Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: Scientists are revolutionizing the concept of habitable zones beyond simple temperature ranges, discovering that stellar activity, tidal heating, atmospheric composition, and magnetic fields create habitable conditions in unexpected places - from ocean moons warmed by gravitational friction to planets orbiting violent red dwarfs.

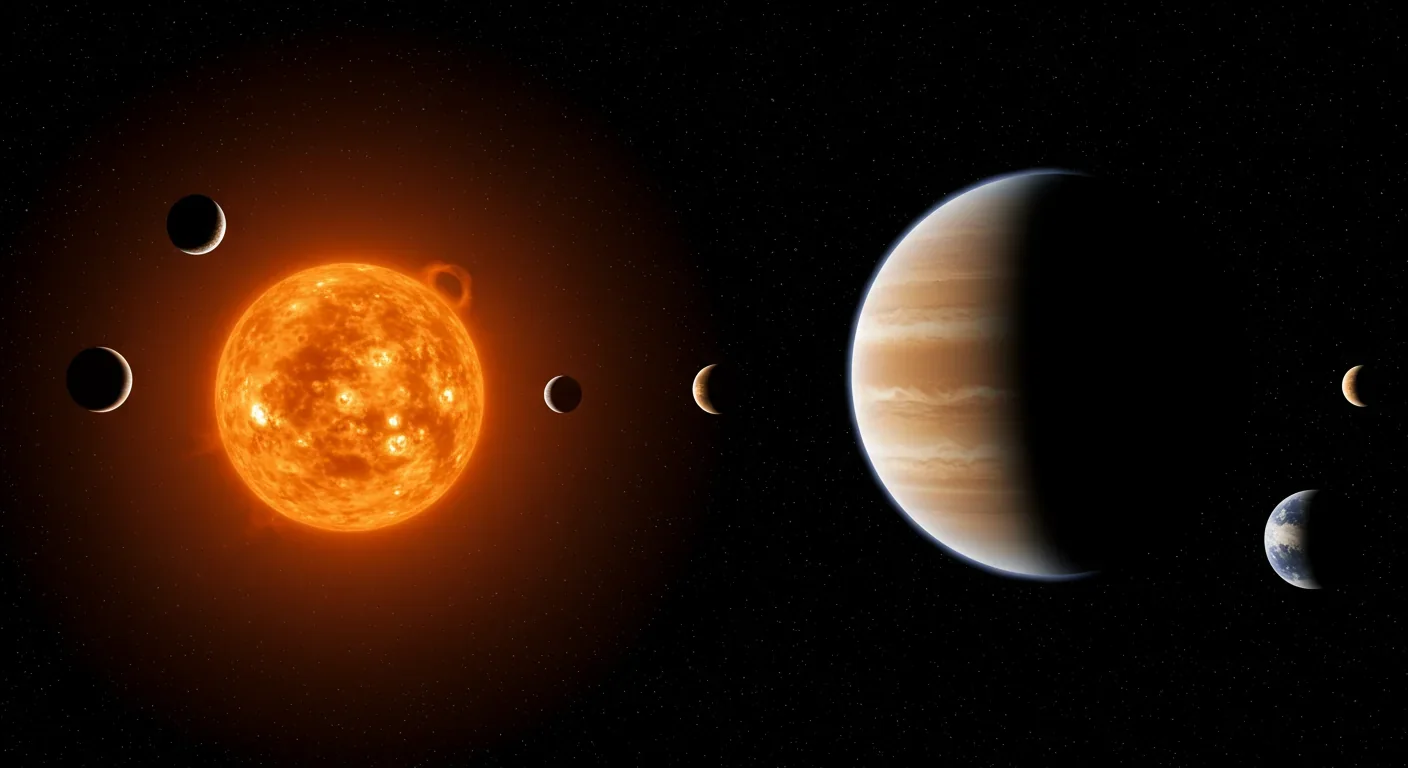

For decades, the search for life beyond Earth has fixated on a seductively simple idea: find planets that are "just right" - not too hot, not too cold - orbiting their stars at the perfect distance where liquid water could pool on their surfaces. This so-called Goldilocks zone has guided billions of dollars in telescope time and shaped the public imagination about alien worlds. But here's what almost nobody tells you: the Goldilocks zone might be the wrong place to look.

Recent discoveries are dismantling this tidy framework faster than astronomers can rewrite their textbooks. Planets once dismissed as frozen wastelands now appear to harbor vast subsurface oceans. Worlds bombarded by stellar radiation - conditions that should sterilize any surface life - may instead possess atmospheres that shield thriving ecosystems. And machine learning algorithms analyzing thousands of exoplanets are revealing patterns that suggest our traditional boundaries were drawn far too conservatively. The habitable zone isn't expanding. It's exploding into something far more nuanced, complex, and promising than anyone anticipated.

