Spectacular Flares From the Milky Way's Black Hole

TL;DR: Miranda, one of Uranus's smallest moons, hosts 20-kilometer cliffs - the tallest in the solar system - and chevron-shaped coronae formed by ancient tidal heating. These features reveal a violent past: orbital resonances melted Miranda's interior, creating a subsurface ocean that later froze and expanded, tearing the surface apart.

In the outer reaches of our solar system, a tiny moon orbits Uranus with cliffs so extreme they make Earth's Grand Canyon look like a pothole. Miranda, just 470 kilometers across, hosts Verona Rupes - a 20-kilometer-tall cliff that would take you 12 minutes to fall from top to bottom in the moon's weak gravity. You'd land at 200 km/h, having drifted through one of the most spectacular geological features in the known universe.

What's remarkable isn't just the height. It's what these cliffs reveal about Miranda's violent past - a history written in chevron-shaped scars and fractured ice, telling the story of a moon torn apart by tidal forces, melted from within, and frozen solid again.

When Voyager 2 swept past Uranus in 1986, it captured images of Miranda that left planetary scientists baffled. The moon's surface looked like someone had smashed it to pieces and reassembled it wrong - ancient cratered terrain sat next to impossibly young grooved regions, separated by cliffs that defied logic.

The most striking features are three massive coronae - Arden, Elsinore, and Inverness - each stretching over 200 kilometers wide. They're shaped like chevrons or trapezoids, with bright V-shaped ridges at their centers and concentric grooves radiating outward. Nothing else in the solar system looks quite like them.

For decades, scientists proposed wild theories. Maybe Miranda had been completely shattered by a massive impact and gravitationally reassembled itself, its pieces settling back together in random order. It was a dramatic idea, but the physics never quite worked out.

The real answer turns out to be even more extraordinary: Miranda once had a global ocean beneath its icy crust, and when that ocean froze, it literally tore the moon's surface apart.

Miranda's 20-kilometer cliffs couldn't exist on Earth - the rock would crumble under its own weight. But in the moon's 0.8% gravity, ice and rock can support extreme vertical faces for hundreds of millions of years.

Miranda sits 129,000 kilometers from Uranus, close enough that the planet's gravitational pull squeezes the little moon like a stress ball. But here's the thing - that squeezing only generates significant heat under specific conditions.

The key is orbital resonance. When two moons orbit at periods related by simple ratios - like 3:1 or 2:1 - their gravitational tugs on each other amplify dramatically. It's like pushing someone on a swing at just the right moment. Each push adds energy, and over time, those synchronized pushes can generate enormous forces.

Scientists now believe Miranda was once locked in a 3:1 orbital resonance with Umbriel, another of Uranus's moons. This resonance forced Miranda's orbit to become eccentric - stretched into an ellipse rather than a circle. As Miranda moved closer to and farther from Uranus on each orbit, the planet's tidal forces flexed the moon's interior like kneading dough.

That flexing generates heat through friction. And on Miranda, it generated a lot of heat - enough to raise internal temperatures by hundreds of degrees, melting the ice deep below the surface.

Computer models working backward from Miranda's current surface features suggest something remarkable: between 100 and 500 million years ago, Miranda had a subsurface ocean up to 100 kilometers thick beneath an ice shell only 30 kilometers deep.

To put that in perspective, Miranda's entire radius is only 235 kilometers. This wasn't a small puddle - it was an ocean that comprised a substantial fraction of the moon's total volume. The ocean likely existed in the lower portion of what scientists call the "hydrosphere," the layer of water and ice surrounding Miranda's rocky core.

But subsurface oceans don't necessarily create coronae. That requires something more dramatic.

New research suggests the ocean may have actually reached boiling conditions. Under the right circumstances - when tidal heating thins the ice shell enough - the pressure on the ocean water drops. At the triple point of water (around 0°C at very low pressure), liquid water, ice, and water vapor can all coexist. Drop the pressure further, and the ocean boils.

