DAVINCI: NASA's Probe Will Survive Venus's Crushing Heat

TL;DR: Triton, Neptune's largest moon, orbits backward at 4.39 km/s. Captured from the Kuiper Belt, tidal forces now pull it toward destruction in 3.6 billion years.

Imagine a moon the size of Pluto, racing backward around an ice giant at 4.39 kilometers per second, caught in a gravitational death spiral that won't reach its spectacular conclusion for another 3.6 billion years. This isn't science fiction - it's the real-life story of Triton, Neptune's largest moon, and one of the most bizarre objects in our solar system. While most moons obediently circle their planets in the same direction the planet rotates, Triton does the opposite, orbiting Neptune retrograde in a cosmic middle finger to conventional physics. This backward dance isn't just strange, it's a death sentence, and understanding why reveals profound insights into planetary formation, gravitational mechanics, and the violent history of our solar system's outer reaches.

When William Lassell discovered Triton just 17 days after Neptune itself was found in 1846, astronomers immediately noticed something odd. Among all the large moons in the solar system, Triton stands alone as the only substantial moon with a retrograde orbit. It's not just traveling backward - it's doing so at a blistering 4.39 km/s, completing one orbit around Neptune every 5.87 days while rotating in perfect synchrony, always showing the same face to its planet like our own Moon does to Earth.

The scale of Triton's rebellion becomes clear when you consider its size. At 2,710 kilometers in diameter - roughly the distance from London to Moscow - Triton is the seventh-largest moon in the entire solar system, bigger even than Pluto. For comparison, that makes it larger than any of the dwarf planets except Eris, and more massive than all the known smaller objects in the solar system combined. A moon this large orbiting backward isn't just unusual, it's practically impossible under normal circumstances.

So how did Triton end up in this predicament? The answer lies not around Neptune, but in the frozen wasteland beyond: the Kuiper Belt.

Astronomers are now convinced that Triton wasn't born around Neptune at all. Instead, it was a free-flying Kuiper Belt Object, one of thousands of icy worlds orbiting in the cold darkness beyond Neptune's orbit, until a chance encounter changed everything. Between 4.5 and 4 billion years ago, during the solar system's chaotic youth, Triton wandered too close to Neptune and was captured by the ice giant's powerful gravity.