The traditional habitable zone concept emerged from a straightforward calculation: measure a star's luminosity, determine the orbital distance where temperatures permit liquid water between 0°C and 100°C, and presto - you've identified where life might exist. For our Sun, that zone stretches roughly from Venus's orbit to Mars's orbit. Simple, elegant, and deeply misleading.

The problem isn't that this calculation is wrong. It's that it's criminally incomplete. Real planetary habitability depends on a cascade of interconnected factors that make temperature look almost trivial by comparison. Does the planet have an atmosphere thick enough to trap heat and redistribute it globally? Does it possess a magnetic field to deflect charged particles that would otherwise strip away that atmosphere molecule by molecule? Is the stellar environment stable enough for complex chemistry to unfold over billions of years?

Temperature is just one variable in a complex equation. Planetary habitability requires the right combination of atmosphere, magnetic field, stellar stability, and dozens of other factors working in concert.

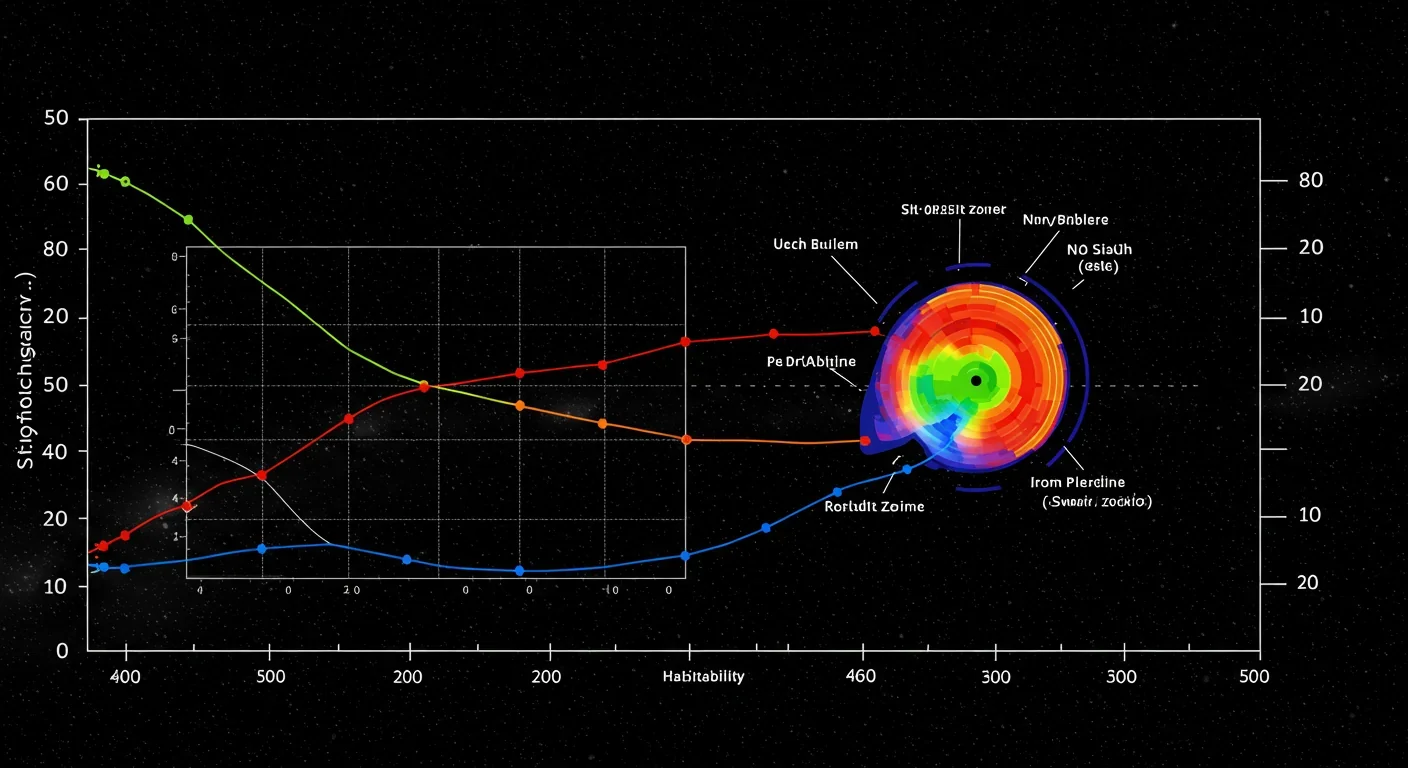

Recent analysis of 5,595 confirmed exoplanets using machine learning reveals just how reductive our old framework was. When researchers trained algorithms to predict habitability based on multiple factors - stellar type, planetary mass, atmospheric composition, orbital characteristics - they achieved 97% accuracy with XGBoost classifiers. More importantly, they discovered that 77.75% of detected planets fall into the "too hot" category, 8.04% are "too cold," and only 4.48% land in traditional habitable zones. But the real surprise? Nearly 10% remained indeterminate because they possessed characteristics that didn't fit conventional categories at all.

