Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

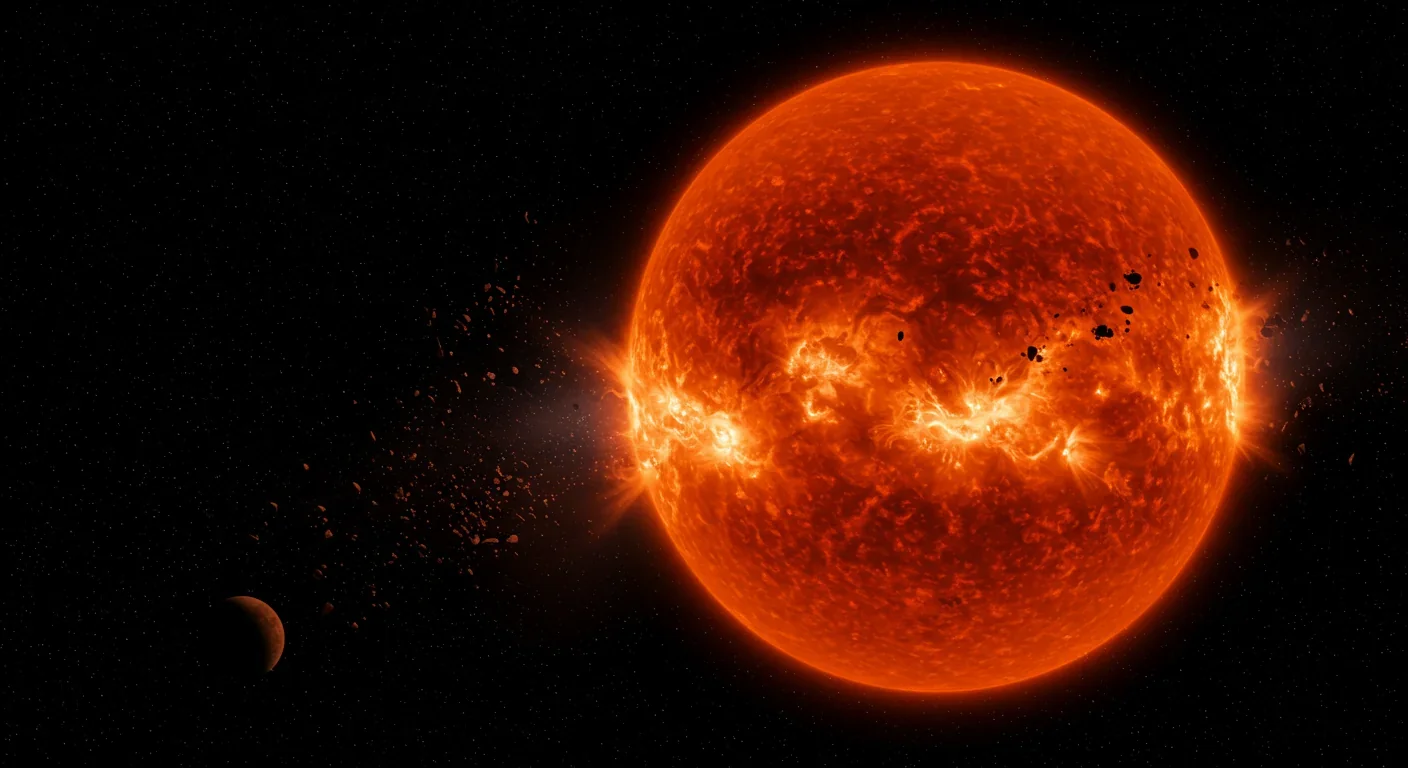

TL;DR: Dying stars create every heavy element through two processes: the rapid r-process in explosive neutron star collisions and supernovae, and the slow s-process in aging red giants. The gold in jewelry, uranium in reactors, and platinum in cars all originated in stellar death throes billions of years ago.

Hold the gold ring on your finger up to the light. That precious metal wasn't forged on Earth - it was born in the violent death throes of stars billions of years ago. The platinum in your car's catalytic converter? Same story. The uranium powering nuclear reactors? Created in cosmic explosions so intense they briefly outshine entire galaxies. Every heavy element in existence - from the gold in Fort Knox to the thorium in nuclear fuel - originated in stellar furnaces operating at temperatures that would vaporize planets.