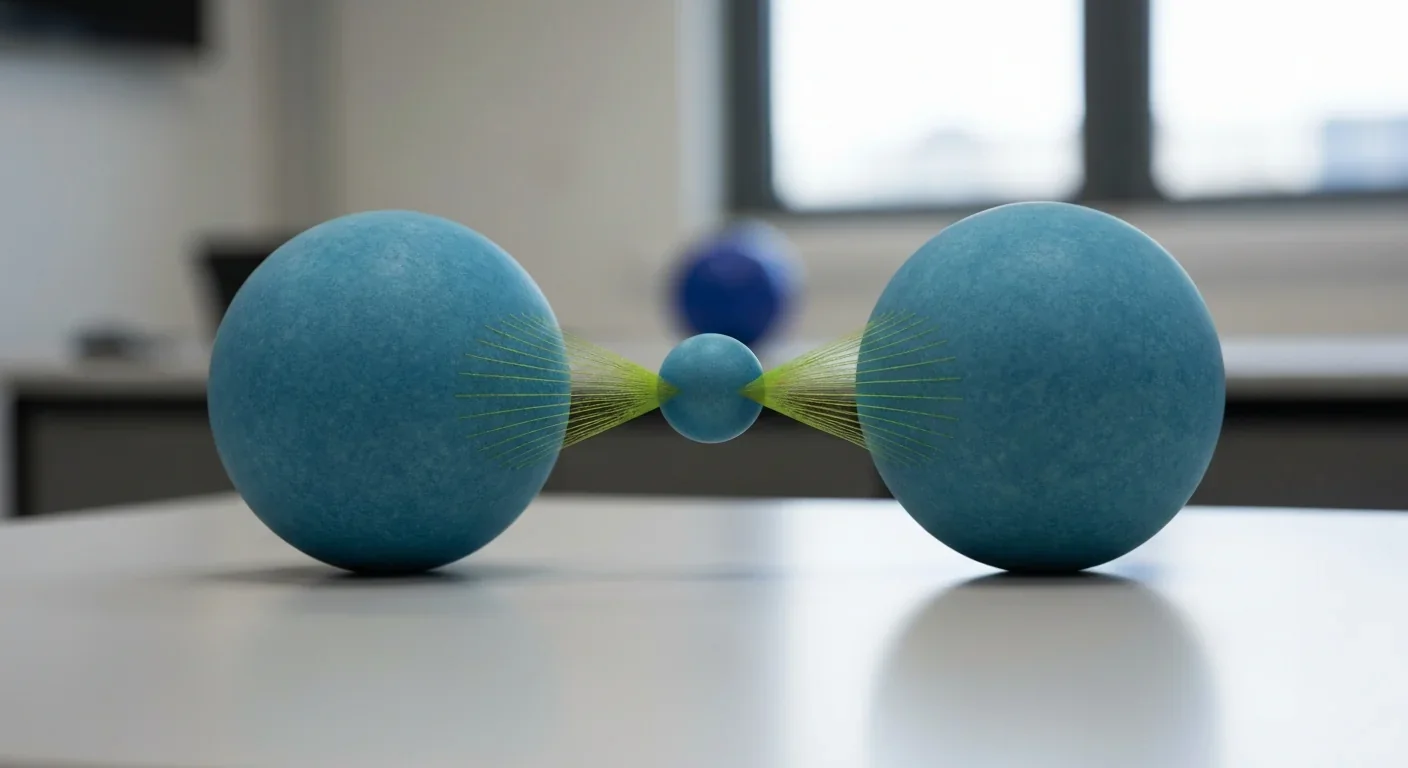

But gravitational capture isn't as simple as it sounds. When you do the orbital mechanics math, capturing an object as massive as Triton presents serious problems. A lone object passing by a planet gains speed as it approaches, then loses that same speed as it recedes - meaning it should just fly past and escape back into space. For capture to occur, something needs to steal energy from the incoming object at just the right moment.

When a binary pair of Kuiper Belt objects encounters a massive planet, the planet's gravity can tear the pair apart, capturing one while ejecting the other. This three-body interaction solves the energy problem that makes capturing large objects so difficult.

The most likely scenario, according to research from UC Santa Cruz, is that Triton wasn't alone. It probably traveled through the early solar system as part of a binary pair - two Kuiper Belt objects orbiting each other, like Pluto and its large moon Charon do today. When this pair encountered Neptune, the planet's gravity tore them apart in a three-body interaction, capturing one object (Triton) while flinging its companion out into the void. The energy required to capture Triton came from breaking up the binary system.

This violent capture explains Triton's retrograde orbit. The direction of Triton's orbit depends entirely on the trajectory it happened to be following when it was captured - it had nothing to do with the direction Neptune was rotating or the way the planet's other moons orbit. It's like catching a ball thrown from a random direction; the ball doesn't care which way you're spinning.

How confident are scientists in this capture scenario? The evidence is overwhelming. First, there's Triton's composition. The moon is remarkably similar to Pluto and other Kuiper Belt objects, with a density suggesting it's about 25% water ice and 75% rock. Its surface is dominated by frozen nitrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide - exactly the volatile ices you'd expect on a Kuiper Belt object that formed in the frigid outer solar system.

Then there's the orbital evidence. Triton's orbit is now nearly circular and aligned with Neptune's equator, but that's only because billions of years of tidal forces have gradually circularized and aligned it. Computer simulations show that a captured object would initially have a highly elliptical and tilted orbit, which would then slowly evolve into Triton's current configuration over hundreds of millions of years. The orbit we see today is exactly what you'd expect from a captured object after 4 billion years of tidal evolution.

The smoking gun comes from Neptune's other moons. Neptune has 14 known moons, but except for Triton, they're all tiny - the second-largest, Proteus, is only 420 kilometers across. Where did all of Neptune's original large moons go? The answer: Triton destroyed them. When Triton was first captured on its wild, elliptical orbit, it would have carved through Neptune's existing moon system like a wrecking ball through a house. Gravitational interactions would have ejected some moons and sent others crashing into Neptune or into each other. The small moons we see today are either fragments from these collisions or asteroids captured later, after Triton's orbit had settled down.

"Triton is remarkably similar in composition to Pluto, with surface temperatures averaging -235°C making it one of the coldest objects measured in our solar system. Yet it shows signs of past geological activity, suggesting a violent and energetic capture process."

