Spectacular Flares From the Milky Way's Black Hole

TL;DR: Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Halfway between Mars and Jupiter, on a dwarf planet dismissed for decades as just another space rock, something unexpected happened. A mountain erupted - but not with lava. With ice.

Ahuna Mons, a 4-kilometer-tall dome on the dwarf planet Ceres, stands as the only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt. When NASA's Dawn spacecraft first spotted it in 2015, planetary scientists couldn't believe what they were seeing. This wasn't supposed to exist. Small, cold bodies like Ceres shouldn't have the internal heat to power geological activity. They should be dead.

Yet there it was: a steep-sided mountain made of salty ice and mud, geologically young, and quite possibly still active. The discovery didn't just rewrite the rulebook on cryovolcanism - it forced scientists to reconsider what we mean by a "dead" world.

Ceres is, by cosmic standards, nobody. At 940 kilometers across, it's the largest object in the asteroid belt, but that's like being the tallest building in a small town. When astronomers discovered it in 1801, they called it a planet. Then they demoted it to asteroid. In 2006, along with Pluto, it got upgraded again to "dwarf planet" - a category that basically means "interesting, but not quite big enough to clear its orbital neighborhood."

For most of its history in our awareness, Ceres seemed geologically boring. Too small to retain much internal heat, too far from the sun to have active surface processes. A frozen relic from the solar system's formation, scientists assumed, with nothing much happening for the past 4 billion years.

Ahuna Mons shattered that assumption. Rising 4 kilometers above Ceres' cratered surface, the mountain spans about 20 kilometers at its base and displays characteristics unlike anything else on the dwarf planet. Its flanks show steep slopes - some approaching 40 degrees - that would be impossible to maintain in rock over geological timescales but make sense for ice that's cold and viscous.

The Dawn mission, which orbited Ceres from 2015 to 2018, mapped the mountain in exquisite detail. High-resolution imaging revealed bright streaks down its flanks, smooth dome-like textures at the summit, and a complete absence of impact craters on its surface. That last detail proved crucial. In the asteroid belt, impacts happen constantly. A crater-free surface means the feature is young - probably less than 240 million years old, possibly as recent as 50 million years.

That might sound ancient by human standards, but it's yesterday afternoon in geological time. Ceres itself is 4.5 billion years old. Something triggered this eruption in the recent past, and researchers believe the internal processes that powered it might still be operating.

Ahuna Mons is probably less than 240 million years old - geologically speaking, that's like discovering something that erupted yesterday on a world that's 4.5 billion years old.

Earth's volcanoes work because our planet's interior is hot enough to melt rock. Magma rises through the crust and erupts as lava, ash, and gases. Simple physics: heat creates buoyancy, pressure finds release, mountains grow.

Cryovolcanism follows similar mechanics but swaps the materials. Instead of molten silicate rock, you get a slurry of water ice, salts, ammonia compounds, and methane. Instead of temperatures around 1,000°C, you're working with something closer to -100°C. The "lava" is still fluid relative to the surrounding crust, but it's ice-cold to us.

On Ceres, the recipe gets more specific. Analysis of Ahuna Mons' composition revealed sodium carbonate (washing soda), ammonium salts, water ice, and clay minerals. This particular cocktail tells a story about what's happening beneath Ceres' surface.

Sodium carbonate doesn't just appear randomly. It forms when liquid water interacts with carbon dioxide and rock over extended periods. Its presence on Ahuna Mons suggests that somewhere below the surface, liquid brine has been reacting with Ceres' rocky core, dissolving minerals, and creating this salty mixture. The ammonium salts act as antifreeze, keeping the brine liquid at temperatures where pure water would freeze solid.

The extrusion process likely worked like squeezing toothpaste from a tube. Pressure from below forced the viscous ice-salt-mud mixture up through fractures in Ceres' crust. Unlike basaltic lava, which flows readily, this cryogenic slurry was thick and sluggish. It oozed out rather than flowing, piling up into a steep dome rather than spreading into flat plains.

Research published in Nature Geoscience suggests that the eruption might have lasted thousands of years, slowly building the mountain layer by layer. As material reached the surface, water ice sublimated into space, leaving behind a concentrated residue of salts and minerals that now armor the dome's exterior.

So where did all that water and salt come from? The answer appears to be a subsurface ocean - or at least large reservoirs of brine scattered throughout Ceres' interior.

