Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: Cosmic supervoids are billion-light-year regions of near-empty space that actively shape the universe's evolution, from influencing galaxy formation to affecting cosmic microwave background radiation and providing crucial laboratories for studying dark energy and universal expansion.

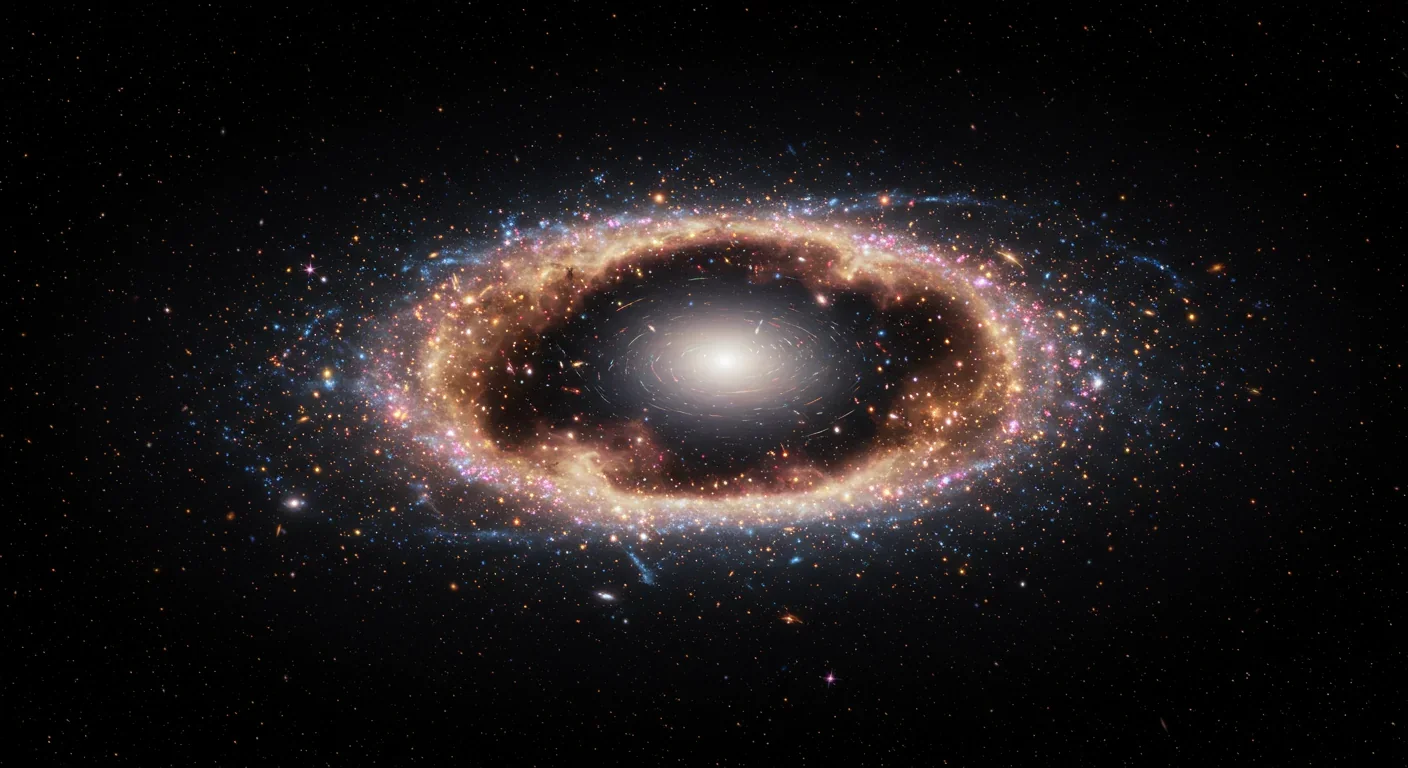

Imagine a region of space so vast and empty that it dwarfs entire galactic superclusters. A cosmic desert stretching more than a billion light-years across, containing just a handful of galaxies where thousands should exist. These aren't science fiction backdrops but real structures called supervoids, and they're rewriting our understanding of how the universe evolved and where it's headed. Far from being mere pockets of emptiness, these colossal voids actively shape the fabric of spacetime, influence the cosmic microwave background radiation we detect from the Big Bang, and offer crucial clues about dark energy's role in the universe's accelerating expansion. Scientists now realize that to understand the universe, we must understand its emptiest places.