This isn't just statistical noise. It's a signal that our conceptual map doesn't match the territory. When JWST trained its instruments on TRAPPIST-1 e - a planet firmly within its star's traditional habitable zone - the telescope found no thick atmosphere. Meanwhile, K2-18 b orbits well outside conventional boundaries yet shows tantalizing hints of biological activity through potential dimethyl sulfide detection. The scorecard reads: traditional habitable zone 0, alternative habitability 1.

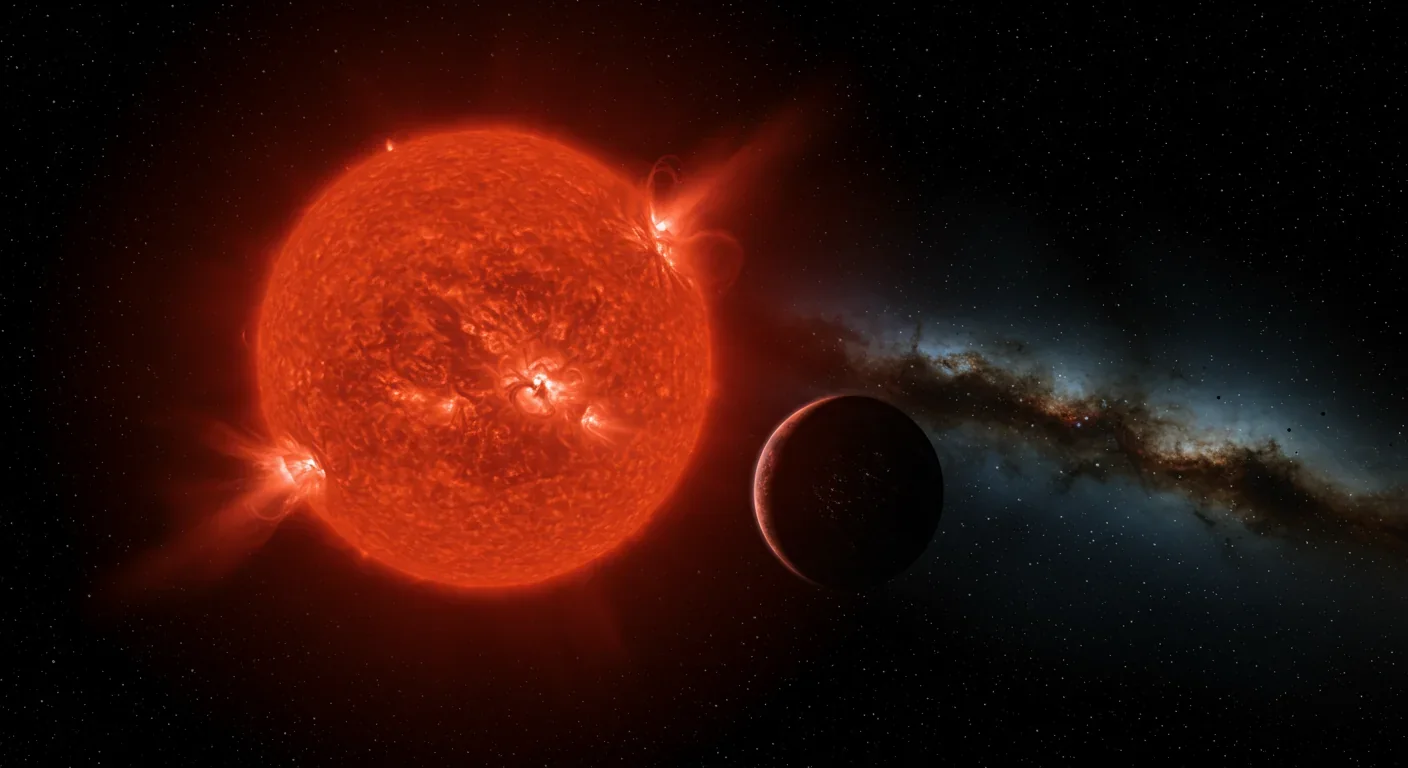

If you're an aspiring organism hoping to evolve on a planet orbiting an M-dwarf star - the most common stellar type in the galaxy - you face a brutal reality check. These small, cool red stars seem perfect for habitability because they're abundant and long-lived, giving evolution plenty of time to work its magic. The catch? They're temperamental as hell.

