Miranda's 20km Cliffs Reveal Frozen Ocean World

TL;DR: Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Twenty-six thousand light-years away, at the gravitational heart of our Milky Way, sits a cosmic giant that occasionally throws tantrums. Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), the supermassive black hole anchoring our galaxy, periodically erupts in spectacular infrared flares that can brighten by as much as 75 times within minutes. These aren't just pretty light shows - they're windows into some of the most extreme physics in the universe, happening in our own cosmic backyard.

For decades, astronomers have watched Sgr A* with a mix of fascination and frustration. Unlike the blazingly active black holes in distant galaxies that spray jets of matter across millions of light-years, our galactic center is relatively quiet. But "quiet" is relative when you're talking about a black hole with 4 million times the mass of our Sun. Even in its dormant state, Sgr A* exhibits detectable infrared variability nearly every observing night. And when it does decide to flare up, the results are stunning.

On May 13, 2019, astronomers at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii captured something extraordinary. Using adaptive optics to peer through the dusty veil obscuring our galactic center, they watched as Sgr A* underwent its brightest infrared flare ever recorded. The black hole's luminosity shot up by a factor of 75 in just minutes, blazing brilliantly in the near-infrared before fading back to its quiescent state over the course of a couple hours.

The event sent ripples through the astronomical community. After two decades of systematic monitoring, scientists thought they understood Sgr A*'s moods. This flare shattered that complacency. "We've never seen anything like this in the 20 years we've been studying the black hole," said UCLA astronomer Andrea Ghez, whose team has been tracking stars orbiting Sgr A* since the early 2000s.

What makes these flares so scientifically valuable isn't just their brightness - it's what they reveal about the immediate environment around a supermassive black hole. The emission comes from a region smaller than our Solar System, orbiting at roughly 30% the speed of light, just outside the innermost stable circular orbit. That's close enough to feel the full force of Einstein's general relativity, where space-time itself is warped beyond recognition.

The flaring region orbits at 30% the speed of light in a space smaller than our Solar System - an environment where Einstein's relativity governs every photon and particle.

So what exactly triggers these violent outbursts? The leading explanation involves a process called magnetic reconnection - the same mechanism that powers solar flares on our Sun, but cranked up to unimaginable extremes.

Around Sgr A*, matter doesn't fall straight in. Instead, it forms a swirling accretion disk of superheated plasma, threaded through with powerful magnetic fields. As this plasma orbits, the magnetic field lines get twisted, stretched, and tangled. Eventually, they snap and reconnect in explosive bursts that release enormous amounts of energy in seconds.

Recent simulations from a team of astrophysicists using three-dimensional general relativistic magnetohydrodynamic (GRMHD) models have shown how this works in detail. When magnetic field lines with opposite polarities meet in what's called a polarity inversion event, they trigger cascading chains of magnetic reconnection. Electrons caught in these reconnection sites get accelerated to incredible energies - reaching Lorentz factors of several hundred, which means they're moving at 99.9% the speed of light.

These ultra-energetic electrons then spiral through the magnetic fields, radiating synchrotron light predominantly in the near-infrared wavelengths that telescopes on Earth can detect. The process is astoundingly efficient at converting magnetic energy into radiation, though still radiatively inefficient overall - most of the energy gets swallowed by the black hole before it can escape.

There's another compelling model for what we're seeing: orbiting hot spots. Instead of a diffuse cloud of reconnecting plasma, this picture envisions compact blobs of super-hot material - essentially magnetic flux ropes or plasmoids - that get ejected from the inner accretion flow and then orbit the black hole several times before either falling in or being flung outward.

The GRAVITY instrument at the Very Large Telescope in Chile has provided stunning evidence for this scenario. Using interferometry to achieve angular resolution finer than the black hole's apparent size, GRAVITY has tracked these hot spots as they orbit. The observations reveal matter moving at about 30% the speed of light, completing orbits in roughly 45 minutes - exactly what you'd expect for material orbiting just outside the event horizon of a black hole with Sgr A*'s mass.

What's elegant about the hot spot model is how it naturally explains the rapid variability. As the blob orbits, relativistic beaming effects amplify the radiation when the hot spot is moving toward us and diminish it when moving away. Add in the fact that these spots can brighten and fade as they're heated by ongoing reconnection and then cool through radiation, and you get the complex, flickering light curves that astronomers observe.

"We've never seen anything like this in the 20 years we've been studying the black hole."

- Andrea Ghez, UCLA astronomer

Recent work suggests these two models - reconnection and hot spots - aren't mutually exclusive. Reconnection creates the hot spots in the first place. A 2024 study using simultaneous observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, NuSTAR, and the Very Large Array proposed a unified picture: magnetic reconnection launches a flux rope (the hot spot), which then orbits while radiating. The reconnection also accelerates electrons in two directions - some move with the ejected flux rope, producing the infrared flare, while others flow back into the accretion disk, scattering infrared photons up to X-ray energies.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Sgr A* flares is how they light up across the electromagnetic spectrum - but not all at once. The sequence matters, and it tells us about the physical processes at work.