- Voyager 2 Mission Data, NASA

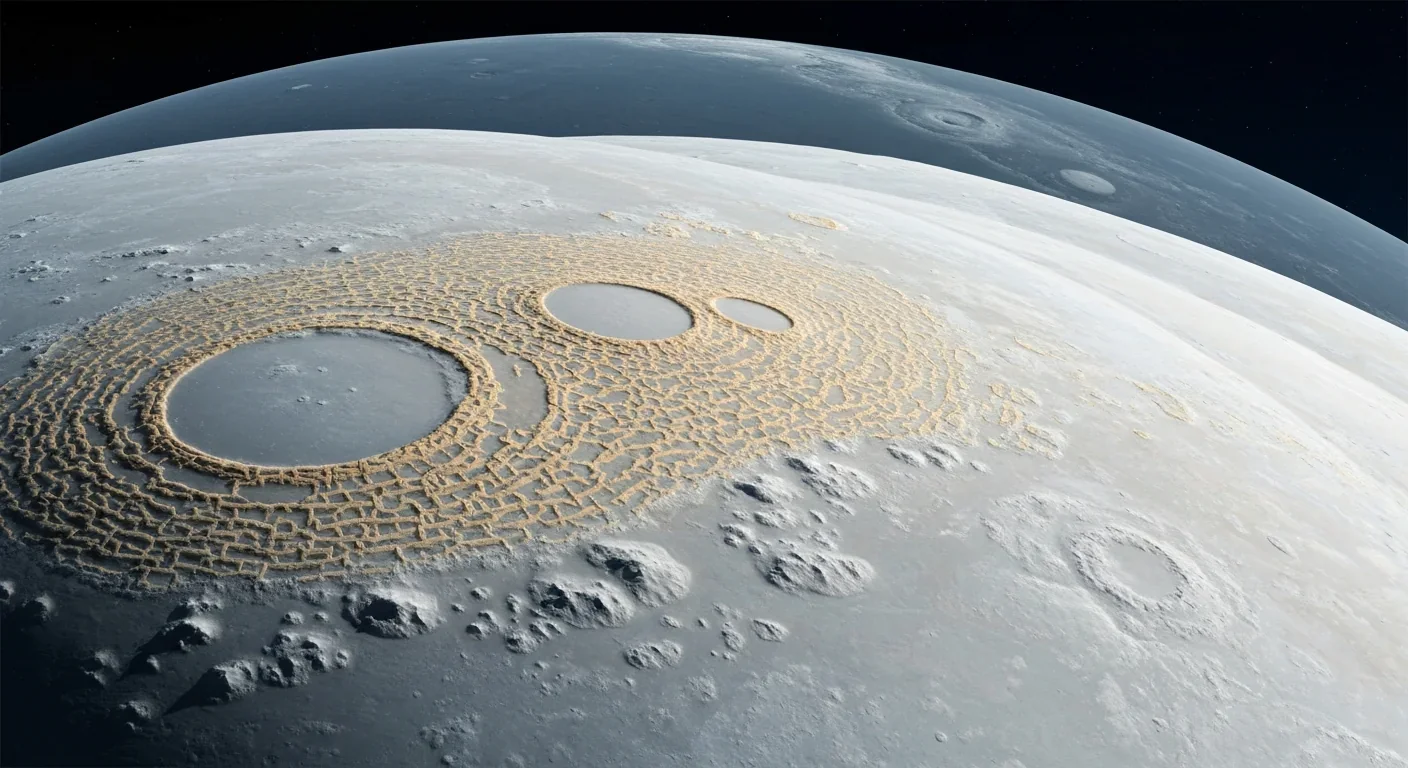

Even Triton's internal structure tells the capture story. Despite its frigid surface temperature averaging -235°C - one of the coldest measured surfaces in the solar system - Triton shows signs of significant past geological activity. When it was first captured, the extreme gravitational flexing from its elliptical orbit would have generated enormous internal heat through tidal friction, enough to melt its interior and drive geological processes. This heating would explain the geologically young surface features that Voyager 2 photographed during its 1989 flyby, including what appear to be cryovolcanoes that erupted nitrogen gas and ice.