M-dwarfs regularly unleash stellar flares - massive eruptions of radiation and charged particles - orders of magnitude more powerful than anything our placid Sun produces. A single flare from an active M-dwarf can bathe its planets in radiation equivalent to thousands of years of normal stellar output, compressed into hours. For decades, this seemed like a death sentence for any surface life.

But recent modeling is forcing a recalibration. Studies examining AU Mic system show that while flares absolutely strip away light elements like hydrogen, they have surprisingly limited impact on heavier atmospheric molecules like nitrogen and carbon dioxide. A planet with a substantial magnetic field and a thick CO₂ atmosphere - think Venus but cooler - could weather these stellar tantrums while maintaining surface conditions compatible with certain extremophile life forms.

"Flares strip away light elements but have limited impact on heavier atmospheric molecules. A thick CO₂ atmosphere with magnetic protection could maintain habitable conditions even around active M-dwarfs."

- AU Mic System Research Team

The implications ripple through Proxima Centauri b, our nearest exoplanetary neighbor just 4.2 light-years away. This world orbits a violently active M-dwarf that pelts it with flares. Early models suggested no Earth-like atmosphere could survive. But refined calculations accounting for magnetic protection and atmospheric composition paint a more hopeful picture: life doesn't need an Earth-like atmosphere to thrive. It needs the right atmosphere for its stellar environment. Proxima b's atmospheric survival depends less on Earth-similarity and more on whether it developed robust magnetic shielding early in its history.

The controversy extends to atmospheric pressure's role in UV tolerance. Research on TOI-700 d demonstrates that higher atmospheric pressures dramatically reduce harmful UV radiation reaching a planet's surface - even under bombardment from stellar flares. A thick atmosphere acts like Earth's ozone layer on steroids, filtering out the worst radiation while still permitting enough visible light for photosynthesis. This means planets orbiting active stars might achieve habitability through brute-force atmospheric density rather than orbital positioning.

Here's where things get weird and wonderful. You don't need sunlight at all to power a habitable world. You just need gravitational friction.

Tidal heating occurs when a planet or moon experiences constantly shifting gravitational forces - typically from orbiting a giant planet while other moons tug from different directions. These competing gravitational pulls flex the world like a stress ball being squeezed and released continuously. That flexing generates heat through friction, potentially warming a planet's interior enough to maintain liquid oceans beneath ice shells, completely independent of stellar radiation.

Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus demonstrate this principle spectacularly. Both orbit well outside the traditional solar habitable zone where temperatures plummet to -150°C or colder. Yet beneath their icy crusts, tidal heating maintains vast liquid water oceans - potentially hundreds of kilometers deep - in contact with rocky cores that could provide chemical nutrients. When NASA spacecraft sampled Enceladus's water plumes, they detected organic molecules, salt, and chemical signatures suggesting active hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. Every ingredient for life as we know it, thriving in perpetual darkness.

Tidal heating creates habitable environments billions of kilometers from any star. Europa and Enceladus maintain vast subsurface oceans through gravitational friction alone, completely redefining what "habitable zone" means.

This fundamentally redefines the habitable zone concept. Traditional calculations only consider stellar radiation, but tidal heating adds an entirely independent energy source that could maintain habitable conditions billions of kilometers from any star. Theoretical models examining planets around white dwarfs - the dense remnants of dead stars - show that close-orbiting worlds could maintain surface habitability for billions of years through tidal heating alone, long after their star has cooled to a glowing ember.

The math changes everything. A planet might orbit its star at a distance that seems frozen solid based on temperature calculations, but if it's locked in a gravitational dance with sibling worlds or a giant planet, internal tidal heating could maintain temperate subsurface oceans indefinitely. Research models suggest that stagnant-lid planets - worlds without plate tectonics - might rely heavily on tidal heating and radiogenic decay to sustain long-term habitability, potentially extending habitable lifespans far beyond what stellar radiation alone permits.

Temperature means nothing without context. A planet receiving identical stellar radiation could be a frozen iceball, a steamy greenhouse, or a temperate paradise depending entirely on atmospheric composition and pressure. This insight is reshaping how scientists evaluate exoplanet habitability from light-years away.

Laboratory experiments testing E. coli survival under different atmospheric conditions reveal fascinating patterns. These hardy bacteria survived well beyond traditional habitable zone temperature limits when atmospheric composition shifted. Under high-CO₂ atmospheres, they tolerated temperatures that would normally prove lethal. Conversely, oxygen-rich atmospheres extended habitable temperature ranges in different directions. The takeaway: life adapts to atmospheric chemistry, and atmospheric chemistry determines where temperature boundaries fall.