That's not the kind of boiling you see in a kettle. It's a rapid phase transition where dissolved gases escape and the water itself vaporizes, creating enormous pressure that fractures the ice shell from below. Those fractures propagate to the surface, creating the distinctive patterns we now see as coronae.

"To find evidence of an ocean inside a small object like Miranda is incredibly surprising."

- Tom Nordheim, planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

But boiling alone doesn't explain the precise geometry of Miranda's chevron coronae. For that, you need convection.

When Miranda's interior was warmest, the ice mantle wasn't uniformly solid. Warm, buoyant ice rose toward the surface in localized upwellings called diapirs - think of them as slow-motion lava lamps made of ice. As this warmer ice approached the cold surface, it cooled, spread out horizontally, and then sank back down in a continuous cycle.

These convection cells created organized stress patterns. Above each rising plume, the surface ice stretched and cracked in concentric rings, forming extensional faults. The result: those distinctive V-shaped chevrons at the centers of the coronae, with parallel grooves radiating outward.

Recent computer simulations show that convection powered by tidal heating could have generated about 10 gigawatts of power - enough to create the exact pattern of coronae we observe. The simulations even required a 60-degree reorientation of Miranda's spin axis to match the current locations perfectly, suggesting the moon underwent dramatic rotational changes during its thermal heyday.

Eventually, the orbital resonance that powered Miranda's tidal heating broke down. Maybe Umbriel drifted out of sync. Maybe the system reached a more stable configuration. Whatever the cause, the energy source shut off.

Without continuous heating, Miranda's internal ocean began to freeze from the outside in. And here's where things get destructive: ice occupies about 9% more volume than liquid water. As the ocean froze, Miranda literally expanded.

That 9% volume increase doesn't sound like much, but when you're talking about a 100-kilometer-thick ocean shell turning to ice, it translates to massive surface deformation. The brittle ice crust couldn't accommodate the expansion smoothly. It cracked, fractured, and buckled.

Some models suggest Miranda's total volume increased by about 4% during this refreezing event. Four percent expansion of a 470-kilometer-diameter body means the surface had to stretch by tens of kilometers in places. That's how you get 20-kilometer cliffs.

The freezing process also explains the juxtaposition of old and young terrain. Areas where the ice shell was thinnest and most recently active show smooth, young surfaces with few impact craters. Areas that remained cold and geologically dead for longer accumulated more craters and look ancient. Miranda didn't reassemble from fragments - it just underwent wildly different rates of geological activity across its surface.

When Miranda's 100-kilometer ocean froze, the moon expanded by 4% - enough to stretch the surface by tens of kilometers and create the tallest cliffs in the solar system.

On Earth, a 20-kilometer cliff couldn't exist. The rock at the base would crumble under the weight of the material above. The structural stress would exceed the compressive strength of even the hardest stone.

But Miranda's surface gravity is only about 0.8% of Earth's - barely strong enough to notice. An object dropped from the top of Verona Rupes accelerates so slowly that it takes 12 minutes to reach the bottom, landing at roughly 200 km/h. That's fast in human terms but gentle compared to the catastrophic impact velocities you'd reach falling 20 kilometers on Earth.

The low gravity also means the cliff face experiences far less structural stress. The ice and rock can support steeper slopes without collapsing. Combined with the near-vacuum surface conditions - no wind or rain to erode the edges - cliffs on Miranda can maintain extreme vertical faces for hundreds of millions of years.

The question now is whether Verona Rupes extends even further beyond the terminator into Miranda's northern hemisphere, which Voyager 2 never imaged. Some estimates suggest it could be even taller than 20 kilometers in areas we haven't yet seen.

Miranda's story fits into a broader pattern emerging across our solar system: icy moons with subsurface oceans are common, not rare.

Jupiter's moon Europa has a global ocean beneath an ice shell, kept liquid by tidal heating from orbital resonances with Io and Ganymede. Saturn's tiny moon Enceladus actively sprays water vapor into space from geysers at its south pole, powered by a 2:1 resonance with Dione. Even Titan, Saturn's largest moon, likely has a subsurface ocean despite its dense atmosphere and methane lakes at the surface.