The universe started simple. After the Big Bang, only hydrogen, helium, and traces of lithium existed. Everything else - all 90+ natural elements - had to be built atom by atom inside stars. While living stars can fuse lighter elements up to iron through standard nuclear fusion, creating anything heavier requires conditions so extreme that only dying stars can provide them. This is where the cosmic story gets fascinating, because it turns out there are two distinct assembly lines for heavy elements, each operating under radically different conditions.

Iron-56 sits at a special place in the periodic table - it represents nature's most stable nucleus. Inside a star's core, fusion reactions march steadily up the periodic table, combining lighter elements into heavier ones and releasing tremendous energy in the process. Hydrogen fuses into helium. Helium fuses into carbon and oxygen. The chain continues through neon, magnesium, silicon, and sulfur.

Then it hits iron, and everything changes.

Iron-56 has the highest binding energy per nucleon of any element in existence. This means its nucleus is locked together more tightly than any other. To understand why this matters, consider that fusion releases energy by taking lighter, loosely-bound nuclei and creating tighter, more stable ones. The mass difference gets converted to energy through Einstein's famous E=mc² equation.

But iron-56 is already at the peak. Fusing iron nuclei together doesn't release energy - it consumes it. When a massive star's core fills with iron, fusion grinding to a halt. The core suddenly has no energy source supporting it against gravity's crushing force. Within seconds, catastrophe follows. The core collapses, temperatures spike to billions of degrees, and the star explodes as a supernova. The blast is so violent that it can briefly outshine an entire galaxy of 100 billion stars.

When a massive star's iron core collapses, it releases more energy in seconds than our sun will produce in its entire 10-billion-year lifetime. This is where the universe forges its heaviest elements.

This is where heavy element creation begins.

The r-process - short for rapid neutron-capture process - is nature's most extreme manufacturing technique. It requires conditions so harsh that scientists debated for decades about where it could possibly occur. The process demands neutron densities around 10²⁴ free neutrons per cubic centimeter at temperatures exceeding one billion degrees Kelvin.

Here's how it works: Take an iron nucleus and bombard it with neutrons at an insane rate. In normal stellar conditions, a nucleus might capture a neutron every few years. During the r-process, nuclei capture multiple neutrons in milliseconds, often absorbing dozens before they have time to radioactively decay. The nuclei balloon with extra neutrons, becoming wildly unstable isotopes that would never exist under normal circumstances.

Then, when the neutron bombardment ends, these bloated nuclei undergo a cascade of beta decays, transforming excess neutrons into protons and marching up the periodic table. A single seed nucleus of iron can climb all the way to uranium and beyond through this process, passing through every heavy element along the way.

But where does this happen? For generations, core-collapse supernovae seemed like the obvious answer. When a massive star explodes, the outer layers encounter a shock wave propagating outward from the collapsed core. Behind this shock, temperatures and neutron densities might reach r-process conditions. Computer models showed it was theoretically possible.

Yet something didn't add up. Observations of the cosmic abundance of heavy elements suggested that supernovae alone couldn't account for all the gold, platinum, and uranium in the universe. Scientists needed another source - something even more violent than a supernova.

On August 17, 2017, gravitational wave detectors recorded something extraordinary: two neutron stars colliding 130 million light-years away. The event, designated GW170817, was immediately followed by a burst of light across the electromagnetic spectrum. Telescopes worldwide swiveled to observe the aftermath.

What they saw changed everything. Spectroscopic analysis revealed the unmistakable signatures of freshly synthesized heavy elements - strontium, gold, platinum, and lanthanides - glowing in the expanding debris. The collision had created a "kilonova," an explosion powered by the radioactive decay of r-process elements.

"The 2017 neutron star merger was a Rosetta Stone for understanding heavy element creation. For the first time, we watched gold being made in real time."