This explains why exoplanets beyond conservative habitable zones remain compelling targets. A world might orbit too far from its star to maintain liquid water under an Earth-like atmosphere, but could achieve habitability with a thick hydrogen or methane atmosphere that traps heat more efficiently. Current telescopes struggle to characterize exoplanet atmospheres precisely, but next-generation instruments like the Habitable Worlds Observatory will measure atmospheric composition, pressure, and even potential biosignatures with unprecedented accuracy.

Atmospheric dynamics introduce another layer of complexity. Climate modeling across different planetary rotation rates and orbital configurations shows that slow rotators distribute heat more evenly across their surfaces, potentially maintaining habitable conditions further from their stars than fast-spinning worlds. A planet tidally locked to its star - forever showing the same face to its sun - might develop atmospheric circulation patterns that transport heat from its dayside to its nightside, preventing runaway glaciation on one hemisphere and runaway greenhouse effects on the other.

"Atmospheric composition matters more than temperature. The same planet could be frozen, temperate, or scorching depending entirely on what gases surround it and at what pressure."

- Atmospheric Habitability Research

The implications extend to atmospheric evolution. Planets aren't static; their atmospheres change over billions of years through volcanic outgassing, impact delivery, atmospheric escape, and biological processes. A biosphere itself can extend habitable timespans on stagnant-lid planets by regulating atmospheric chemistry and preventing runaway climate feedback loops. Life doesn't just inhabit habitable zones - it actively maintains them.

When humans define habitable zones, we carry biases from our sample size of one: Earth. We assume certain conditions because they work here, but "works for Earth" doesn't equal "necessary for all life." Machine learning algorithms, trained on thousands of planetary systems, spot patterns that transcend human assumptions.

Recent ML analysis revealed that traditional habitable zone definitions suffered from severe detection bias. Current telescopes most easily spot close-in, large planets orbiting small stars - exactly the populations most likely to fall outside conventional habitable zones. When algorithms corrected for this observational bias and weighted planetary characteristics differently, the number of potentially habitable worlds increased dramatically.

The algorithms also identified surprising correlations. Planets at the outer edges of habitable zones around K-type orange dwarfs showed habitability signatures comparable to Earth-zone planets around G-type yellow dwarfs like our Sun. This suggests K-dwarfs might represent "Goldilocks stars" - cooler than the Sun, longer-lived, less active than M-dwarfs, potentially offering optimal conditions for stable, long-term habitability.

Machine learning excels at integrating multiple variables simultaneously - something human intuition struggles with. An algorithm can simultaneously evaluate stellar luminosity, variability, and age; planetary mass, radius, and composition; orbital eccentricity and inclination; atmospheric retention probability; magnetic field strength estimates; and tidal heating potential. It weighs these factors against observed characteristics of the only confirmed habitable world we know, then extrapolates to predict habitability likelihood across thousands of exoplanets.

The results are already guiding observational priorities. When telescope time is precious and demand exceeds supply by orders of magnitude, astronomers need ranked target lists. ML-generated habitability scores provide that ranking, ensuring limited resources focus on worlds most likely to yield positive results. JWST's target selection for atmospheric characterization increasingly relies on these algorithmic assessments.

The traditional habitable zone obsesses over liquid water because Earth life requires it. But that assumption may reflect terrestrial parochialism more than universal necessity. Astrobiologists increasingly consider alternative solvents that could support biochemistry under radically different conditions.

Liquid methane, for example, remains liquid between -182°C and -161°C at Earth atmospheric pressure. Saturn's moon Titan has surface lakes and rivers of liquid methane at temperatures around -179°C - cold enough to make traditional habitable zones look scorching by comparison. Could methane-based life exist there? The chemistry would differ fundamentally from water-based biochemistry, with different reaction kinetics and molecular structures, but theoretical models show it's thermodynamically plausible.

Ammonia-water mixtures remain liquid at temperatures far below pure water's freezing point, potentially extending habitable zones outward significantly. Sulfuric acid could serve as a solvent in extremely hot, Venus-like conditions. Some researchers even speculate about supercritical CO₂ supporting exotic biochemistries under high pressure and temperature.

These aren't idle speculations. They represent testable hypotheses that drive instrument design for future missions. If we search for biosignatures assuming Earth-like metabolisms, we'll miss alternative life forms that produce entirely different chemical signatures. Biosignature detection strategies now incorporate predictions for non-water-based metabolisms, ensuring our searches remain agnostic about biochemical specifics while focusing on thermodynamic and information-theoretic principles that should apply universally.