To grasp why Triton's retrograde orbit is so significant, you need to understand how retrograde motion differs from the norm. In our solar system, nearly everything rotates and orbits in the same direction - counterclockwise when viewed from above the Sun's north pole. This uniform motion is a direct consequence of how the solar system formed from a rotating disk of gas and dust 4.6 billion years ago. The disk's rotation determined the direction everything would spin: the Sun's rotation, the planets' orbits, the planets' rotations, and their moons' orbits.

Retrograde orbits go against this cosmic grain. Among large moons, they're extraordinarily rare because moons typically form from debris disks around their planets - disks that naturally inherit the planet's rotation direction. Small irregular moons with retrograde orbits are more common, but these are all captured asteroids or Kuiper Belt objects, usually just tens of kilometers across. Triton is special because it's both retrograde and enormous.

The mechanics of retrograde orbits have been studied extensively through both observation and theory. Interestingly, some types of retrograde orbits can be more stable than equivalent prograde orbits. This seems counterintuitive, but it happens because retrograde orbits experience different gravitational perturbations from the planet's non-spherical shape and from other moons. However, this stability advantage doesn't apply to Triton's close-in, circular orbit.

Astronomers have even discovered exoplanets with retrograde orbits around their stars, though these use "retrograde" in a different sense - they orbit opposite to their star's rotation rather than traveling backward along their orbital path. Studies of these systems have revealed that violent dynamical histories, involving close encounters between multiple planets, can flip planetary orbits around. The universe, it turns out, is full of objects that ended up spinning or orbiting the "wrong" way due to chaotic gravitational interactions.

Here's where Triton's story takes its darkest turn. That retrograde orbit that makes Triton so interesting is also killing it, and the mechanism is tidal acceleration - or in this case, tidal deceleration.

Tides work both ways. Earth's Moon creates tides in our oceans, but Earth also creates tides in the Moon - bulges in the Moon's shape caused by Earth's gravitational pull. Because Earth rotates faster than the Moon orbits, these bulges are dragged ahead of the line connecting Earth and Moon. The gravitational pull of these bulges acts like a tugboat, gradually pulling the Moon forward in its orbit, adding energy to the orbit and causing the Moon to slowly spiral outward. Earth is losing rotational energy, the Moon is gaining orbital energy, and the result is that the Moon recedes from Earth by about 3.8 centimeters per year.

Retrograde satellites experience tidal forces in reverse. Instead of spiraling outward like our Moon, Triton loses orbital energy and spirals inward toward Neptune - a process that will eventually lead to its complete destruction at the Roche limit.

This process works in reverse for retrograde satellites. Triton orbits Neptune every 5.87 days, but Neptune rotates much faster, spinning once every 16 hours. Neptune's rotation drags the tidal bulges it raises on Triton forward relative to Triton's orbital motion. But because Triton is moving backward relative to Neptune's rotation, "forward" for the bulges means backward along Triton's orbital path. The gravitational pull of these bulges acts as a brake, constantly slowing Triton down, removing energy from its orbit, and causing it to spiral inward.

The rate of this orbital decay depends on complex factors including the tidal forces involved, Triton's internal structure, and how much energy is dissipated as heat through tidal flexing. Current calculations suggest Triton is spiraling inward slowly - very slowly - losing perhaps a few centimeters of altitude per year. At this rate, Triton will continue its inward death spiral for approximately 3.6 billion years.

But eventually, Triton will cross a threshold called the Roche limit. This is the distance at which tidal forces from the planet become stronger than the moon's own gravity holding it together. For a rigid body like Triton, the Roche limit lies somewhere between 2.5 and 3 times Neptune's radius. Once Triton crosses this line, Neptune's gravity will literally tear it apart.

The destruction won't be instantaneous or explosive. Instead, pieces of Triton will begin breaking away, starting with material from its tidal bulges and any structurally weak areas. Over a period that might last thousands to millions of years, Triton will be progressively shredded, its debris spreading around Neptune to form a spectacular ring system potentially far more impressive than Saturn's rings. These rings would be temporary on cosmic timescales - over tens of millions of years, the debris would either fall into Neptune or be ejected from the system.

Triton's fate teaches us several important lessons about planetary science. First, it demonstrates that moon systems aren't static. They evolve, sometimes dramatically, over billions of years. The current tidal acceleration processes we can observe hint at the large-scale changes that occur over deep time.