- Astrophysics Research, GW170817 Discovery

Neutron stars are the crushed cores of dead massive stars, packing more mass than our sun into a sphere just 20 kilometers across. Their interiors contain matter at densities beyond anything we can create in laboratories - a sugar cube of neutron star material would weigh a billion tons. When two of these objects spiral together and merge, they create the ultimate neutron factory.

The collision ejects a fraction of a solar mass worth of neutron-rich material into space. This debris is so packed with neutrons that r-process nucleosynthesis proceeds explosively. Within seconds, iron-group elements transmute into gold, platinum, uranium, and every other heavy element. A single neutron star merger produces roughly 100 Earth masses of pure gold - far more than exists in our entire planet's crust.

The 2017 observation confirmed that neutron star mergers are a primary source of r-process elements, though recent research suggests additional sources may also contribute significantly to the galactic inventory of heavy elements.

Just when astronomers thought they understood heavy element production, another surprise emerged. In 2024, researchers analyzing high-energy astrophysical events identified magnetar flares as a previously unrecognized source of r-process elements.

Magnetars are neutron stars with magnetic fields a thousand trillion times stronger than Earth's. Occasionally, these fields become unstable and snap, releasing tremendous energy in massive flares. The strongest flares eject neutron-rich material that can undergo r-process nucleosynthesis.

This discovery helps explain puzzling observations of heavy element abundances in ancient stars that couldn't be accounted for by neutron star mergers alone. The universe appears to have multiple pathways for creating precious metals and radioactive elements, ensuring these materials get distributed throughout galaxies.

While the r-process operates in seconds during catastrophic explosions, nature has another, more patient method for building heavy elements. The s-process - slow neutron-capture process - occurs in aging red giant stars called asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars.

These stars have exhausted the hydrogen in their cores and now burn helium in shells around an inert carbon-oxygen core. Occasionally, the helium shell undergoes a thermal pulse, briefly releasing enormous energy. During these pulses, conditions become just right for the s-process to operate.

The mechanism is gentler than the r-process. An iron nucleus captures a neutron about once every 10-100 years. That's slow enough that after each capture, the nucleus typically decays before the next neutron arrives. Instead of racing up the periodic table through unstable isotopes like the r-process, the s-process follows a more stable path, creating roughly half of the elements heavier than iron.

The s-process operates over thousands of years in aging stars, while the r-process completes in milliseconds during cosmic explosions. Both pathways are essential for creating the full diversity of heavy elements in the universe.

The s-process is particularly good at producing elements like strontium, barium, and lead. It creates many of the same elements as the r-process but in different proportions and through different isotopes. Elements that can only be made by the r-process - like most isotopes of platinum, gold, thorium, and uranium - don't form efficiently through the slow route.

As AGB stars age, convection currents dredge material from deep layers where the s-process operates up to the surface. The star then sheds its outer layers in stellar winds, dispersing the newly created elements into space. Presolar silicon carbide grains found in meteorites preserve direct samples of s-process material from long-dead AGB stars, giving us a tangible connection to ancient stellar forges.

