Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: Brown dwarfs, celestial objects too massive to be planets but too small to become stars, harbor extreme weather systems including winds exceeding 2,000 km/h, storm systems larger than Earth, and clouds made of molten iron and vaporized rock. Using the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers are mapping these distant weather patterns, revealing insights crucial for understanding exoplanet atmospheres.

Imagine a world where hurricanes span an entire hemisphere, where winds scream across cloud decks at 2,000 kilometers per hour, and where the atmosphere rains molten iron droplets instead of water. This isn't science fiction. It's weather on brown dwarfs, the universe's most extreme meteorological laboratories, and astronomers are finally cracking the code on how to study storms that rage light-years away.

Brown dwarfs occupy the twilight zone between planets and stars. Too massive to be planets but too lightweight to ignite the nuclear fusion that powers true stars, these "failed stars" have fascinated astronomers since their discovery in the 1990s. What researchers didn't expect was that these celestial misfits would harbor weather systems more violent and complex than anything in our solar system.

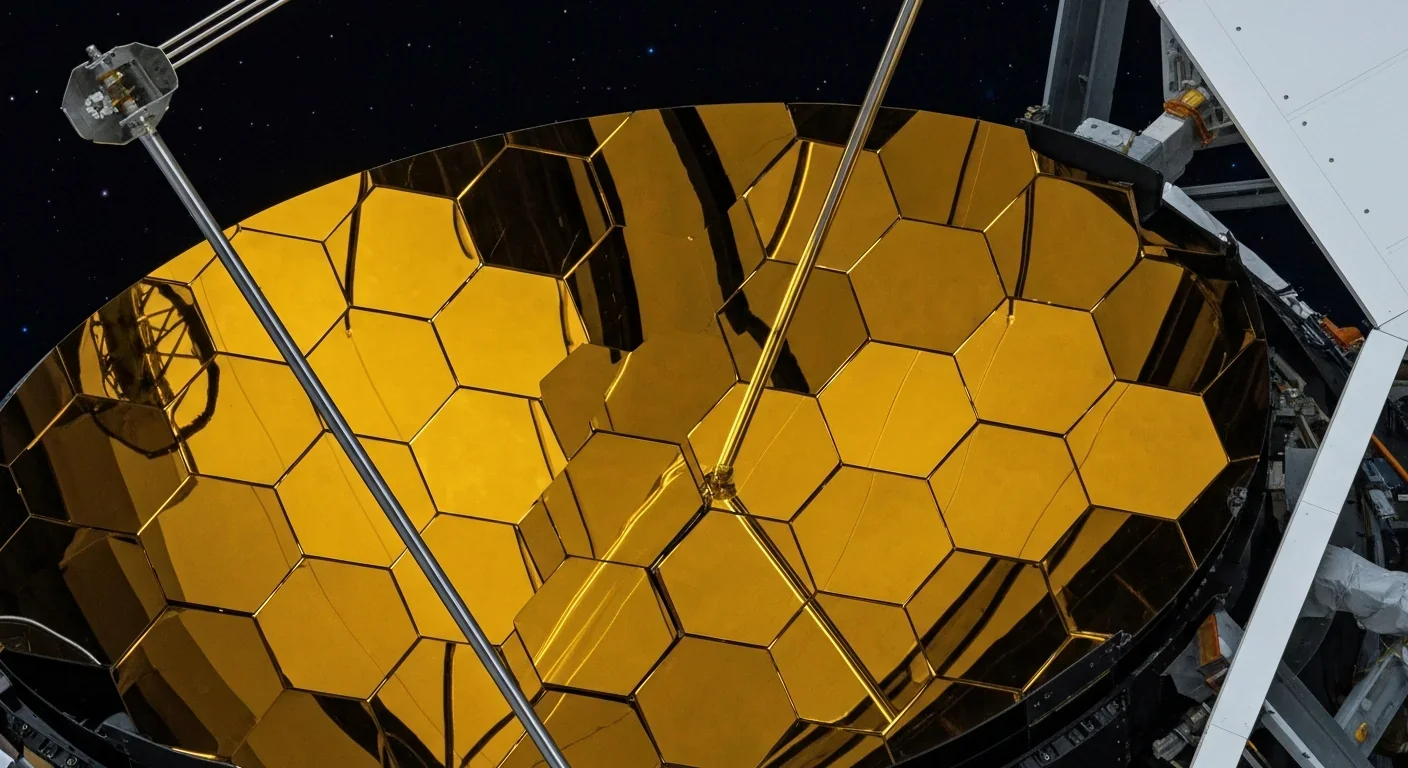

Thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope and decades of infrared observations, we're now watching weather unfold on objects dozens of light-years away. The picture emerging is spectacular: rotating storm bands that dwarf Jupiter's Great Red Spot, temperature swings of hundreds of degrees, and atmospheric chemistry so exotic it's rewriting textbooks on planetary science.

