Spectacular Flares From the Milky Way's Black Hole

TL;DR: Magnetar starquakes are the universe's most powerful earthquakes, releasing more energy in milliseconds than the Sun produces in 100,000 years. Recent discoveries show these cosmic events forge heavy elements like gold and platinum, connecting stellar violence to the origins of life itself.

Imagine an earthquake so powerful it releases more energy in a tenth of a second than our Sun will produce in the next 100,000 years. Now imagine that earthquake happening not on a planet, but on the surface of a dead star spinning hundreds of times per second, wrapped in a magnetic field a trillion times stronger than Earth's. This isn't science fiction - it's a starquake on a magnetar, and we're just beginning to understand these cosmic cataclysms that dwarf anything in our terrestrial experience.

On December 27, 2004, something extraordinary happened. Satellites across the solar system suddenly went haywire. Earth's ionosphere - our planet's protective electromagnetic shield - rippled and distorted. For a brief moment, instruments designed to detect the faintest whispers from distant galaxies were completely overwhelmed. The culprit? A starquake on SGR 1806-20, a magnetar located 50,000 light-years away. Despite that staggering distance, the flare was the brightest event ever recorded from beyond our solar system.

Twenty years later, researchers analyzing archival data from that event have discovered something even more remarkable: direct evidence that the flare created heavy elements like gold, platinum, and uranium through a process called r-process nucleosynthesis. These cosmic earthquakes aren't just releasing energy - they're forging the building blocks of planets and, ultimately, life itself.

To understand magnetar starquakes, you need to wrap your mind around just how extreme these objects are. Magnetars are a rare type of neutron star, the collapsed cores of massive stars that exploded as supernovae. After the explosion, what remains is a sphere roughly 20 kilometers across - about the size of Manhattan - but containing 1.4 times the mass of our entire Sun.

The density is almost incomprehensible. A teaspoon of neutron star material would weigh about 10 million tons on Earth. But what makes magnetars special among neutron stars is their magnetic field strength: between 10^14 and 10^15 Gauss, thousands of times stronger than ordinary neutron stars and about a trillion times more powerful than Earth's magnetic field.

A magnetar's magnetic field is roughly 10 billion times stronger than the most powerful magnets humans have ever created. At distances of just 1,000 kilometers, it would literally rip apart the molecular bonds holding atoms together.

To put that in perspective, the most powerful magnets humans have ever created reach about 100,000 Gauss. A magnetar's field is roughly 10 billion times stronger. At distances of just 1,000 kilometers from a magnetar, the magnetic field would be lethal to any biological organism, literally ripping apart the molecular bonds that hold atoms together.

What creates such extreme magnetism? Current theories suggest magnetars form when certain massive stars collapse, and the conservation of magnetic flux from the original star gets compressed into a tiny volume. As the star shrinks from millions of kilometers to just 20, the magnetic field intensity increases by factors of billions. Some researchers also think rapid rotation during the collapse generates additional field strength through dynamo effects.

Only about 30 confirmed magnetars exist in our Milky Way galaxy, out of roughly 8,000 known neutron stars. They're incredibly rare, and they don't stay active forever. Magnetars are thought to be young - typically less than 10,000 years old - and their extreme fields gradually decay over tens of thousands of years until they resemble more typical neutron stars.

The surface of a magnetar isn't just hot and dense - it's structured in ways that challenge our understanding of matter itself. Think of it as having three distinct layers, each with properties more extreme than anything we can recreate in laboratories.

The outermost layer is the crust, extending from the surface down to depths where the density reaches about 100 trillion grams per cubic centimeter. This crust is made primarily of iron nuclei arranged in a crystalline lattice, similar to how atoms arrange themselves in metals on Earth. But the crushing gravity - 100 billion times stronger than Earth's - compresses these nuclei so tightly that the crust becomes 10 billion times stronger than steel.

Below the outer crust lies what physicists playfully call "nuclear pasta" - and yes, that's the actual scientific term. At these depths, atomic nuclei can no longer maintain their spherical shapes. Instead, they get squeezed into strange configurations that resemble spaghetti (long rods), lasagna (flat sheets), or various types of irregular tubes and structures. These exotic phases of matter can store enormous amounts of elastic energy, like a spring wound to its absolute limit.