Cosmic voids are vast regions of space containing significantly fewer galaxies than average. While the typical cosmic volume might host hundreds or thousands of galaxies, voids can harbor as few as 60 galaxies across hundreds of millions of light-years. The largest of these structures, called supervoids, can span over a billion light-years and contain densities as low as one-tenth the cosmic average.

The Boötes Void, discovered in 1981 by astronomer Robert Kirshner, exemplifies these cosmic deserts. Nicknamed the "Great Nothing," it stretches 330 million light-years in radius yet contains only 60 galaxies, compared to the 2,000 expected for a region that size. Its center lies approximately 700 million light-years from Earth, placing it well within observable range yet remaining profoundly empty.

Even more extreme is the Giant Void in Canes Venatici, measuring between 1 and 1.3 billion light-years across. Discovered in 1988, it ranks as the second-largest known void and demonstrates that emptiness operates at truly cosmic scales. Inside this vast underdense region, 17 galaxy clusters concentrate in a spherical zone just 50 megaparsecs across, creating an island of matter within an ocean of nothing.

What makes these voids remarkable isn't just their size but their density deficit. N-body simulations reveal that voids compose the majority of cosmic volume while containing only a small fraction of matter. This counterintuitive reality means the universe consists primarily of emptiness threaded with filaments of galaxies, like a cosmic web where the holes matter as much as the threads.

To grasp supervoids' significance, picture the universe as a three-dimensional sponge. Galaxy filaments form the solid material, densely packed with matter, while voids represent the air pockets. This structure, called the cosmic web, emerged from tiny density fluctuations in the early universe that gravity amplified over billions of years.

Structure formation theory explains that regions with slightly higher density attracted more matter through gravity, growing denser over time. These overdense regions became galaxy clusters and superclusters. Meanwhile, underdense regions lost matter to their denser neighbors, creating the voids. It's a process of gravitational segregation where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

But voids aren't perfectly empty. Most contain scattered galaxies, often arranged in curious patterns. The Boötes Void shows galaxies concentrated in a roughly cylindrical region piercing through its center, suggesting it formed through the coalescence of smaller voids. This hierarchical assembly mirrors how galaxies themselves build up from smaller structures.

The relationship between voids and filaments drives cosmic evolution. Matter flows from underdense to overdense regions like water draining from high ground to valleys. Researchers studying void dynamics have found that this drainage creates "density walls" at void boundaries where matter accumulates, forming the dense filaments that outline the cosmic web.

Understanding voids isn't just about mapping emptiness; it's about understanding how the universe organized itself from nearly uniform beginnings into the rich structure we observe today.

Supervoid formation begins with quantum fluctuations in the infant universe. During the Big Bang's first fractions of a second, microscopic variations in density were stretched to cosmic proportions by inflation. These variations became the seeds from which all structure grew.

In regions destined to become voids, initial density fell slightly below average. As the universe expanded and matter began clumping under gravity, these underdense zones had less material to work with. Nearby overdense regions gravitationally pulled matter away, causing the underdense zones to become even emptier. Over cosmic time, this feedback loop carved out vast voids.

The process accelerates because of dark energy. Under low densities, gravitational pull weakens; consequently, underdense regions expand at a rate exceeding mean cosmic expansion. Dark energy, which pushes space apart, amplifies this effect. Voids literally inflate faster than the universe around them, growing larger and emptier with time.

Recent research on void evolution reveals that voids provide pristine laboratories for studying cosmic processes. Because they contain so little matter, gravitational interactions remain minimal, allowing scientists to observe how dark energy acts on nearly empty space. These regions show us what the universe would look like if gravity's attractive force were almost entirely absent.

Computer simulations, such as the Millennium Simulation, model void formation across cosmic history. Results show that today's supervoids represent the culmination of 13.8 billion years of gravitational sorting, and they'll continue growing as dark energy increasingly dominates over gravity.

In 2004, astronomers analyzing the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the afterglow radiation from the Big Bang, discovered something strange: a cold spot about 10 times the size of the full moon appeared in the constellation Eridanus. The temperature difference was tiny, around 70 microkelvins below the surrounding sky, but statistically improbable enough to spark intense investigation.