Brown dwarfs exist in the awkward middle ground of cosmic objects. With masses ranging from about 13 to 80 times that of Jupiter, they're far too heavy to be planets but fall short of the roughly 8% of the Sun's mass needed to sustain hydrogen fusion. Without fusion, they can't become proper stars. Instead, they're cosmic leftovers that glow dimly from leftover heat and, in some cases, limited deuterium burning.

Size-wise, brown dwarfs are surprisingly compact. Most are roughly Jupiter-sized, despite being dozens of times more massive. This density creates crushing atmospheric pressures and extreme conditions. The heaviest brown dwarfs push up against the stellar boundary, while the lightest blur into the category of rogue planets, massive worlds drifting through space without a parent star.

Brown dwarfs pack dozens of Jupiter masses into a Jupiter-sized sphere, creating atmospheric pressures and conditions impossible to replicate in any Earth laboratory.

Temperature defines much of a brown dwarf's character. The hottest examples, fresh from formation, can reach 3,500 Kelvin or higher, hot enough to vaporize iron. The coldest known brown dwarf, WISE 0855, registers a frigid 285 Kelvin, barely warmer than Earth's polar regions. This temperature gradient creates different atmospheric regimes, each with distinct weather patterns and cloud compositions.

Unlike stars, brown dwarfs cool continuously over billions of years. They transition through spectral classes, M to L to T to Y, each representing a temperature drop and corresponding shift in atmospheric chemistry. It's like watching a star's entire life cycle compressed and slowed, visible through changing weather patterns.

The weather on brown dwarfs makes Earth's most violent storms look tame by comparison. Wind speeds routinely exceed 2,000 kilometers per hour, nearly double the fastest winds ever recorded on Jupiter. These aren't localized gusts but planet-spanning jet streams that circle entire hemispheres.

Rotation drives much of this atmospheric violence. Some brown dwarfs spin incredibly fast, with rotation periods as short as 1.4 hours compared to Jupiter's leisurely 10-hour day. This rapid rotation, combined with internal heat, creates powerful Coriolis forces that organize winds into massive zonal bands. Think of Jupiter's familiar stripes, but supercharged and unstable.

Temperature variations reveal the scale of brown dwarf weather systems. The hottest brown dwarfs show day-night temperature differences exceeding 1,000 Kelvin. On one particularly extreme example, astronomers measured an 8,000 Kelvin dayside against a 2,000 Kelvin nightside, a temperature swing that would vaporize and recondense metals as the planet rotates.

"What's remarkable is that deeper in the atmosphere, these temperature swings nearly disappear, with variations of less than 5 degrees Celsius even as the visible surface churns violently."

- JWST Atmospheric Observations

This suggests massive vertical heat transport, storm systems so large they reach from the cloud tops down through kilometers of dense atmosphere. The sheer power required to move heat on this scale staggers the imagination.

Storm structures themselves differ dramatically across brown dwarf types. Some, like Luhman 16B, show organized banded structures similar to Jupiter. Others, like the super-Jupiter VHS 1256b, display chaotic dust storms with no stable pattern at all. The transition from ordered to chaotic appears linked to mass and rotation rate, though researchers are still mapping the boundaries.

The sheer scale of individual storm features staggers the imagination. Brightness variations in brown dwarf atmospheres can exceed 30%, suggesting storm systems larger than Earth rotating in and out of view. These aren't discrete hurricanes like on Earth but continent-sized cells in the atmospheric circulation.

If brown dwarf winds are extreme, their clouds are downright alien. Forget water vapor. Brown dwarf atmospheres host clouds made of vaporized rock, molten iron droplets, and minerals that would be solid on Earth's surface.

Temperature determines cloud composition. The hottest brown dwarfs feature iron and metal oxide clouds floating in their upper atmospheres. As brown dwarfs cool, these give way to silicate clouds, composed of minerals like forsterite, the same material found in Earth's mantle. Cooler still, and water ice clouds appear, though at temperatures that would boil water on Earth's surface.

Luhman 16B, one of the best-studied brown dwarfs, provides a perfect example. Observations reveal clouds of silicate rocks and molten iron droplets swirling in its 830-degree-Celsius atmosphere. These clouds aren't evenly distributed but gather in bands and patches, rotating into and out of view as the brown dwarf spins every 4 hours and 52 minutes.