The challenge lies in distinguishing biological from geological processes across interstellar distances. On Earth, oxygen's presence in our atmosphere represents a biosignature because geological processes alone can't maintain such reactive gas concentrations. But would we recognize alternative biosignatures from methane-based or ammonia-based metabolisms? Studies of Earth's extremophiles - organisms thriving in acid lakes, Antarctic ice, deep-ocean hydrothermal vents, and miles underground - help calibrate our expectations for what life signatures might look like under alien conditions.

Zoom out from individual planetary systems and another layer emerges: galactic habitability. Not all neighborhoods in the Milky Way offer equally promising conditions for life. The galaxy's inner regions experience frequent supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, and intense stellar density that could periodically sterilize planetary surfaces. The outer regions lack sufficient metallicity - heavy elements like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and iron - necessary for building rocky planets and complex chemistry.

Earth sits in the galactic habitable zone, roughly 25,000 light-years from the Milky Way's center - far enough to avoid radiation catastrophes, close enough that earlier stellar generations enriched our region with heavy elements through supernovae. This cosmic real estate consideration affects Drake Equation calculations estimating intelligent civilizations in our galaxy.

But even galactic habitability isn't monolithic. Globular clusters - dense stellar groupings - were long dismissed as sterile environments because their metal-poor stars seemed incapable of forming Earth-like planets. Recent discoveries challenge this, finding planets around unexpectedly metal-poor stars that nonetheless maintain rocky compositions. Perhaps life doesn't require solar metallicity levels after all - it just needs enough heavy elements to work with, and stellar metallicity thresholds remain poorly understood.

The galactic perspective also considers time. Early in cosmic history, the universe lacked sufficient heavy elements for any rocky planets. The first galaxies were sterile by necessity. Only after multiple generations of stars lived, died, and seeded the cosmos with their fusion products did planetary habitability become possible. We live in a cosmic era where conditions have finally ripened for life - but it's an era that could span trillions of years as small stars slowly burn through their fuel supplies.