Theories proliferated wildly. Some speculated it might represent evidence of a parallel universe colliding with ours during inflation. Others suggested exotic physics from the universe's first moments. The cold spot became one of cosmology's most intriguing anomalies.

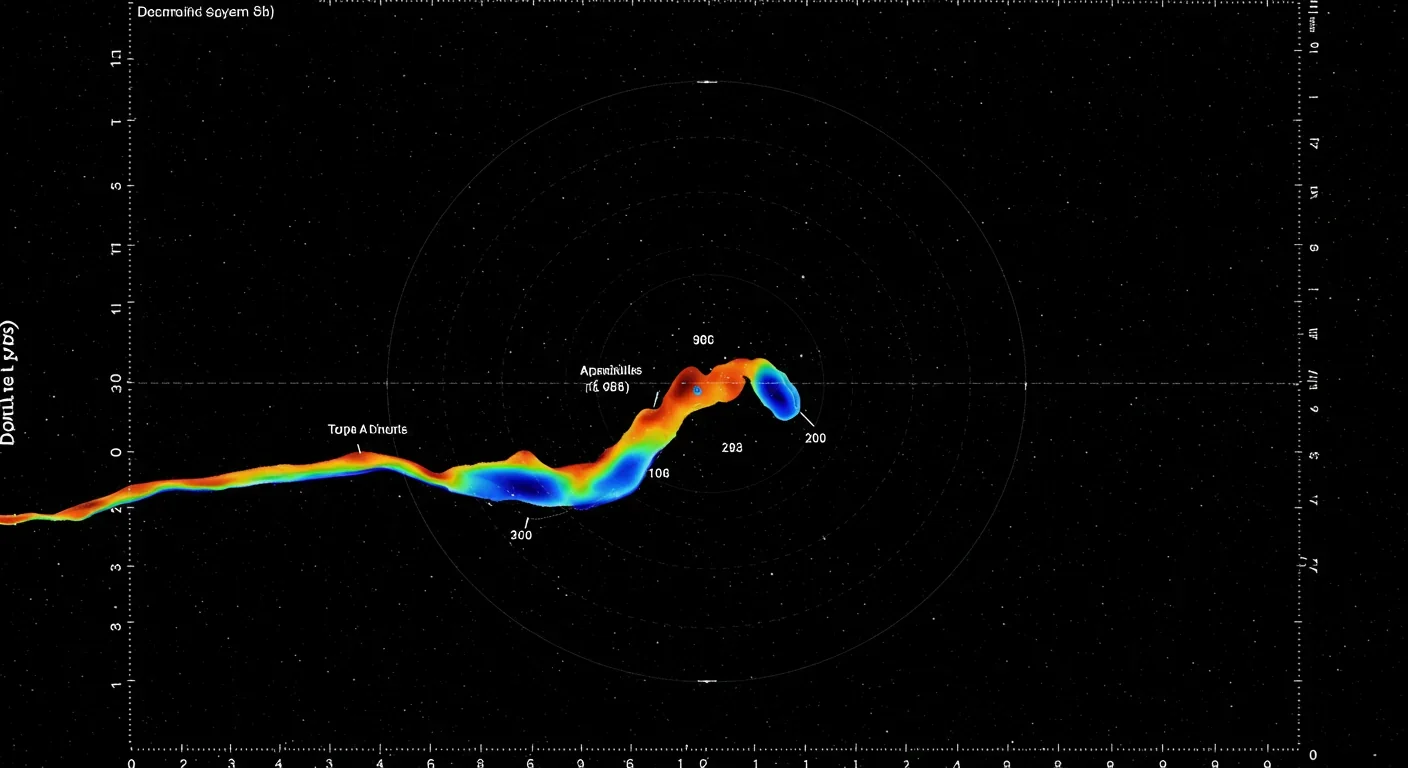

Then in 2015, astronomers led by Istvan Szapudi found a compelling explanation: a supervoid. Using infrared data from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) matched with visible-light observations from Pan-STARRS1, they constructed a tomographic map of galaxy distribution. The map revealed a massive void stretching 1.8 billion light-years across, positioned directly behind the cold spot and existing when the universe was 11.1 billion years old.