On the hottest brown dwarfs, it literally rains molten iron. As cloud decks rotate between hot and cool regions, iron vaporizes on the dayside and condenses into droplets on the nightside, falling through the atmosphere like metallic rain.

Chemical complexity adds another layer. Brown dwarf atmospheres contain water vapor, methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and ammonia, but in proportions that shift with temperature and pressure. WISE 0855, the coldest known brown dwarf, yielded the first detection of silane in a celestial atmosphere, a molecule never before seen beyond Earth laboratories.

Cloud dynamics drive much of the brightness variation astronomers observe. As patchy cloud decks rotate, they alternately reveal and conceal hotter layers beneath, creating photometric variability of 10-30%. Some brown dwarfs show multiple periodicities, suggesting different cloud layers rotating at different speeds, much like Earth's jet streams.

Vertical structure matters enormously. Observations indicate multiple stacked cloud layers at different pressures and temperatures. SIMP J0136, a rapidly rotating brown dwarf, shows evidence of iron clouds in one layer and forsterite clouds in another, with potential hemispheric asymmetry. The interaction between these layers creates complex three-dimensional weather that's only beginning to be understood.

Studying weather on objects you can never visit, so distant they appear as single points of light, requires detective work that borders on magic. Astronomers can't send probes or take close-up photos. Instead, they watch how brown dwarfs' light changes over time and decode those variations into weather maps.