Multiple lines of evidence support this. Dawn's gravity measurements detected density anomalies beneath the surface, suggesting pockets of less-dense material consistent with liquid or recently frozen brine. Spectroscopic analysis found hydrated minerals across much of Ceres' surface, indicating that water has been altering the crust for a long time.

The most dramatic evidence comes from Occator Crater, where bright deposits of sodium carbonate shine like beacons against the dark surface. These deposits, the largest known carbonate accumulations beyond Earth, formed when briny water erupted onto the surface and evaporated, leaving behind a thick crust of salts. The fact that some of these deposits appear to be only a few million years old - and possibly forming even today - suggests ongoing geological activity.

"Cryovolcanism provides the heat (energy) and it is a way to bring material that may have biosignatures to the surface of bodies."

- Dr. Rosaly Lopes, Planetary Scientist

Researchers estimate that Ceres' outer layer might contain up to 25% water ice by volume. Deeper down, trapped between an icy crust and a rocky core, could be a global layer of brine or numerous isolated reservoirs. These pockets of liquid remain unfrozen thanks to the antifreeze effect of dissolved salts and, possibly, heat from the decay of radioactive elements in Ceres' interior.

The implications extend beyond geology. Liquid water, organic compounds, and chemical energy - three prerequisites for life as we know it - might all exist in Ceres' subsurface environment. Nobody's suggesting Ceres harbors complex life, but it could potentially support microbial organisms similar to extremophiles found in Earth's deep oceans or Antarctic ice.

Here's the puzzle: if Ceres has subsurface brines and enough internal heat to drive cryovolcanism, why is Ahuna Mons the only obvious cryovolcano on the surface?

The answer involves a process called viscous relaxation. Unlike rock, which maintains its shape over billions of years, water ice is plastic over geological timescales. Given enough time, even solid ice will flow like a very thick fluid, gradually flattening elevated features.

On Ceres, where surface temperatures hover around -100°C and gravitational forces are weak (about 2.8% of Earth's), ice mountains have a half-life of roughly 100-200 million years. That means a cryovolcano that formed a billion years ago would have long since collapsed into a barely noticeable swell on the surface.

Researchers analyzing Dawn's data discovered exactly that: the "ghosts" of perhaps two dozen ancient cryovolcanoes, now reduced to gentle domes and barely perceptible topographic anomalies. These features cluster in Ceres' northern hemisphere, suggesting that region may have been particularly volcanically active in the past.

This discovery transforms our understanding of Ceres' history. Rather than experiencing a single, isolated volcanic event, Ceres appears to have had sporadic cryovolcanic activity throughout its 4.5-billion-year existence. We're simply lucky enough to be observing during a period when one particularly young volcano still stands tall.

The cycle might work like this: internal heat and chemical reactions build up pressure in subsurface brine reservoirs. Eventually, that pressure finds release through a volcanic eruption. The mountain grows rapidly (geologically speaking) over thousands of years, then spends the next hundred million years slowly relaxing and flattening. Meanwhile, pressure builds elsewhere in the interior, and the cycle begins again.

This episodic activity suggests Ceres' interior isn't uniformly cold and static but rather a dynamic system with localized hot spots - places where radioactive decay, chemical reactions, or tidal heating generate enough warmth to keep pockets of liquid water stable for millions of years.

Ahuna Mons isn't the solar system's only ice volcano, just its loneliest. Other worlds display much more dramatic cryovolcanic activity.

Saturn's moon Enceladus shoots enormous geysers of water vapor and organic compounds from fractures near its south pole. The Cassini spacecraft flew through these plumes, directly sampling material from a subsurface ocean and confirming the presence of hydrogen, methane, and complex organic molecules - all ingredients potentially suitable for life.

Jupiter's moon Europa almost certainly has an ocean beneath its icy shell, and recent observations suggest it too might have active cryovolcanic plumes, though less dramatic than Enceladus'. Neptune's moon Triton displays nitrogen geysers and a young surface suggesting active resurfacing. Even distant Pluto shows features that look suspiciously like cryovolcanic domes and flows, though proving current activity is difficult.

What makes Ahuna Mons special isn't just that it exists but where it exists - in the inner solar system, where volatile ices shouldn't have survived for 4.5 billion years.

What makes Ahuna Mons special isn't just that it exists but where it exists. All those other cryovolcanic worlds are either large moons orbiting giant planets (where tidal forces generate internal heating) or distant dwarf planets in the outer solar system (where ices are stable and volatile). Ceres sits in the inner solar system, close enough to the Sun that you'd expect it to have lost most of its volatiles billions of years ago.