This supervoid explains the temperature anomaly through the Integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect (ISW). When CMB photons pass through a void, they lose energy climbing out of the shallow gravitational potential well. Normally they'd regain that energy falling into the next overdense region. But because the universe is expanding and dark energy is pushing voids to grow larger, the void has expanded by the time photons exit, so they can't fully recover their lost energy. The result: photons arrive at Earth slightly cooler, creating the cold spot.

"The dip in the numbers of galaxies in the centre of the cold spot signaled the presence of the largest known structure in the universe - a supervoid stretching 1.8 billion light years across the sky."

- Istvan Szapudi, University of Hawaii

The discovery validated that exotic physics weren't needed. The cold spot arose from well-understood processes within the standard Lambda-CDM cosmological model. However, questions remain. The probability of such a large void aligning with a cold spot by chance is small, though not impossible. Some researchers continue investigating whether additional factors might be at play.

Recent discoveries suggest supervoids might help resolve one of cosmology's most pressing problems: the Hubble tension. Measurements of the universe's expansion rate yield different results depending on the method used. Observations of distant supernovae and the CMB give one value, while measurements of nearby Cepheid variable stars give another, higher value. The discrepancy has persisted despite increasingly precise observations.

Enter the KBC void, a proposed supervoid centered roughly on the Milky Way. Some astronomers suggest we reside in a region of space with below-average density extending several hundred million light-years. If true, this local underdensity would affect how we measure cosmic expansion.

A new approach published in 2024 uses the observed local supervoid to potentially give the universe's expansion an extra push. The idea is that if we're in a void, local measurements of expansion would be higher than the cosmic average because voids expand faster due to their lower gravitational pull. This could reconcile the conflicting measurements.

The hypothesis remains controversial. Some cosmologists argue the KBC void's existence is uncertain, and even if it exists, whether it's large enough to explain the Hubble tension. Others point out that testing the KBC void hypothesis requires careful analysis of galaxy distributions in multiple directions.

Astrophysicist Avi Loeb has suggested that voids growing under dark energy's influence might provide crucial tests of dark energy models. If we can precisely measure void expansion rates, we might distinguish between different theories of what dark energy actually is. Supervoids thus become laboratories for fundamental physics.

The possibility that we inhabit a supervoid carries profound implications: our measurements of cosmic expansion might not represent the universe as a whole, requiring us to rethink how we extrapolate local observations to universal conclusions.

Finding cosmic voids presents a unique challenge. You can't directly image emptiness. Instead, astronomers use redshift surveys, measuring how light from galaxies stretches as the universe expands. Redshift indicates distance, allowing researchers to create three-dimensional maps of galaxy positions.

When analyzing these maps, voids appear as regions with abnormally few galaxies. Statistical techniques identify underdense zones by comparing local galaxy counts to cosmic averages. The larger and emptier the void, the easier it becomes to detect, though even prominent voids like Boötes remained hidden until systematic surveys revealed them.

Modern surveys have revolutionized void science. The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), currently conducting a massive galaxy survey, enables unprecedented void mapping. By measuring millions of galaxy redshifts, DESI constructs detailed three-dimensional maps showing void shapes, sizes, and internal structure.

Advanced techniques using quasars extend void detection to higher redshifts, tracing cosmic web evolution across billions of years. The Quaia catalogue identifies voids and clusters in the quasar distribution, revealing how large-scale structure developed when the universe was younger.

Gravitational lensing provides another detection method. When light from distant galaxies passes through or near a void, the void's weak gravitational field subtly deflects it. Analysis of Planck satellite data has detected void signatures in the CMB's gravitational lensing pattern, confirming voids' large-scale impact on light propagation.

Computer simulations now produce fast void catalogs, allowing researchers to compare observed voids with theoretical predictions. These tools help determine whether observed void populations match what standard cosmology predicts or if anomalies suggest new physics.

Recent work has probed cosmic voids using emission-line galaxies, exploiting how certain galaxy types trace underdense regions. This technique reveals void galaxies' properties and how their evolution differs from galaxies in denser environments.

Intriguing recent research has identified "cosmic tunnels" connecting adjacent voids. These structures, essentially low-density channels between voids, may affect the Integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect in unexpected ways. When CMB photons travel through these tunnels rather than through denser regions, they experience different gravitational environments, potentially creating additional temperature patterns.