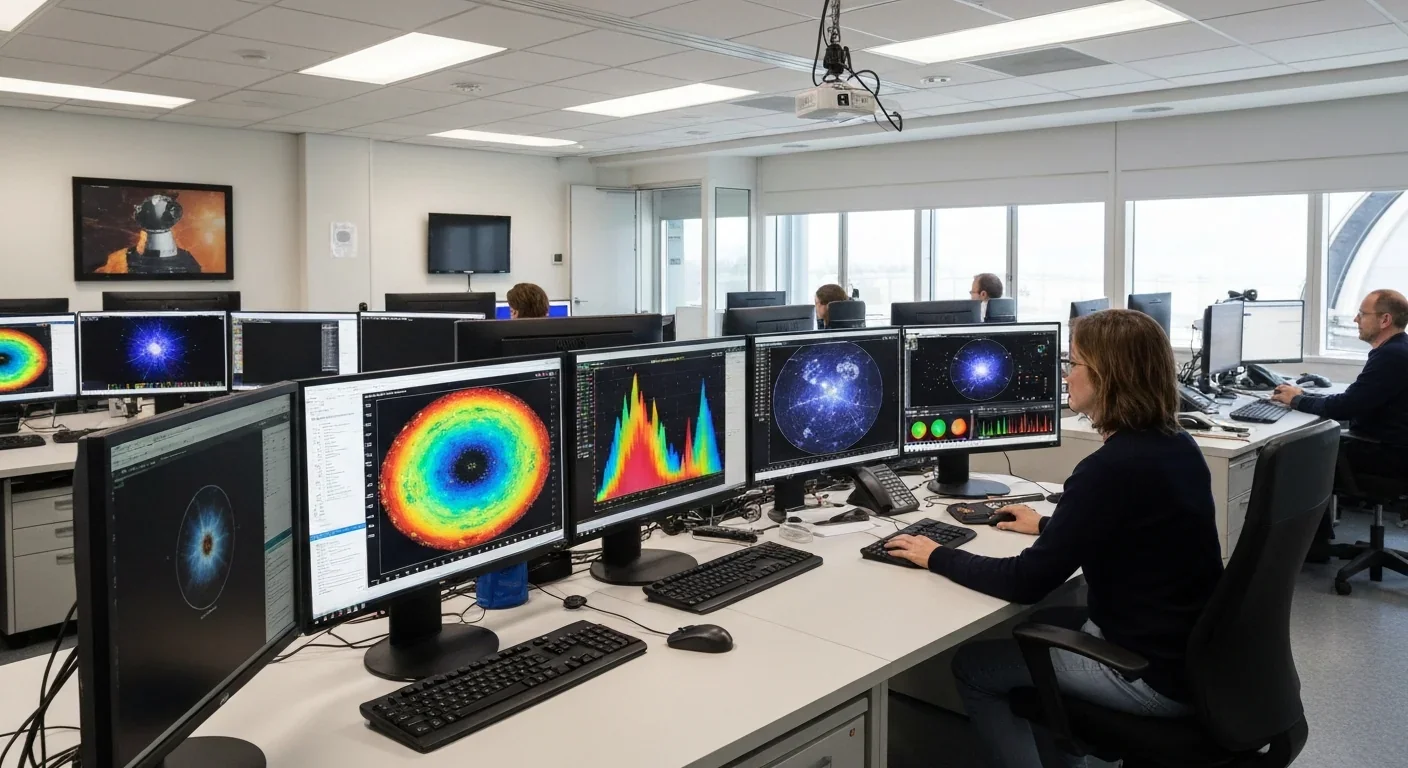

The technique, called time-resolved spectroscopy, works like this: As a brown dwarf rotates, different atmospheric features rotate into view. A bright, cloud-free region appears brighter; a dark, cloudy patch appears dimmer. By monitoring brightness changes across many wavelengths simultaneously, astronomers can infer what's happening in the atmosphere.

Different molecules absorb different wavelengths of light. Water vapor absorbs strongly in certain infrared bands, methane in others, carbon monoxide in still others. When a cloud deck rich in, say, water vapor rotates into view, those specific wavelengths dim more than others. By tracking these spectroscopic deviations, researchers map chemical composition across the visible hemisphere.

The James Webb Space Telescope revolutionized this work. Its infrared sensitivity and spectroscopic capabilities allow astronomers to monitor brown dwarfs continuously for hours, building up detailed rotational maps. Recent observations of WISE 1049AB, a brown dwarf binary system, involved seven months of monitoring, capturing how weather patterns evolved over time.

"We're essentially doing weather forecasting for objects light-years away by reading the fingerprints in their light. Each wavelength tells us about temperature, chemistry, and cloud cover at different atmospheric levels."

- JWST Brown Dwarf Research Team

Harmonic analysis teases out atmospheric structure. Just as musical notes can be decomposed into fundamental frequencies and harmonics, brightness variations can be broken into components. The fundamental frequency reveals rotation period. Higher harmonics indicate atmospheric complexity: second harmonics might reveal two major storm cells, odd harmonics could indicate north-south asymmetry.

Atmospheric modeling completes the picture. Researchers use the observational constraints, temperature, brightness variations, chemical abundances, to feed sophisticated computer models that simulate brown dwarf atmospheres. These models predict wind speeds, cloud formation, and heat transport, which can then be tested against new observations in an iterative process.

Contribution functions add another analytical tool. These mathematical constructs reveal which atmospheric pressure levels contribute most to the light at each wavelength. This allows astronomers to effectively peer through the atmosphere layer by layer, seeing whether a particular molecule exists near the top or deep below the clouds.

Several brown dwarfs have become celestial weather stations, monitored repeatedly to track how their atmospheres evolve. Each reveals something unique about brown dwarf meteorology.

Luhman 16B, at just 6.5 light-years away, ranks as the closest brown dwarf system to Earth and one of the most observed. With a mass of 28 Jupiters and surface temperature of 830 degrees Celsius, it shows organized cloud bands and 30% brightness variations. Its fast rotation creates powerful jet streams, and observations reveal wavelength-dependent brightness changes that trace different cloud layers.

SIMP J0136 holds the record for extreme rotation: just 2.4 hours per day. This ultra-fast spin creates intense Coriolis forces, possibly explaining the hemispheric cloud asymmetry detected in JWST observations. The atmosphere shows evidence of both iron and forsterite clouds at different pressure levels, with chemical deviations in water, carbon monoxide, and methane bands revealing complex atmospheric chemistry.

VHS 1256b, a super-Jupiter about 40 light-years away, defies the organized weather patterns seen on most brown dwarfs. Instead of stable bands, it exhibits chaotic dust storms driven by large-scale equatorial waves. This chaotic regime offers clues about the boundary conditions where orderly atmospheric circulation breaks down.

WISE 1049AB, a binary brown dwarf system, allowed astronomers to compare weather on two objects in the same environment. Seven months of JWST monitoring revealed that both components rotate with nearly identical 5.28-hour periods but show different atmospheric variability patterns, suggesting that initial conditions or small mass differences create divergent atmospheric evolution.

WISE 0855, the coldest known brown dwarf at 285 Kelvin, pushes into temperature regimes previously only seen on planets. Its atmosphere contains water ice clouds and yielded the first detection of silane in a celestial object. Studying WISE 0855 helps astronomers understand how brown dwarf atmospheres transition into giant planet atmospheres.

Brown dwarfs serve as natural laboratories for atmospheric physics in extreme regimes impossible to replicate on Earth or study in our solar system. The insights gained reach far beyond these failed stars themselves.