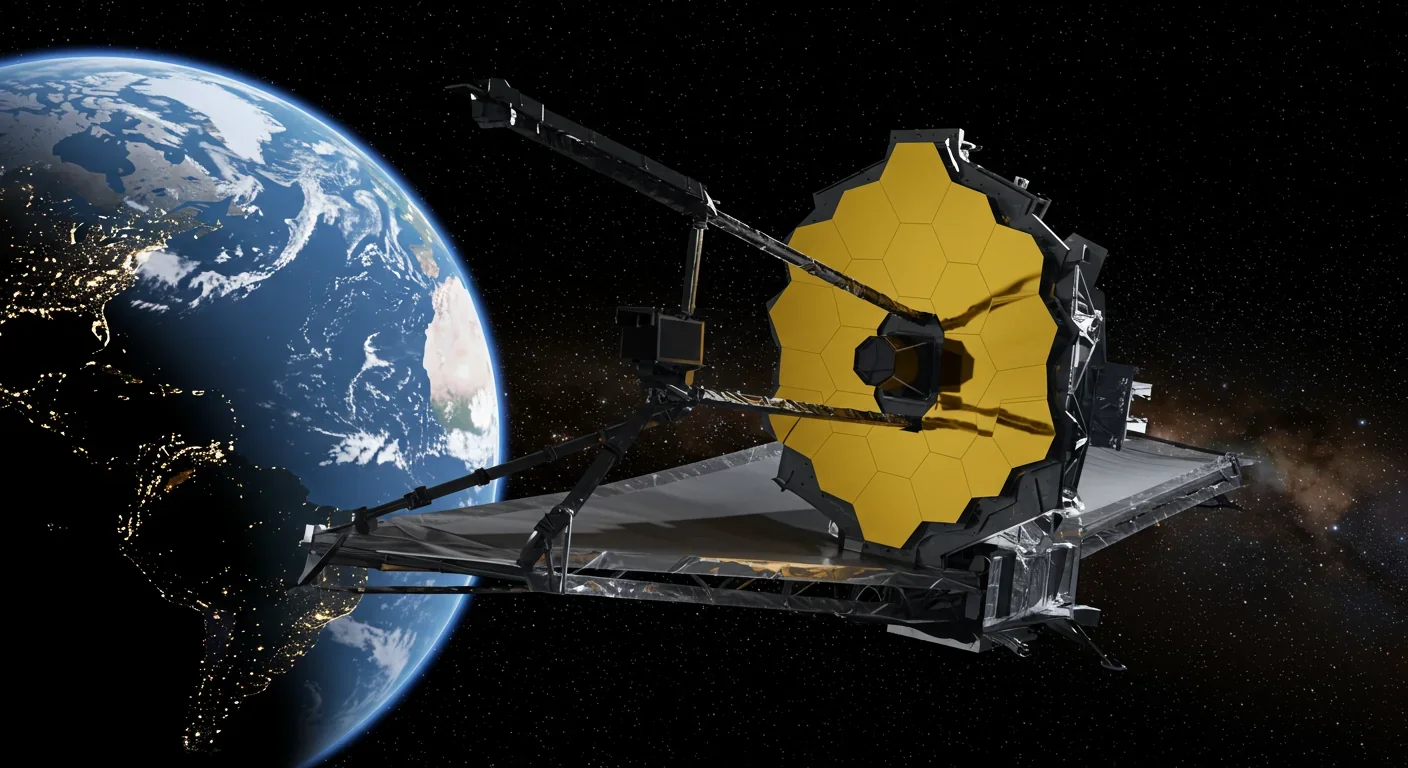

The James Webb Space Telescope represents a watershed moment in habitability science. Previous telescopes detected exoplanets as shadows passing in front of stars or gravitational tugs on stellar motion. JWST does something unprecedented: it analyzes exoplanet atmospheres by measuring starlight filtering through those atmospheres during transits, revealing chemical fingerprints with extraordinary precision.

Early results are already rewriting assumptions. K2-18 b, a mini-Neptune orbiting an M-dwarf 120 light-years away, shows potential signs of dimethyl sulfide in its atmosphere - a molecule that on Earth is produced almost exclusively by biological processes. The detection remains tentative, requiring confirmation through additional observations, but if verified, it would represent the first biosignature detected on an exoplanet. And crucially, K2-18 b orbits outside conservative habitable zone boundaries, demonstrating exactly why expanded habitability concepts matter.

K2-18 b shows potential biosignatures despite orbiting outside traditional habitable zones - proof that our expanded understanding is essential for finding life beyond Earth.

TRAPPIST-1 system observations tell a more sobering story. This remarkable system contains seven Earth-sized planets orbiting an ultra-cool M-dwarf, with three planets firmly in the traditional habitable zone. JWST examined TRAPPIST-1 e, finding no evidence of a thick atmosphere. The planet's lack of atmospheric insulation doesn't necessarily rule out habitability - subsurface life or a thin atmosphere might still exist - but it tempers earlier optimism.

What JWST reveals through these observations transcends individual planetary results. It's teaching us which atmospheric signals are easy or difficult to detect at current sensitivities, guiding the design of next-generation telescopes. It's showing which planetary characteristics permit atmospheric retention around active M-dwarfs and which don't. Most importantly, it's providing real data about atmospheric diversity that calibrates theoretical models and machine learning algorithms, making predictions about unstudied systems increasingly accurate.

As habitability science evolves, so does observational strategy. The coming decade will see multiple missions specifically designed to characterize potentially habitable exoplanets with unprecedented detail.

The Habitable Worlds Observatory, currently in planning stages, aims to directly image exoplanets around Sun-like stars - separating planetary light from overwhelming stellar glare. This capability matters because transits only work for planetary systems oriented edge-on from Earth's perspective, missing most systems entirely. Direct imaging opens access to planets at all orbital inclinations, dramatically expanding the target pool.

But which targets deserve priority when observation time remains scarce? Recent research proposes a "continuous habitable zone" metric that scores planetary targets based on how long they've resided in their star's habitable zone over the stellar lifetime. A planet that just recently drifted into the habitable zone as its star brightens with age scores lower than one that's maintained stable habitable conditions for billions of years. The logic is sound: life needs time to arise, evolve, and produce detectable biosignatures. Prioritizing planets with long habitability timespans maximizes chances of positive detection.

This approach particularly favors K-type orange dwarf stars. These stars live longer than G-type yellow dwarfs like the Sun, providing extended windows for biological evolution, but remain more stable than M-dwarfs, avoiding the flare activity that threatens atmospheric retention. Their habitable zones sit at convenient orbital distances for current telescope capabilities - close enough for strong signals, far enough that planets aren't tidally locked.

The search also extends to white dwarf systems. These stellar remnants lack fusion, but their residual heat could maintain habitable conditions for close-orbiting planets through a combination of stellar radiation and tidal heating. White dwarfs represent the final fate of most stars, including our Sun, and they'll outnumber all other stellar types once the universe ages. If life can survive stellar evolution and adapt to white dwarf environments, habitable worlds might remain common even in the cosmic far future.

Perhaps the most radical expansion of habitable zone concepts involves planets with no star at all. Rogue planets - worlds ejected from their parent systems through gravitational interactions - drift through interstellar space in perpetual darkness. Estimates suggest they might outnumber stars in the galaxy by significant margins.