"Nuclear pasta phases can store enormous elastic energy, providing a natural laboratory for studying matter under extreme compression and magnetic stress."

- Astrophysics Research

Deeper still is the liquid core, where matter exists in a state we've never directly observed: a superfluid of neutrons with superconducting protons mixed in. This inner ocean is magnetically coupled to the solid crust above it, creating a system where changes in one region affect the other.

The problem is that magnetar magnetic fields aren't static. Recent simulations show that the intense magnetic field lines threading through the neutron star evolve over time, shifting and reorganizing themselves. As the field configuration changes inside the star, it exerts tremendous forces on the rigid crust above. The crust tries to resist these forces - remember, it's billions of times stronger than steel - but eventually, something has to give.

A magnetar starquake begins deep within the star, where magnetic field evolution creates shear stresses that build up over months or years. Unlike earthquakes on Earth, which are driven by tectonic plate movements, starquakes are driven entirely by magnetic stress.

Picture the crust as a shell of crystallized iron trying to contain a writhing mass of magnetic field lines. As the field shifts below, the crust deforms elastically at first, bending and flexing like a metal bar under load. But there's a limit to how much strain even super-strong nuclear matter can tolerate. When that limit is exceeded, the crust fractures catastrophically.

The rupture propagates at incredible speed - possibly at a significant fraction of the speed of light - as the stored elastic energy is suddenly released. In that instant, several things happen simultaneously.

First, the fracture releases seismic waves that propagate through the neutron star. These aren't gentle ripples - they're Alfvén waves, oscillations in the magnetized plasma that can carry enormous energy. Recent three-dimensional simulations reveal that non-axisymmetric starquakes launch these waves preferentially in directions perpendicular to the local magnetic field, creating sharply localized emission patterns rather than global spreading.

Second, the crustal fracture violently disrupts the magnetic field structure above the surface. This is where things get really dramatic. The shifting field lines suddenly reconnect and reconfigure, releasing energy at a prodigious rate. During major events, this can produce a burst of 10^46 ergs - that's 1 followed by 46 zeros in energy units.

In 0.1 seconds, a major magnetar flare releases roughly 10^39 joules of energy - more than the Sun produces in 100,000 years. That's the power of a century of sunshine compressed into the blink of an eye.

To give that number context: in 0.1 seconds, a major magnetar flare releases roughly 10^39 joules of energy. The Sun's total power output is about 3.8 × 10^26 watts. Over 100,000 years, the Sun produces approximately 10^38 joules. So yes, a single magnetar flare in a fraction of a second genuinely exceeds a century of solar output.

Third, the quake can actually eject material from the neutron star's surface. This was long considered impossible - the escape velocity from a neutron star is about half the speed of light, and the gravitational binding energy is enormous. But magnetic reconnection events can accelerate particles to relativistic speeds. Analysis of the December 2004 SGR 1806-20 event found evidence for ejected material with masses between 10^-4 and 10^-3 solar masses traveling at about 10% of light speed.

The December 27, 2004 giant flare from SGR 1806-20 remains the gold standard for understanding magnetar outbursts. Located about 50,000 light-years away in the constellation Sagittarius, this magnetar had been relatively quiet before the event. Then, at 21:30:26 UTC, instruments around the solar system registered an unprecedented gamma-ray and X-ray blast.

The initial spike lasted only 0.2 seconds but was so intense that it saturated almost every gamma-ray detector in space. The Swift satellite, NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, and numerous other instruments were temporarily blinded. On Earth, the ionosphere - normally stable at night - suddenly became as ionized as it would be during peak daylight hours. Radio operators reported unusual propagation effects as the ionospheric disturbance altered how radio waves bounced around the planet.

If SGR 1806-20 had been located just 10 light-years away - still far beyond our solar system - the flare would have delivered enough radiation to partially strip Earth's ozone layer. At even closer distances, such events could threaten complex life on planets by increasing surface radiation to dangerous levels.

Following the initial spike, the flare exhibited a declining tail of emission that lasted several minutes, with periodic oscillations likely caused by the magnetar's rotation. But hidden in that tail was something researchers didn't fully appreciate until recently: a delayed component of MeV (mega-electron-volt) gamma rays that peaked about 10 minutes after the initial burst and then decayed over the following hours.