What sets Miranda apart is the combination of extreme surface features and its small size. At just 470 kilometers across, Miranda is barely one-seventh the diameter of our Moon. Finding evidence of such dramatic internal activity on a body this small challenges our assumptions about where geological processes can occur.

The coronae on Venus are larger, but Venus is a planet with continuous volcanic activity. The tectonic features on Europa are extensive, but Europa is three times Miranda's diameter with a much thicker ice shell. Miranda achieved its extreme geology in a compact package, driven by temporary tidal heating that has long since faded.

"We find that convection in Miranda's ice shell powered by tidal heating can generate the global distribution of coronae, the concentric orientation of sub-parallel ridges and troughs, and the thermal gradient implied by flexure."

- Noah P. Hammond and Amy C. Barr, Geology journal

We've learned an astonishing amount about Miranda from a single spacecraft flyby nearly 40 years ago. But Voyager 2's images only captured the southern hemisphere during a brief encounter. The northern half of Miranda remains essentially unknown.

NASA and ESA have both proposed missions to the Uranus system, but none are currently funded. The most recent proposals target launch dates in the 2030s, which means we're at least 15 years away from new close-up images even in the best-case scenario.

Several key questions remain unanswered:

Could Miranda's subsurface ocean still exist in some reduced form? If heat production from radioactive decay in the rocky core provides even modest warming, perhaps a thin layer of liquid water persists beneath the refrozen shell. This possibility has huge implications for astrobiology.

Did Miranda undergo multiple heating and freezing cycles? The three coronae might represent different episodes of tidal heating rather than a single event. Each resonance with another moon could have reheated the interior, creating a complex thermal history.

How common are boiling oceans in icy moons? If tidal heating can thin ice shells enough to trigger phase transitions, this process might shape the surfaces of many ocean worlds we haven't yet studied closely.

What caused the orbital resonances to end? Understanding what disrupts these gravitational relationships could help us predict where else in the solar system we might find evidence of past or present tidal heating.

Miranda's story transforms how we think about habitability in the outer solar system. For life as we know it, you need liquid water, organic compounds, and an energy source. Miranda likely had all three during its tidally heated phase.

The moon's bulk density suggests it's about 60% water ice and 40% rocky material. The rocky core would have provided minerals and potentially organic compounds. The tidal heating provided energy - likely far more than sunlight at Uranus's distance of 2.9 billion kilometers from the Sun.

We don't know if Miranda's ocean lasted long enough for life to emerge. The heating episodes might have been too brief or too intermittent. But the fact that such a small body could create and maintain an ocean for millions of years suggests habitable environments might be more common than we thought.

Each newly discovered ocean world expands the real estate where life might exist. Europa, Enceladus, Titan, and now Miranda all tell variations of the same story: tidal heating can create warm, liquid environments in places where sunlight barely matters.

At just 470 kilometers across, Miranda is one-seventh the diameter of our Moon - yet it hosts the solar system's tallest cliffs and shows evidence of a past subsurface ocean that could have harbored the ingredients for life.

Imagine standing on Miranda's surface, perhaps at the rim of Verona Rupes. Above you, Uranus fills nearly 10 degrees of sky - about 20 times the apparent size of our Moon as seen from Earth. The planet's blue-green disc, tilted on its side, rotates with its rings edge-on to your view.

The sun is a bright point of light, too distant to feel as warmth, casting long shadows across the fractured ice plain. The cliff edge drops away into darkness, its base lost in shadow two hours' free-fall below.

This alien landscape - the chevron coronae, the impossible cliffs, the patchwork surface of old and new terrain - all emerged from the elegant mathematics of orbital mechanics and the relentless grinding of tidal forces. What looks like chaos follows strict physical laws, telling a story of heat, pressure, freezing, and expansion written in ice and rock.

Miranda reminds us that even the smallest worlds can harbor profound complexity. Its extreme features, born from temporary gravitational relationships between moons we've barely glimpsed, reveal dynamic processes that might be common throughout the icy satellite systems of giant planets.