Second, Triton shows that the outer solar system had a violent past. The early solar system wasn't the orderly, clockwork mechanism we see today. Planets migrated, objects were captured or ejected, and moon systems were destroyed and reformed. Gravitational capture events like Triton's were probably common in the early days, though most captured objects wouldn't have been large enough to survive and become major moons.

"The study of Triton provides invaluable insights into Kuiper Belt composition because it's essentially a captured Kuiper Belt object that's much more accessible than the distant belt itself."

- UC Santa Cruz Planetary Science Research

Third, Triton provides a window into the Kuiper Belt's composition and structure. Because Triton is much closer than the Kuiper Belt and was studied by Voyager 2, it's given scientists valuable information about what Kuiper Belt objects are made of and how they behave. The Kuiper Belt itself is a vast reservoir of icy bodies beyond Neptune, and understanding objects like Triton helps us understand the outer reaches of our planetary system.

Finally, Triton reminds us that worlds have lifespans. Just as stars are born, evolve, and die, so too do moons. Triton's story has a beginning (its formation in the Kuiper Belt), a middle (its current existence as Neptune's captive moon), and an end (its eventual destruction at the Roche limit). In the grand sweep of solar system history, Triton is already in its final chapter.

Future missions could provide unprecedented insights into Triton's story. The proposed Trident mission, though not currently selected for NASA funding, would fly by Triton to map its surface, study its thin nitrogen atmosphere, and analyze the composition of its icy surface in detail. Such a mission could confirm the capture hypothesis by definitively measuring Triton's composition and comparing it to known Kuiper Belt objects.

More immediately, Earth-based telescopes and space telescopes like James Webb are increasingly capable of studying Triton despite its distance from Earth. Spectroscopic observations can reveal the composition of Triton's surface and atmosphere, while precision astrometry can measure its orbital position accurately enough to detect the subtle changes caused by tidal evolution.

The study of Triton also has implications for understanding exomoon systems around distant planets. If gravitational captures are common, then we might expect many exoplanets to have captured moons, some possibly in retrograde orbits. As exomoon detection techniques improve, we may discover that our solar system's one backward moon isn't so unique after all.

By the time Triton finally meets its end 3.6 billion years from now, Earth will be a vastly different world - if it still exists at all. The Sun will be significantly brighter and hotter, well on its way to becoming a red giant. Any humans or human descendants who witness Triton's destruction will be as different from us as we are from the first single-celled organisms that inhabited Earth 3.6 billion years ago.

Yet Triton's fate is already written in the mathematics of orbital mechanics and tidal forces. Every second, its retrograde orbit removes a tiny amount of energy, pulling it imperceptibly closer to Neptune. Every day, every year, every million years, the gap closes. Triton may be the only major moon in the solar system with a retrograde orbit, but it's also a reminder that in the cosmic long game, even worlds have expiration dates. The backward moon is running out of time, spiraling toward an inevitable and spectacular end that humans will almost certainly never witness, except through the predictive power of physics and mathematics.

Neptune may lose its largest moon, but it will gain something magnificent in return: a ring system born from Triton's destruction, a temporary monument to the strange moon that orbited backward for billions of years before gravity finally caught up with it.

Triton, Neptune's largest moon, orbits backward at 4.39 km/s. Captured from the Kuiper Belt, tidal forces now pull it toward destruction in 3.6 billion years.

Banned pesticides like DDT persist in food chains for decades, concentrating in fatty fish and dairy products, then accumulating in human tissues where they disrupt hormones and increase health risks.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

Humans systematically overestimate how single factors affect future happiness while ignoring broader context - a bias called the focusing illusion. This cognitive flaw drives poor decisions about careers, purchases, and relationships, and marketers exploit it ruthlessly. Understanding this bias and adopting systems-based thinking can improve decision-making, though awareness alone doesn't eliminate the effect.

Scientists have discovered lichens living inside Antarctic rocks that survive extreme cold, radiation, and desiccation - conditions remarkably similar to Mars. These cryptoendolithic organisms grow just micrometers per year, can live for thousands of years, and have remained metabolically active in Martian simulations, offering profound insights into life's limits and the potential for extraterrestrial biology.

The nonprofit sector has grown into a $3.7 trillion industry that may perpetuate the very problems it claims to solve by professionalizing poverty management and replacing systemic reform with temporary relief.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.