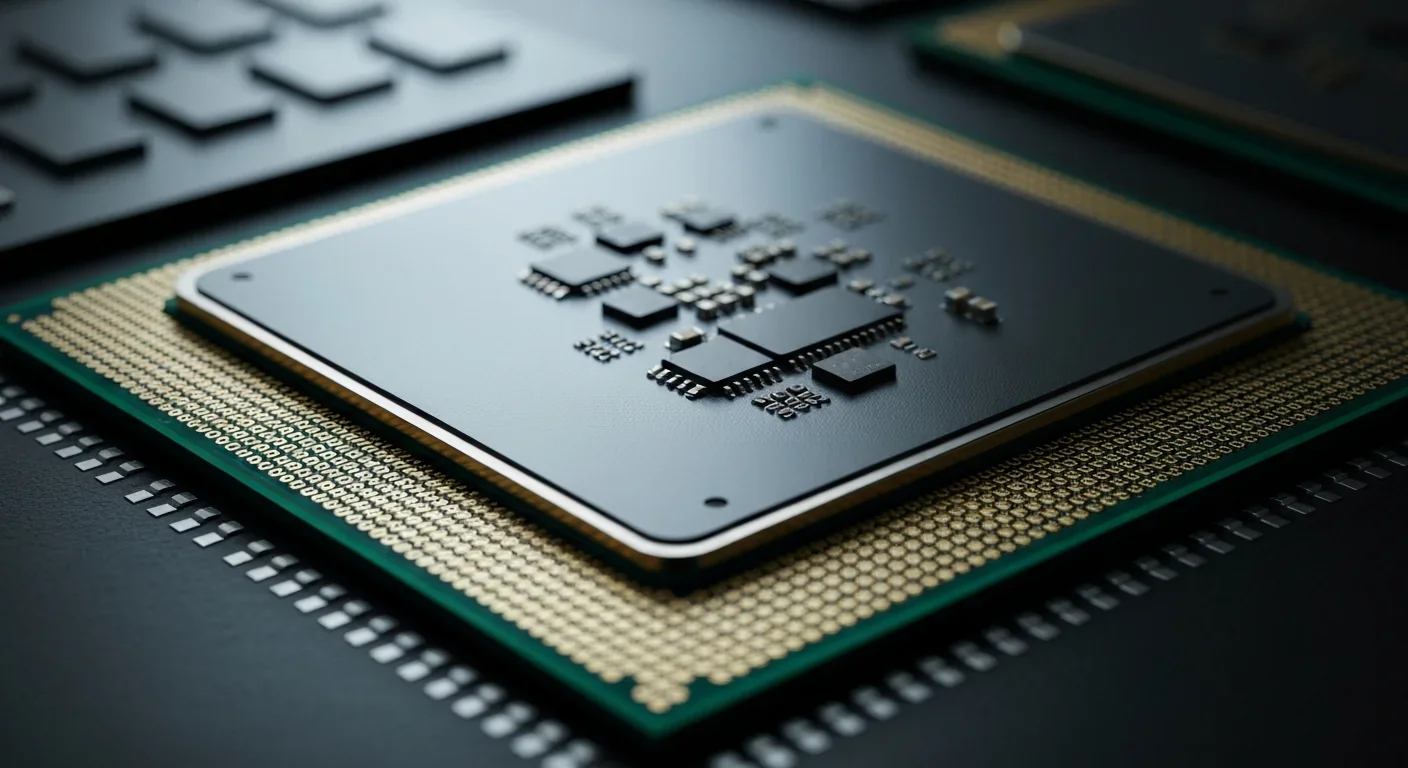

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.