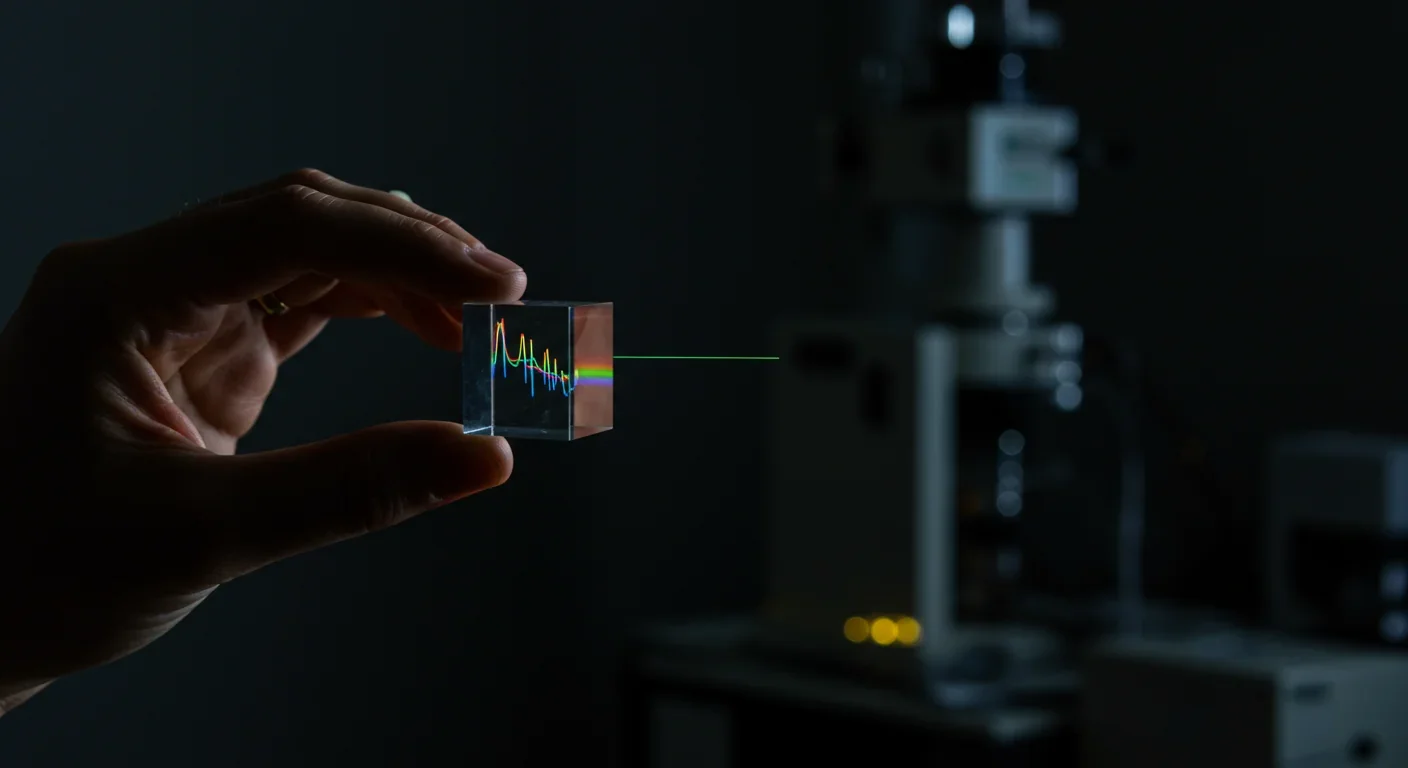

How do we know all this? Astronomers have developed sophisticated techniques for reading the chemical fingerprints of stars. Every element absorbs and emits light at characteristic wavelengths. By spreading starlight into a spectrum, astronomers can identify which elements are present and in what quantities.

This spectroscopy has revealed ancient stars - some nearly as old as the universe itself - with distinctive patterns of heavy elements. Metal-poor stars with enhanced r-process elements tell us that r-process events happened very early in cosmic history. The specific ratios of different elements constrain models of neutron star mergers and supernova explosions.

In some cases, astronomers have found stars with anomalous abundances that challenge our understanding. These outliers push scientists to refine models and consider additional sources of heavy elements. Each new observation either confirms existing theories or demands new explanations.

The heavy elements created by dying stars don't stay isolated. Supernova explosions scatter material across vast regions of space, enriching the interstellar medium. Over billions of years, this enriched gas condenses into new generations of stars, planets, and - at least once - living beings.

Our solar system formed 4.6 billion years ago from a cloud that had been enriched by countless stellar generations. The r-process and s-process elements in that cloud became incorporated into planets, asteroids, and comets. On Earth, geological processes then concentrated valuable elements into mineable deposits.

The galactic chemical evolution follows predictable patterns. Early in cosmic history, the universe contained only hydrogen and helium. The first generation of massive stars lived and died quickly, seeding space with the first heavy elements. Each subsequent generation built on this foundation, gradually increasing the metallicity of the cosmos.

Different regions of galaxies show different enrichment patterns depending on their star formation history and the frequency of neutron star mergers. By studying these variations, astronomers can reconstruct the assembly history of galaxies and understand how different stellar processes contributed to the periodic table we know today.