Its survival challenges our models of how planetary bodies evolve. Either Ceres formed farther out in the solar system and later migrated inward (one possibility), or small bodies can retain internal heat and volatile materials much longer than we thought (another possibility). Recent research suggests both factors might be in play.

The existence of Ahuna Mons also raises questions about other asteroids. If Ceres can harbor subsurface brines and drive geological activity, might some larger main-belt asteroids do the same? We haven't yet visited them with spacecraft capable of detecting subtle signs of cryovolcanism, but Dawn's discoveries suggest we should look more carefully.

When astrobiologists talk about potentially habitable environments in the solar system, they focus on three requirements: liquid water, organic compounds, and energy sources to drive chemical reactions. Ceres appears to have all three.

Liquid brine reservoirs exist in its interior, potentially stable for millions or billions of years. Spectroscopic observations have detected organic compounds - probably delivered by asteroid impacts but potentially produced by internal chemistry. And energy is available from radioactive decay, chemical reactions between water and rock, and possibly tidal effects.

That doesn't mean Ceres harbors life. The conditions required for life to emerge and persist are still poorly understood, and many astrobiologists believe that even if liquid water and chemistry are present, the energy density might be too low to support biological activity. But it means Ceres deserves a closer look.

The discovery of ongoing or recent geological activity makes this more urgent. On Earth, wherever we find liquid water and chemical energy, we find life. Ceres' subsurface environment might be one of the most accessible potentially habitable environments in the solar system - closer than Europa's ocean, easier to reach than Enceladus' plumes, and potentially still active today.

"The impact that created the Occator crater 20 million years ago likely fractured Ceres' crust, and those fractures today tap into deeper brine reservoirs."

- Dawn Mission Research Team

Future missions could target Ahuna Mons specifically, landing on the dome to sample materials directly erupted from the interior. Such a mission would be technologically challenging but feasible with current capabilities. Unlike drilling through kilometers of ice on Europa, sampling the surface of Ahuna Mons could give us direct access to subsurface materials brought up by cryovolcanic processes.

The diversity of habitable environments in our solar system keeps expanding. We once thought Earth was unique. Then we discovered that icy moons might harbor subsurface oceans. Now we're realizing that even small bodies in the asteroid belt might maintain liquid water and complex chemistry for billions of years. Every discovery widens the range of conditions we should consider when looking for life beyond Earth.

One of the most philosophically intriguing aspects of Ahuna Mons is what it tells us about observation and timing. We live in a specific moment in the solar system's 4.5-billion-year history, and our understanding is shaped by what happens to be visible during this narrow window.

The ghost volcanoes scattered across Ceres' surface remind us that we're seeing only the latest frame in a very long movie. Ahuna Mons will eventually flatten and disappear, becoming just another subtle topographic anomaly that future alien visitors might puzzle over. New cryovolcanoes will probably form elsewhere on Ceres, building up over millennia before succumbing to the same patient gravitational forces.

This perspective changes how we think about planetary activity. We often categorize worlds as "active" or "dead," but that binary is misleading. Ceres is active on timescales of millions of years, with eruptions separated by long periods of apparent quiescence. A civilization that observed Ceres during one of these quiet periods might conclude it was geologically dead and move on, missing the truth entirely.

The same principle applies to our search for life. If microbial organisms exist in Ceres' subsurface brines, they might go through boom-and-bust cycles tied to geological activity. During active periods when fresh nutrients and energy are available, populations could flourish. During quiet periods, they might contract to tiny refuge populations in the most favorable pockets. A mission that arrived during a quiet period might conclude Ceres is sterile, while one arriving during an active phase could find abundant signs of life.

This variability complicates astrobiology but also makes it more interesting. Life in the solar system might not be a simple yes-or-no question but rather a story of ephemeral opportunities, refugia, and periodic expansions and contractions tied to geological and astronomical cycles we're only beginning to understand.

The Dawn mission ended in 2018 when the spacecraft exhausted its fuel supply. It remains in orbit around Ceres, a silent monument to one of NASA's most scientifically productive missions. But the questions it raised remain urgent.

Multiple mission concepts have been proposed to return to Ceres. Some would place a lander on Ahuna Mons itself, drilling into the cryovolcanic dome to sample pristine materials from the interior. Others propose orbiting platforms with more sophisticated instruments to search for ongoing cryovolcanic activity, map subsurface structures in detail, and characterize the composition of any remaining brines.