Understanding brown dwarf atmospheres directly informs exoplanet research. Many hot Jupiters, giant planets orbiting close to their stars, have temperatures and atmospheric pressures similar to brown dwarfs. The techniques developed to map brown dwarf weather apply directly to studying exoplanet atmospheres, though exoplanets present additional challenges due to their proximity to bright host stars.

Every brown dwarf we study teaches us how to read the atmospheres of distant exoplanets. The techniques we're developing now will help us identify potentially habitable worlds in the coming decades.

The diversity of brown dwarf weather patterns reveals which factors control atmospheric behavior. Rotation rate clearly matters: faster rotation tends to create stronger jets and more organized bands. Temperature determines cloud composition and chemistry. Mass affects internal heat sources and atmospheric pressure. Mapping these relationships creates a framework for predicting atmospheric characteristics across a wide range of celestial objects.

Chemical disequilibrium in brown dwarf atmospheres teaches lessons about atmospheric chemistry under extreme conditions. Some molecules appear in abundances that shouldn't exist if the atmosphere were in chemical equilibrium. This reveals powerful vertical mixing, thermochemical instabilities, and possibly biological processes analogous to Earth's photosynthesis disturbing atmospheric balance, though without life.

The transition between chaotic and ordered atmospheric regimes interests climate scientists. Understanding why some brown dwarfs maintain stable jets while others show chaotic turbulence might apply to Earth's own climate and the transitions between different circulation patterns that drive climate change.

Formation theories benefit from brown dwarf observations. The boundary between planets and brown dwarfs remains contested. Some researchers argue formation mechanism matters more than mass: objects forming like stars via cloud collapse qualify as brown dwarfs, while those forming in protoplanetary disks count as planets. Atmospheric composition and weather patterns might preserve evidence of formation pathways.

The James Webb Space Telescope's capabilities are just beginning to be tapped for brown dwarf science. Future observations will push into longer time baselines, monitoring individual brown dwarfs for years to track long-term climate evolution and search for seasonal changes.

Upcoming ground-based telescopes, particularly the Extremely Large Telescope and Thirty Meter Telescope, will achieve the spatial resolution needed to actually image the largest nearby brown dwarfs as disks rather than points. This would allow direct mapping of atmospheric features rather than inferring them from brightness variations, revolutionizing the field.

Binary brown dwarf systems offer special opportunities. By comparing two objects in the same environment with slightly different masses or rotation rates, astronomers can isolate which factors drive specific atmospheric behaviors. More extensive monitoring of known binaries and discovery of new ones will build a comparative meteorology database.

Atmospheric modeling will grow increasingly sophisticated. As computing power increases, simulations can incorporate more complex chemistry, more realistic cloud microphysics, and three-dimensional dynamics at higher resolution. The iterative process between observations and models will converge on increasingly accurate understanding.

The connection to habitability, though indirect, matters for astrobiology. If we can understand weather patterns on brown dwarfs, we'll better understand potentially habitable exoplanets, particularly those in the "cold" regime where surface liquid water might exist. Brown dwarfs themselves aren't habitable, but the techniques developed to study them will inform the search for life elsewhere.

Some researchers even speculate about moons orbiting brown dwarfs. If a large moon orbited in the habitable zone of a relatively cool brown dwarf, could it support life? The tidal heating and radiation environment would be extreme, but not obviously impossible. Understanding brown dwarf atmospheres and energy output becomes relevant to assessing such exotic habitability scenarios.

Brown dwarfs occupy a unique niche in the universe, neither planet nor star, glowing faintly with their own heat while harboring some of the most violent weather imaginable. The storms raging across these failed stars, winds faster than bullets, clouds of vaporized rock, temperature swings that would destroy any spacecraft, remind us that the universe contains phenomena far more extreme than anything Earth experiences.

What makes brown dwarf meteorology compelling isn't just the extremes but what they reveal about atmospheric physics in regimes we can never access directly. Every observation, every brightness variation decoded, every cloud composition mapped, adds to our understanding of how atmospheres work across the full range of cosmic possibilities.

As telescopes improve and observations accumulate, the weather forecast for brown dwarfs grows clearer. We're learning to read the light from these distant objects like meteorologists read satellite images, inferring storm systems and atmospheric flows from subtle variations in infrared radiation. In doing so, we're not just studying failed stars. We're developing the tools and knowledge to understand planetary atmospheres throughout the galaxy, from hot Jupiters bathed in stellar radiation to potentially habitable worlds orbiting distant suns.

The universe's weather report, it turns out, is far stranger and more spectacular than we imagined. And brown dwarfs are teaching us how to read it.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.