Every technological civilization depends on heavy elements created in dying stars. The gold in electronics, needed for corrosion-resistant connections, came from neutron star collisions billions of years ago. Platinum catalysts that reduce automotive emissions trace their origin to stellar cataclysms. The uranium and thorium powering nuclear reactors are r-process elements that can only form under the most extreme conditions in the universe.

"The gold in your jewelry, the uranium in nuclear reactors, the platinum in catalytic converters - every atom was forged in the death throes of stars that lived and died before our sun was born."

- Stellar Nucleosynthesis Research

Even biologically, we're connected to these cosmic forges. Many trace elements essential for life - zinc, copper, selenium, iodine - were synthesized in stellar environments. The iron in hemoglobin, carrying oxygen through our blood, might have formed through normal stellar fusion, but the molybdenum in certain enzymes required neutron-capture processes.

Understanding stellar nucleosynthesis has practical implications beyond satisfying curiosity. By studying how rotating proto-magnetar winds produce heavy elements, scientists gain insights into exotic physics that can't be replicated in laboratories. The extreme conditions during the r-process involve nuclear reactions between unstable isotopes that we can barely study on Earth.

The 2017 neutron star merger opened a new era of multi-messenger astronomy - combining gravitational waves with electromagnetic observations to study cosmic events. As gravitational wave detectors improve, astronomers expect to observe many more neutron star mergers, refining our understanding of r-process nucleosynthesis.

Meanwhile, spectroscopic surveys are cataloging heavy element abundances in millions of stars, mapping the chemical evolution of our galaxy in unprecedented detail. These observations test theoretical models and reveal how efficiently different stellar processes contribute to heavy element production.

New telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope can observe the earliest generations of galaxies, potentially detecting the signatures of the first heavy element production events. Understanding when and how quickly heavy elements appeared shapes our picture of how habitable planets formed and whether life could emerge in different cosmic eras.

Perhaps the most profound implication of stellar nucleosynthesis is what it reveals about our connection to the cosmos. The atoms in our bodies, the minerals in Earth's crust, the precious metals we value - all originated in stars that died before our sun even formed.

We're literally made of stardust, but not just any stardust. The heavy elements that make technological civilization possible come specifically from dying massive stars - from core-collapse supernovae, neutron star mergers, magnetar flares, and the slow cooking of elements in red giants.

These stellar forges operated for billions of years before Earth existed, building up the periodic table one neutron capture at a time. The r-process created radioactive elements that now help heat Earth's interior, driving plate tectonics and maintaining our magnetic field. The s-process created the heavy elements that add complexity to chemistry and enable advanced materials.

Every atom heavier than iron in your body was created in a dying star. You're not just made of stardust - you're made of supernova debris, neutron star collision remnants, and the patient work of red giant stars over billions of years.

Every gold ring, every platinum watch, every tungsten light bulb filament connects us to cosmic violence that occurred eons ago and light-years away. The fact that we can trace these connections - that we understand the nuclear physics of how iron transforms into gold and why certain stars build lead - represents one of humanity's most remarkable intellectual achievements.

The universe started with almost nothing. Through the patient work of stellar nucleosynthesis, cycling through generations of stars over billions of years, it created the rich chemical diversity that makes planets, life, and consciousness possible. We're not just observers of this cosmic story - we're participants, built from the ashes of dead stars, contemplating the very processes that created us.

That gold ring on your finger? It's not just metal. It's a fragment of a neutron star collision that happened when the universe was young. It's nuclear alchemy performed under conditions we can barely imagine, preserved through billions of years, refined by geological processes, and shaped by human hands into something beautiful. Every heavy element tells a similar story - a tale of cosmic violence, nuclear physics, and the long chain of events that transformed a simple, hydrogen-filled universe into one complex enough to create creatures capable of understanding their own origins.

The cosmic forge never stops. Right now, somewhere in the universe, stars are dying, neutron stars are colliding, and heavy elements are being born. The raw materials for future planets, future life, and future stories are being created in stellar explosions we may someday detect. The universe continues its grand project of chemical evolution, building complexity from simplicity, turning hydrogen into gold, one stellar death at a time.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.