A sample-return mission, while technically challenging, would bring pieces of Ahuna Mons back to Earth where they could be analyzed with laboratory instruments far more capable than anything we can send into space. Such samples could reveal details about Ceres' chemistry, the age of the eruption, and whether organic compounds or biosignatures are present.

The technological challenges are significant but not insurmountable. Ceres' low gravity (about 2.8% of Earth's) makes landing relatively easy compared to Mars or the Moon. The delta-v required to reach Ceres and return samples is substantial but within the capability of current propulsion systems. The main challenge is cost and priority - convincing funding agencies that Ceres deserves a flagship-class mission when Mars, Europa, and Titan all compete for the same resources.

Yet Ahuna Mons makes a compelling case. It's a unique feature in an accessible location, offering a window into geological processes that might be common throughout the outer solar system. Understanding how small bodies like Ceres retain activity could reshape our models of planetary evolution and expand the range of environments we consider potentially habitable.

When Dawn first imaged Ahuna Mons in 2015, it looked like an anomaly - an isolated feature that didn't fit our understanding of small-body geology. Nearly a decade later, it looks more like a preview of what we'll find as we explore the solar system more thoroughly.

We're discovering that geological activity isn't restricted to large planets with substantial internal heat sources. Even small bodies can maintain pockets of liquid water and drive volcanic activity if the chemistry is right. The line between "active" and "dead" worlds is blurrier than we thought, with activity occurring on timescales that can span millions of years between eruptions.

Most importantly, Ahuna Mons reminds us that the solar system still holds surprises. We've explored less than a tiny fraction of the worlds beyond Earth, and each new discovery seems to expand rather than constrain the diversity of what's possible.

A volcano made of ice on a "dead" dwarf planet in the asteroid belt? Five years ago, most scientists would have said it was unlikely. Today, it's a confirmed fact that's reshaping how we think about planetary science, astrobiology, and the potential for habitability throughout the cosmos.

Somewhere on Ceres, beneath the frozen surface and the crushing silence of space, brine reservoirs might still be active, pressure still building, another eruption possibly millennia or millions of years away. When it comes, it will add another mountain to the collection, one more piece of evidence that even the loneliest worlds can surprise us.

That's the real lesson of Ahuna Mons: never assume you know what a world can do until you look closely. The universe is stranger and more diverse than our theories predict, and the next discovery is always waiting just beyond the edge of what we think we understand.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