This delayed emission had a specific signature - a quasi-continuous spectrum peaking around 1 MeV, Doppler-broadened by material moving at about 0.1c (10% of light speed). When physicists modeled what could produce such a signal, they found a perfect match: the radioactive decay of freshly synthesized heavy elements created through rapid neutron capture, the r-process.

The r-process is one of nature's ways of building elements heavier than iron. In normal stars, fusion stops at iron because fusing heavier elements consumes energy rather than releasing it. To create gold, platinum, uranium, and other heavy elements, you need an environment with an enormous flux of neutrons that can be captured by atomic nuclei faster than they can radioactively decay.

For decades, scientists thought this only happened in neutron star mergers - the cosmic collisions that produce gravitational waves and bright kilonovae. But the 2004 magnetar flare data tells a different story.

When the starquake ejected neutron-rich crustal material at relativistic speeds, that material underwent explosive decompression. Neutrons that had been packed together at nuclear densities suddenly found themselves expanding into the near-vacuum of space. As they did, they rapidly assembled into heavy atomic nuclei through r-process reactions.

"Magnetar giant flares are viable sites for r-process nucleosynthesis, contributing 1-10% of Galactic heavy-element abundances."

- Patel et al., Astrophysics Research

The result? Approximately 10^-6 solar masses - about the mass of Earth's moon - worth of heavy elements were created in seconds. The decay of these unstable isotopes produced the delayed MeV gamma-ray signature observed in 2004.

This discovery suggests that magnetar flares could contribute 1-10% of the galaxy's heavy element inventory, complementing neutron star mergers as a major source. Given that magnetars are more common than neutron star mergers (which happen perhaps once every 100,000 years per galaxy), their cumulative contribution over cosmic history could be substantial.

It also means that every gold ring, every platinum catalyst, every uranium nucleus on Earth might partly owe its existence to ancient magnetar starquakes that occurred billions of years ago, long before our solar system formed.

Studying magnetar starquakes presents unique challenges. Unlike earthquakes on Earth, where we can place seismometers directly on the surface, we can't exactly install instruments on a neutron star 50,000 light-years away where the surface gravity would instantly crush any spacecraft into a puddle of atoms.

Instead, astronomers rely on indirect detection methods, primarily observing electromagnetic radiation across the spectrum from radio waves to gamma rays. Different parts of the spectrum reveal different aspects of the event.

Radio observations can detect the afterglow as ejected material interacts with the surrounding interstellar medium, providing information about ejecta mass and velocity. X-ray observations reveal the evolution of the magnetosphere as it settles back into a new equilibrium after the quake. Gamma-ray observations capture the initial energy release and, as we now know, the delayed signature of heavy element synthesis.

Recent missions have dramatically improved our detection capabilities. NASA's IXPE (Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer) can measure the polarization of X-rays from magnetar outbursts, revealing the geometry of the magnetic field. The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope continuously monitors the gamma-ray sky, catching transient events that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Ground-based radio telescopes have also played a crucial role. Some magnetar outbursts produce fast radio bursts (FRBs) - millisecond-duration pulses of radio emission that can be detected at cosmological distances. A 2020 event from the galactic magnetar SGR 1935+2154 produced an FRB that was detected both from the magnetar itself and from the ionospheric disturbance it created, providing the first definitive link between magnetars and the mysterious FRB phenomenon.

Theorists complement observations with increasingly sophisticated computer simulations. Three-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic models can now simulate starquake propagation through magnetar crusts, predicting emission patterns that observers can then look for. These simulations run on some of the world's most powerful supercomputers because they need to model matter under conditions where quantum mechanics, general relativity, and plasma physics all matter simultaneously.

Magnetar starquakes serve as natural laboratories for testing physics in regimes we can never recreate on Earth. The conditions inside and around these events push matter and fields to their absolute limits.

Consider the nuclear pasta phases in the magnetar crust. These exotic states of matter can only exist under specific combinations of density and pressure that occur nowhere else in the universe except in neutron star crusts. By observing how starquakes propagate through these layers, we can test theoretical predictions about the behavior of matter at nuclear densities.

Magnetar flares are the universe's most powerful particle accelerators, with electric fields so intense they can accelerate particles to near-light-speed in distances shorter than a human hair - exceeding anything possible with human technology by many orders of magnitude.