Could life exist on such worlds? Not through stellar radiation, obviously. But thick atmospheres providing greenhouse insulation, radioactive decay heating planetary interiors, and tidal heating if the rogue planet retains moons could potentially maintain subsurface liquid water for billions of years. The surface would freeze instantly in the 3-Kelvin background radiation of interstellar space, but deep oceans insulated by ice shells kilometers thick might remain liquid and temperate.

Evidence for this possibility exists in our solar system. Europa, Enceladus, and potentially Titan might harbor habitable subsurface oceans maintained by tidal and radiogenic heating with minimal solar contribution. If Jupiter or Saturn were ejected into interstellar space tomorrow, their moons would barely notice - the energy sources maintaining their habitability originate internally, not from the Sun.

Rogue planets present detection challenges since they emit no light and don't transit stars. Current searches rely on gravitational microlensing - the temporary brightening of distant stars as a rogue planet's gravity focuses their light - but this technique only glimpses rogues briefly during chance alignments. Most drift undetected through the galactic dark. If they harbor life, it exists in conditions so alien that even calling them "planets" feels inadequate.

The evolution of habitable zone science carries profound implications for how we search for life and what we expect to find. The old model was simple: look for Earth-sized planets orbiting Sun-like stars at Earth's orbital distance. This new paradigm is messier, more complex, and far more hopeful.

By recognizing habitability's multidimensional nature, we've dramatically expanded the number of potentially habitable worlds. Every M-dwarf system becomes a candidate if we properly account for atmospheric composition and magnetic protection. Every system with giant planets gains candidates through potentially habitable moons. Every star enters a phase during its evolution where its habitable zone migrates, potentially bringing previously frozen worlds into habitable conditions.

But complexity cuts both ways. More candidates means more targets competing for limited telescope time. More variables means greater uncertainty in habitability predictions. And expanded habitability concepts raise uncomfortable questions: if life can arise in such diverse environments, why haven't we detected obvious biosignatures yet? Does this suggest life is rarer than we hoped, or just that we're looking for the wrong signals?

The answer may lie in distinguishing between "habitable" and "inhabited." Creating conditions where life could potentially arise differs dramatically from life actually arising, surviving, and evolving to produce detectable biosignatures. Earth spent billions of years as a habitable world before oxygen-producing photosynthesis emerged and transformed our atmosphere into an obvious biosignature visible across interstellar distances. How many potentially habitable worlds host only microbial ecosystems that leave subtle signatures easily missed by current instruments?

We're entering an era where habitable zone science transitions from theoretical speculation to empirical discipline. Each new exoplanet atmospheric spectrum, each refined climate model, each laboratory experiment testing extremophile survival under exotic conditions adds another data point. The picture emerging from these accumulating observations is clear: habitability is far stranger, more diverse, and more wonderful than traditional frameworks suggested.

The coming decades will see machine learning algorithms trained on exponentially larger datasets as missions like PLATO and ARIEL characterize thousands of exoplanet atmospheres. These algorithms will identify correlations and patterns invisible to human researchers, potentially revealing habitability indicators we haven't considered. They'll optimize target selection for future direct-imaging missions, ensuring resources focus on worlds most likely to harbor detectable life.

We'll map atmospheric compositions across diverse planetary types, learning which atmospheres survive around which stellar types under what conditions. We'll catalog planetary magnetic field strengths and understand how they correlate with atmospheric retention. We'll watch stellar activity over multiple cycles, quantifying how flares affect habitability in real systems rather than theoretical models.

And perhaps most intriguingly, we'll begin testing these refined habitability concepts against biosignature detections - or conspicuous absences. If expanded habitability models predict vast numbers of habitable worlds yet biosignatures remain elusive, that itself becomes crucial data. It suggests bottlenecks in life's origin or evolution that we don't currently understand, hinting at the answer to one of humanity's deepest questions: are we alone?

The habitable zone isn't a simple ring around a star anymore. It's a complex, multidimensional volume in parameter space defined by stellar characteristics, planetary properties, atmospheric composition, orbital dynamics, tidal interactions, magnetic fields, and probably factors we haven't identified yet. Within that volume lie worlds stranger than science fiction predicted - ocean moons warmed by gravitational squeezing, planets with hydrogen atmospheres thick enough to trap meager starlight from dying stars, and perhaps most tantalizing, worlds where life follows biochemical paths we can barely imagine.

The Goldilocks zone was a starting point, a first approximation that served us well when we knew of only nine planets. But we've discovered thousands more, and they're teaching us that the universe's habitable real estate is far more extensive than we dared hope. Somewhere out there, on worlds orbiting orange dwarfs in the galaxy's outskirts, or huddled beneath ice shells around rogue planets, or bathed in the glow of ancient white dwarfs, life might have found a way. Our task now is learning to recognize it.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.