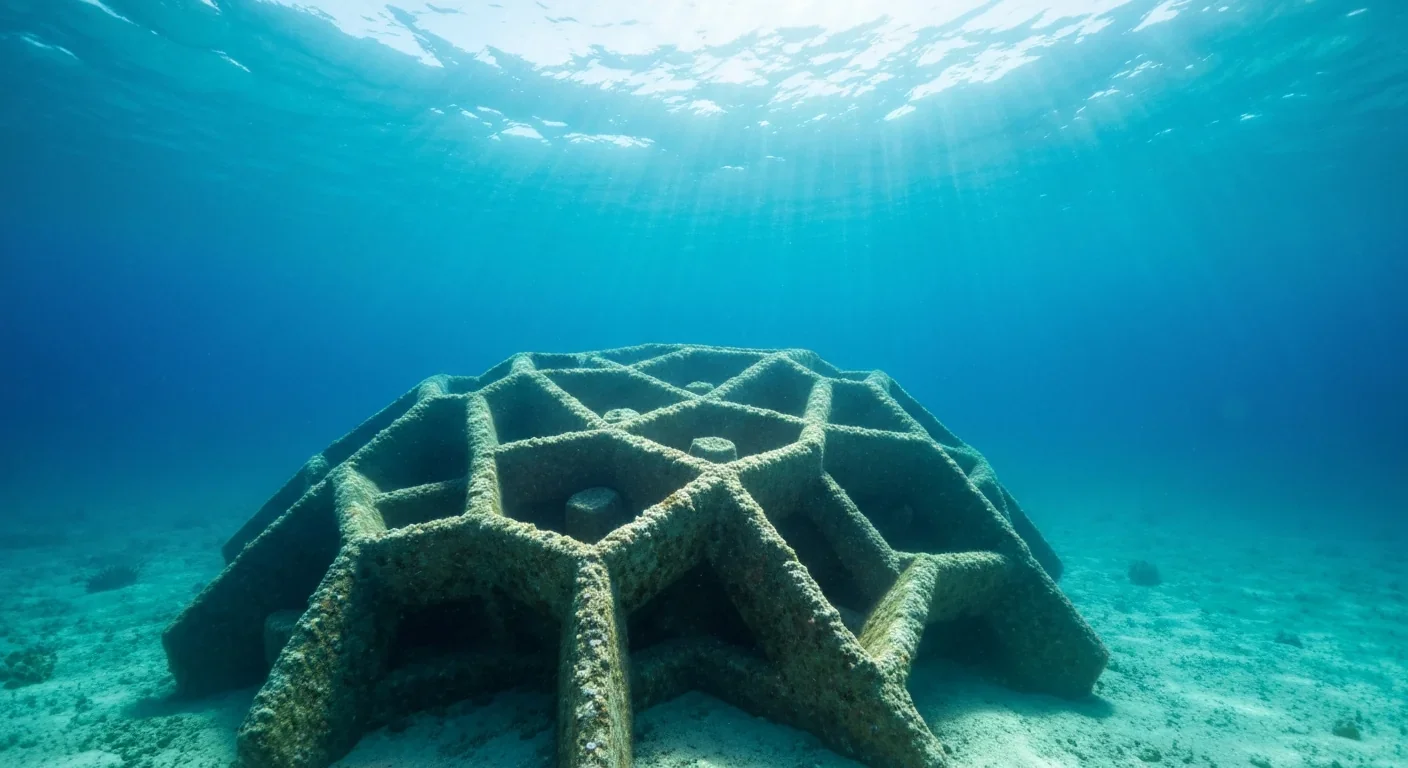

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

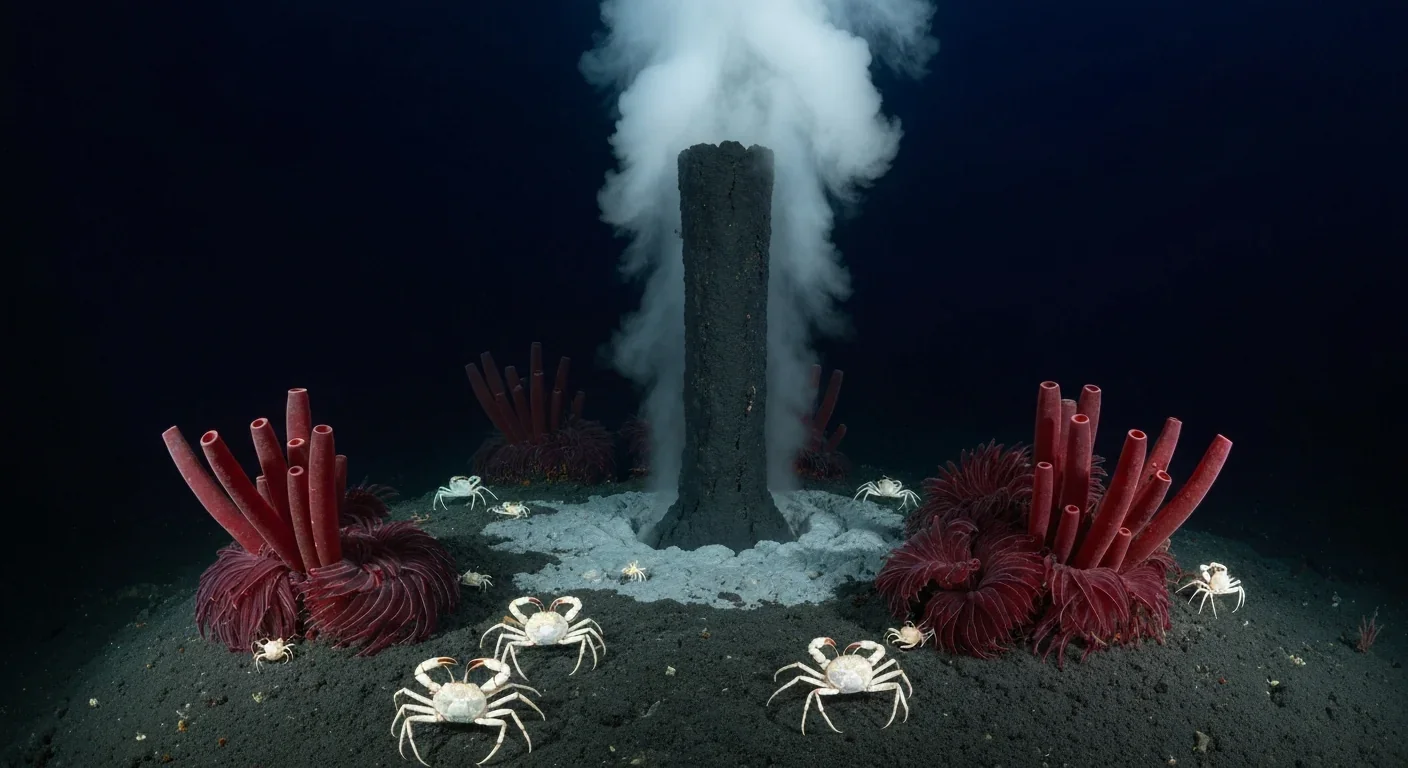