The study of cosmic tunnels suggests the cosmic web's structure is more intricate than simple void-and-filament models indicate. Tunnels might facilitate matter flow between voids or represent regions where multiple voids merged during formation. Understanding these connections could reveal how voids communicate and influence each other across cosmic distances.

Researchers have created comprehensive lists of known voids, cataloging dozens of large underdense regions. Notable examples include the Local Void, a relatively nearby underdense region that influences our cosmic neighborhood, and multiple supervoids identified through various surveys.

The distribution of voids themselves shows patterns. Voids tend to avoid other voids at very large scales but also avoid the densest clusters. They occupy an intermediate zone in the cosmic web, creating a hierarchical structure where voids of various sizes nest within larger patterns.

Perhaps supervoids' most important role is as dark energy laboratories. Dark energy constitutes about 68% of the universe's total energy but remains poorly understood. We know it drives accelerating cosmic expansion, but its nature remains mysterious.

Voids offer pristine environments for studying dark energy because matter density there is so low that gravitational effects are minimized. Any accelerated expansion we observe in voids can be more confidently attributed to dark energy rather than complex gravitational dynamics.

Studies of void expansion rates have used void statistics from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey to constrain cosmological parameters. By measuring how fast voids grow and comparing this to theoretical predictions, researchers narrow down possible dark energy models.

Different dark energy theories predict different void evolution. If dark energy is Einstein's cosmological constant (a fixed energy density of space itself), voids should expand at a predictable rate. If dark energy varies over time or space, void expansion should show corresponding variations. So far, observations support the constant dark energy model, but precision measurements continue refining our understanding.

"Understanding how dark energy behaves in the universe's emptiest regions helps us determine whether it truly represents a fundamental property of space itself or something more exotic."

- Cosmologists studying void dynamics

Some physicists have proposed that studying how dark energy "blows up" voids could distinguish between competing theories. If dark energy interacts with matter or varies across space, these effects should be most apparent in regions where matter is nearly absent.

Life inside a void differs dramatically from life in a cosmic metropolis. Void galaxies experience less gravitational interaction, fewer mergers, and different evolutionary paths than galaxies in denser environments. Research on pristine evolution in voids shows these galaxies evolve more slowly and retain more of their original characteristics.

This isolation makes void galaxies valuable for understanding how galaxies would develop without constant external disturbances. In dense environments, galaxy mergers, tidal interactions, and gas stripping dramatically alter galactic properties. Void galaxies largely avoid these complications, providing cleaner laboratories for testing galaxy formation theories.

Interestingly, void galaxies aren't uniformly distributed within voids. Many concentrate near void walls where they can still access some inflowing gas. The very centers of large voids often remain entirely devoid of galaxies, creating truly empty regions spanning tens or hundreds of millions of light-years.

Galaxy surveys targeting void regions have revealed that void galaxies tend to be smaller, bluer, and more gas-rich than average. They form stars at steadier rates without the bursts triggered by mergers common in denser areas. This gentler evolution preserves information about galactic youth that more disturbed galaxies have erased.

The existence and properties of supervoids provide critical tests of cosmological theories. The Lambda-CDM model, which describes the universe's composition as about 68% dark energy, 27% dark matter, and 5% ordinary matter, predicts specific void properties. Observed voids must match these predictions, or the model needs revision.

So far, void observations broadly support Lambda-CDM. Studies confirm that structures like the Boötes Void don't conflict with standard cosmology. The void population's size distribution, density profiles, and evolution over cosmic time all align with simulations based on Lambda-CDM physics.

However, some anomalies persist. The KBC void, if confirmed, might be larger than Lambda-CDM readily predicts, though statistical uncertainties remain. The cold spot supervoid, while explaining the CMB anomaly, sits at the edge of what's expected from random chance. These edge cases drive continued research.

Voids also constrain alternative gravity theories. Models that modify gravity to explain dark energy make different predictions about void growth. By comparing observed void expansion to predictions from modified gravity versus Lambda-CDM, researchers test which better describes reality. Current evidence favors standard general relativity with dark energy, but void studies continue refining these tests.

The universe's story isn't just about what exists but about what doesn't exist: the empty spaces that define and shape everything else.

Next-generation surveys will revolutionize void science. The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument will map tens of millions of galaxies, creating the most detailed void catalog ever. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, beginning operations soon, will survey the entire visible sky repeatedly, identifying voids across a vast volume of space and cosmic time.