The magnetic reconnection events during flares involve electric fields so intense they can accelerate particles to near-light-speed in distances shorter than a human hair. This makes magnetar flares the universe's most powerful particle accelerators, exceeding anything possible with human technology by many orders of magnitude.

Starquakes also provide insights into how crustal failures occur under extreme conditions. Recent research suggests that magnetar crusts likely maintain their solid structure even during major quakes, with fractures propagating through crystallized nuclear matter in ways that have no terrestrial analog. Understanding these exotic fracture mechanics could eventually inform materials science, even if we're centuries away from engineering materials that strong.

There's also a fundamental mystery: magnetar magnetic fields shouldn't exist. According to conventional theory, magnetic fields in neutron stars should decay within about 10,000 years through Ohmic dissipation. Yet we observe magnetars with ages approaching that limit still maintaining their extreme fields. This suggests either unknown mechanisms for field regeneration or fundamental gaps in our understanding of how magnetic fields behave in superconducting superfluids.

Should we worry about magnetar starquakes? The short answer is: only if one happens very close by, which is statistically unlikely but not impossible.

At safe distances - meaning anything beyond about 10 light-years - magnetar flares pose no direct threat to Earth or life. The 2004 event, despite its unprecedented intensity, was 50,000 light-years away and only caused temporary ionospheric disturbances. No harm to humans, no lasting effects.

But imagine if a magnetar existed within a few light-years of Earth and experienced a giant flare. The radiation dose could be severe enough to damage satellites, disrupt telecommunications, and potentially affect Earth's ozone layer. While not an extinction-level event for surface life (the atmosphere and magnetic field provide substantial protection), it could impact aviation, harm orbiting astronauts, and potentially affect atmospheric chemistry for years.

The good news is that we know of no magnetars within 100 light-years of Earth. The closest confirmed magnetar, SGR 0418+5729, is several thousand light-years away. Moreover, magnetars are rare, comprising less than 1% of all neutron stars.

From a space exploration perspective, though, magnetars are definitely hazards to avoid. Any spacecraft or future interstellar mission would need to maintain wide berths around known magnetar locations. The radiation environment near an active magnetar would be immediately lethal to humans and would probably fry most electronics.

Interestingly, some astrobiologists have speculated that magnetar flares could influence galactic habitability. If flares contribute to heavy element enrichment in galaxies, they might indirectly support life by providing the raw materials for rocky planets. But nearby flares could also periodically sterilize regions of galaxies, creating a complex relationship between magnetars and the evolution of life.

The December 2004 event remains unique in its intensity and the wealth of data it provided, but astronomers are eager to observe more magnetar flares to test theories and gather statistics.

About 30 known magnetars are actively monitored, and several show periodic bursting activity. SGR 1935+2154, for example, has produced multiple outbursts since its discovery, including the 2020 event that connected magnetars to fast radio bursts. Each new flare provides additional data points for refining models.

One exciting development is the growing network of multi-messenger astronomy. When a magnetar flare occurs, alerts go out within seconds to observatories around the world and in space, triggering coordinated observations across all wavelengths. This allows astronomers to capture the full evolution of events from the initial burst through the long-term aftermath.

There's also increasing interest in searching for gravitational waves from magnetar starquakes. While the 2004 event predated sensitive gravitational wave detectors, future giant flares might produce detectable space-time ripples if the crustal fracture is sufficiently asymmetric. Advanced LIGO and other gravitational wave observatories are developing search algorithms specifically designed to catch these signals.

The next-generation gamma-ray observatories planned for the 2030s will have dramatically better sensitivity and time resolution, potentially allowing detection of delayed MeV emission from more distant magnetar flares and enabling systematic studies of r-process element production across the galaxy.

Magnetar starquakes remind us that Earth's earthquakes, as destructive as they can be, are cosmically insignificant. The most powerful earthquake ever recorded - the 1960 Chilean quake - released about 2 × 10^18 joules of energy. A major magnetar flare releases roughly 10^39 joules - that's 20 orders of magnitude more energy, or about a hundred billion billion times as much.

These events also connect seemingly disparate phenomena. The gold in our jewelry, the platinum in our car catalytic converters, the uranium powering nuclear reactors - all of these heavy elements were created either in supernova explosions, neutron star mergers, or magnetar flares billions of years ago. We are, quite literally, made of star stuff that went through some of the most violent events the cosmos can produce.