We've only seen half of this tiny moon once, decades ago. What other surprises wait in the unexplored hemisphere, in the detailed chemistry of the ice, in the structure of the partially frozen ocean that might still lurk beneath the surface?

The answers are there, frozen in time on a small moon 2.9 billion kilometers away, waiting for the next spacecraft to arrive and look closely.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

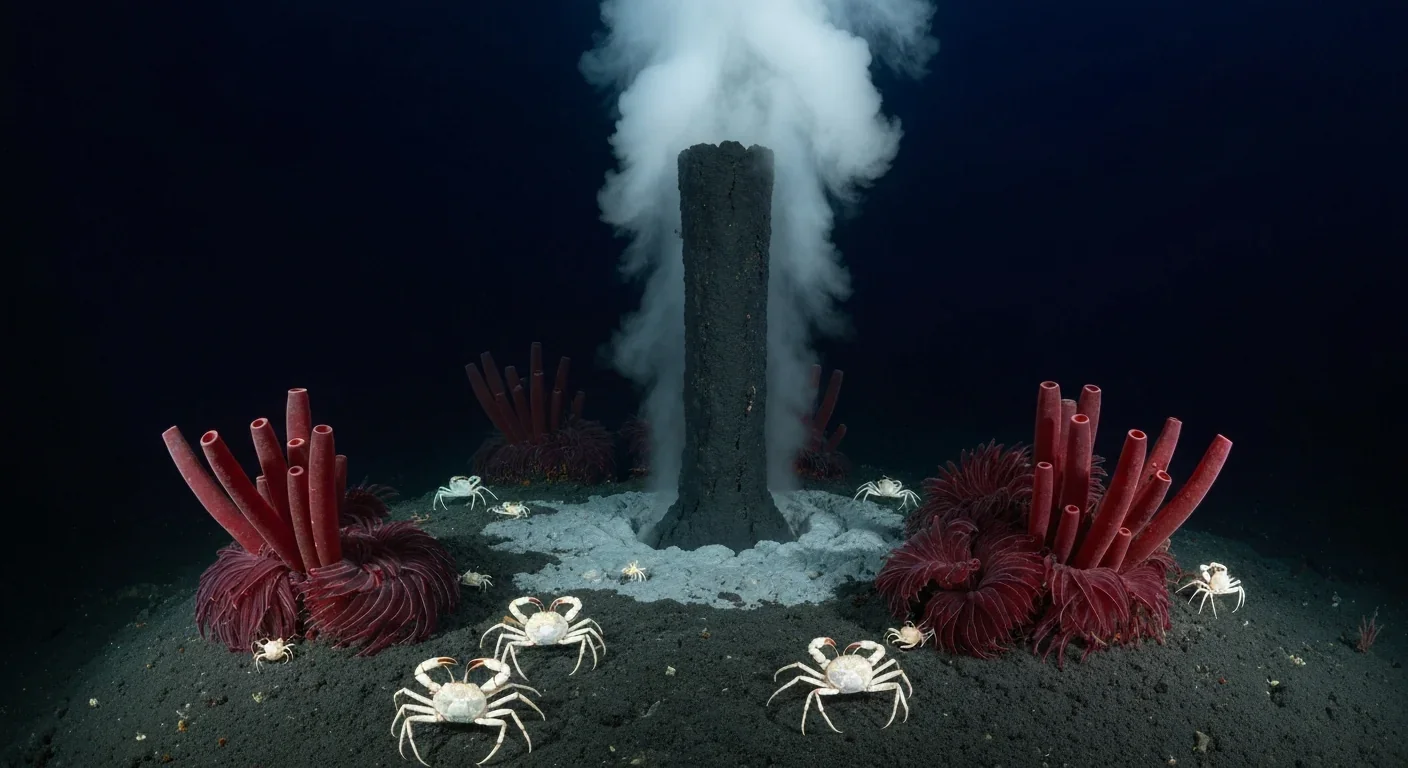

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.