These surveys will enable statistical studies impossible today. Researchers will measure how void properties vary with cosmic epoch, tracking their growth from the early universe to the present. This evolution encodes information about dark energy's history and nature.

Advanced simulation techniques now allow rapid generation of synthetic void catalogs. By running thousands of simulations with slightly different cosmological parameters, scientists can determine which parameters best match observed void populations. This approach turns voids into precision cosmological probes.

Future research will also investigate void substructure in greater detail. How do small voids merge into supervoids? What governs tunnel formation between voids? Do voids contain dark matter halos too small to host galaxies? Answering these questions will complete our understanding of cosmic structure.

Machine learning is transforming void identification. Neural networks can analyze galaxy distributions, automatically identifying voids and measuring their properties with unprecedented speed and accuracy. These tools will process the enormous datasets from upcoming surveys, finding subtle patterns human astronomers might miss.

The paradox of cosmic voids is that studying nothingness reveals so much. These vast empty regions aren't cosmic accidents but fundamental components of universal architecture. They show us how gravity and dark energy compete, how structure emerged from uniformity, and how the universe will evolve billions of years hence.

Supervoids embody the universe's large-scale fate. As dark energy increasingly dominates over gravity, cosmic expansion accelerates. Galaxy clusters will remain gravitationally bound, but the voids between them will grow ever larger. In the far future, the universe will become a collection of isolated island clusters separated by voids so vast that light from one island can never reach another. Our descendants, if any, will inhabit a universe of islands in an ever-expanding ocean of nothing.

This cosmic geography affects not just galaxies but the fundamental structure of spacetime itself. Voids' accelerated expansion means spacetime there differs subtly from denser regions. Some physicists speculate that if dark energy varies with density, voids and dense regions could develop different physical properties, creating a universe more varied than currently imagined.

"The universe's story isn't just about what exists but about what doesn't exist: the empty spaces that define and shape everything else."

- Modern Cosmological Perspective

Understanding voids also provides perspective on humanity's cosmic address. We don't live in a typical cosmic environment. The Milky Way resides in a moderately dense region, not in a void and not in a dense cluster. If the KBC void hypothesis proves correct, we might live in a transitional zone between typical density and underdensity. Our cosmic location thus shapes what we observe and potentially biases our cosmological measurements.

Perhaps most fundamentally, supervoids inspire awe at the universe's scale. A billion light-years is almost incomprehensible. Light traveling at 186,000 miles per second takes a billion years to cross these voids. If you could somehow travel at light speed, starting when multicellular life first appeared on Earth, you'd only now be traversing the largest supervoids.

These structures dwarf not just human scales but galactic ones. The Milky Way, our home containing hundreds of billions of stars, spans about 100,000 light-years. A supervoid is ten thousand times wider. Place the Milky Way at a supervoid's edge and fly across at the speed of light for a million years; you'd still have most of the journey ahead.

Yet despite their size, supervoids formed through the same physical processes governing falling apples and planetary orbits: gravity, described by Einstein's equations over a century ago. The universe's simplicity at cosmic scales - where gravity and expansion dominate - allows structures of almost unimaginable size to emerge from elegant physical laws.

Cosmic voids and supervoids challenge us to rethink what matters in the universe. For centuries, astronomy focused on bright objects: stars, galaxies, clusters. We catalogued what we could see, assuming empty space was merely backdrop. Supervoids reveal this assumption was backwards.

The universe's architecture arises as much from emptiness as from matter. Voids aren't passive gaps but active participants in cosmic evolution, influencing galaxy formation, CMB patterns, and possibly our measurements of universal expansion. They provide laboratories for studying dark energy, the mysterious force that will determine the universe's ultimate fate.

As we map the cosmic web in ever-greater detail, supervoids emerge not as inconsequential absences but as essential structures encoding the universe's history and future. They remind us that understanding the cosmos requires embracing both the spectacular and the subtle, both what exists and what conspicuously doesn't.

The next time you look at the night sky, remember: between every visible point of light stretch unimaginable distances, many encompassed by voids where galaxies are rare and space expands faster than average. These billion-light-year deserts, invisible yet immense, are as much a part of cosmic reality as the blazing galaxies that capture our attention. In learning to see the universe's emptiness, we've discovered it's far from empty - it's full of profound implications about reality itself.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.