As we continue to study magnetar starquakes, we're not just learning about exotic stars in distant galaxies. We're probing the fundamental nature of matter, testing the limits of our physical theories, and understanding the violent processes that built the universe we inhabit. Every observation brings new surprises - from the discovery of r-process nucleosynthesis to the connection with fast radio bursts - suggesting that these extreme events still have many secrets to reveal.

The universe's most powerful earthquakes happen on dead stars, but their effects ripple across billions of years and light-years, ultimately contributing to the existence of planets, life, and astronomers capable of studying them. That's a humbling thought: the most destructive events in the cosmos are also, in a very real sense, among the most creative.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

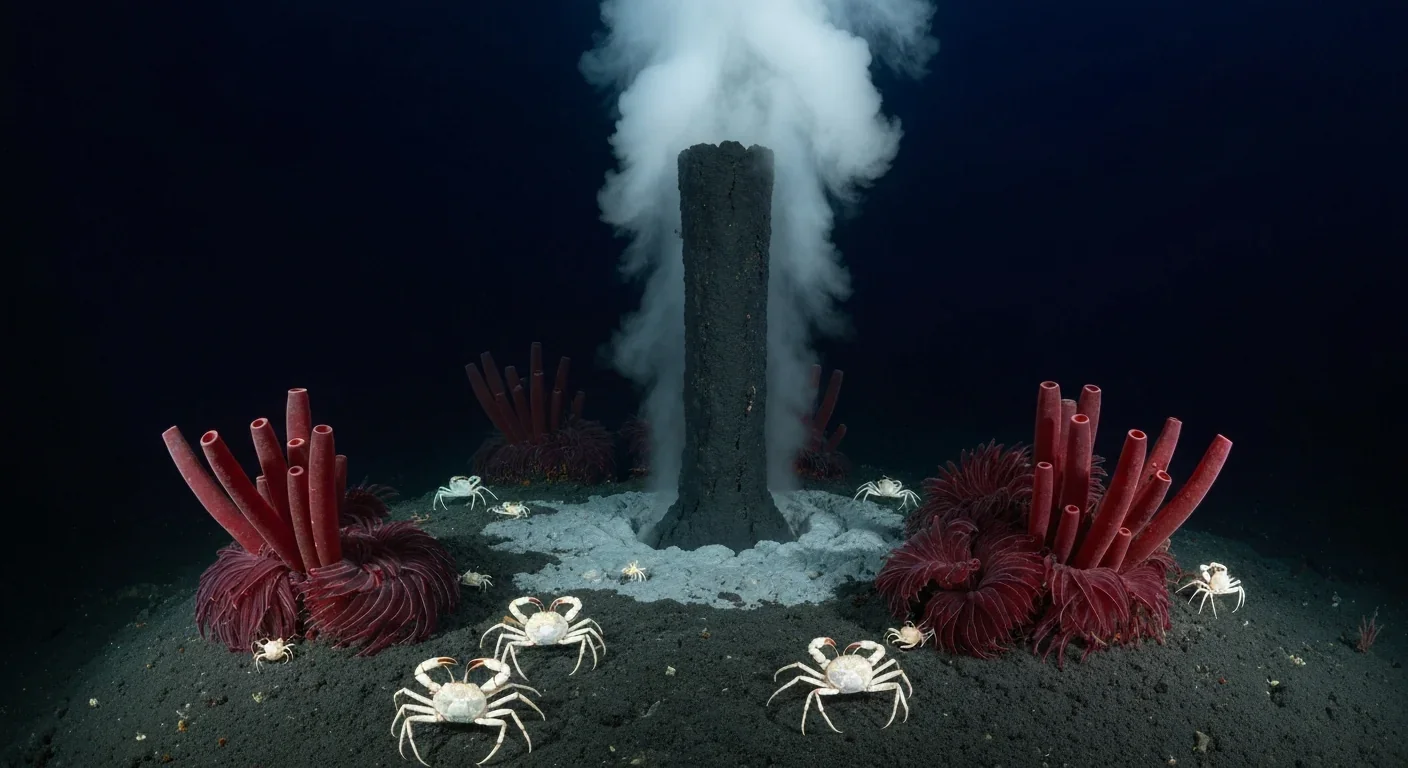

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.