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

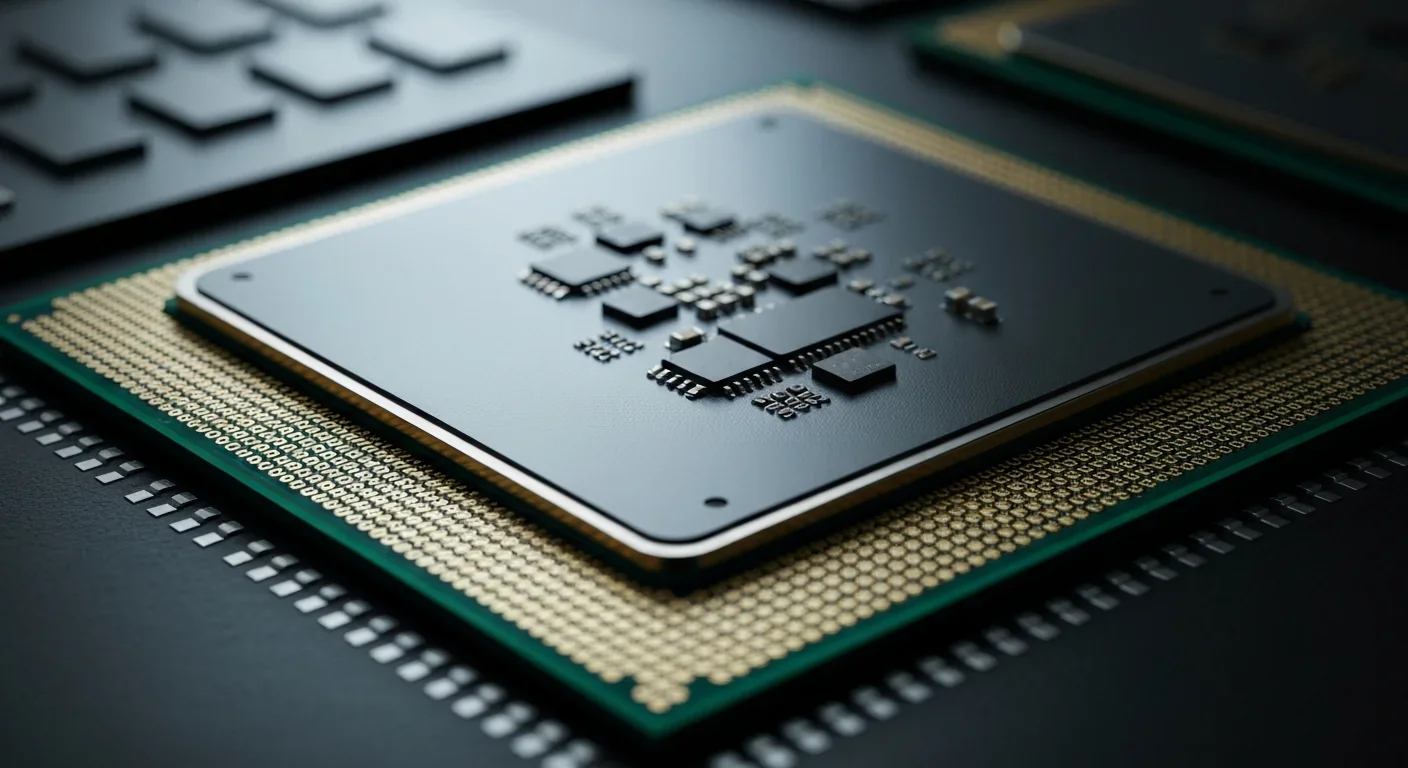

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.