Typically, the near-infrared flare comes first, peaking within about 15-20 minutes. This is the direct synchrotron radiation from the ultra-relativistic electrons. If conditions are right, there's an accompanying X-ray flare that peaks at roughly the same time, caused by inverse Compton scattering - the infrared photons get up-scattered to X-ray energies by the thermal electrons in the surrounding accretion flow.

Then comes the radio afterglow. This lags behind the infrared and X-ray peaks by anywhere from minutes to hours, depending on the observing frequency. Lower frequencies lag more. Why? The ejected flux rope that produced the infrared flare expands adiabatically as it moves outward, cooling as it goes. The expanding cloud becomes optically thick at radio wavelengths due to synchrotron self-absorption - essentially, the cloud is so dense with energetic electrons that it absorbs its own radio emission. As it expands and becomes more transparent, the radio emission gradually emerges, starting at higher frequencies and working down to lower ones.

This multi-wavelength choreography was beautifully captured in April 2024, when for the first time astronomers coordinated observations across JWST's infrared eyes, NuSTAR's X-ray sensitivity, and the VLA's radio dishes. They caught a complete flare sequence: the simultaneous infrared and X-ray spike, followed by the delayed radio enhancement. It's the kind of dataset that can anchor theoretical models for decades.

Coordinated observations across infrared, X-ray, and radio wavelengths revealed for the first time the complete choreography of a Sgr A* flare from start to finish.

In 2011, astronomers discovered something alarming: a giant gas cloud, dubbed G2, was on a collision course with Sgr A*. Predictions suggested it would make its closest approach around 2014, potentially dumping enormous amounts of material onto the black hole and triggering dramatic flaring activity.

The scientific community held its collective breath. Some models predicted fireworks - a feeding frenzy that would light up Sgr A* like never before. Others were more cautious, noting that tidal forces would shred the cloud long before it reached the black hole, diffusing the impact.

As it turned out, the skeptics were right. G2's 2014 pericenter passage was a complete non-event. There was no dramatic increase in flaring activity, no sudden brightening, nothing. The cloud was either tidally disrupted into a diffuse stream that couldn't efficiently fuel the black hole, or - as more recent evidence suggests - it wasn't a pure gas cloud at all, but rather the dusty envelope around a young star. Either way, the episode taught astronomers a valuable lesson: feeding a supermassive black hole is surprisingly finicky.

The G2 non-event also reinforced the idea that Sgr A*'s flares aren't primarily triggered by external material falling in. Instead, they're likely driven by instabilities and reconnection events within the existing accretion flow - the turbulent, magnetized plasma that's already swirling around the black hole from previous infall episodes.

While G2 didn't deliver the expected show, there's growing evidence that Sgr A* does occasionally snack on something more substantial. A recent theoretical study suggests that grazing encounters with brown dwarfs - objects too massive to be planets but too small to be stars - might be responsible for some of the observed flares.

The scenario goes like this: A brown dwarf on an eccentric orbit ventures too close to Sgr A*. The immense tidal forces don't destroy the object completely, but they do strip off a portion of its outer layers - maybe 10^-4 solar masses worth of material. This stripped matter forms two tidal tails that fall back toward the black hole over the course of tens of minutes, getting heated by compression and magnetic reconnection as they descend.

The beauty of this model is that it naturally reproduces the timescale of the flares. The fallback time matches the observed ~40-60 minute duration of major infrared events. The mass scale is right to power the luminosity. And in the dense stellar environment of the galactic center, such encounters should be common enough - perhaps once every few weeks to months - to explain the observed flare frequency.

There's a bonus, too: These tidal encounters don't always destroy the brown dwarf. Some survive as stripped-down objects in tight orbits around Sgr A*, slowly inspiraling over thousands to millions of years. These objects would be powerful sources of gravitational waves - exactly the kind of signal that the future LISA space mission is designed to detect. So electromagnetic flares today might be pointing us toward gravitational wave sources of tomorrow, a beautiful example of multi-messenger astronomy.

In May 2022, the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration released the first image of Sagittarius A*. It was a stunning achievement - using a planet-sized array of radio telescopes to resolve the shadow of our galaxy's central black hole, surrounded by a ring of glowing emission from the accretion flow.

But imaging Sgr A* is vastly harder than imaging M87*, the supermassive black hole that the EHT photographed three years earlier. M87* is much bigger and much more stable; its accretion flow changes on timescales of weeks. Sgr A*, by contrast, is comparatively tiny and changes by the minute. During the observations, matter is swirling around the event horizon, creating a constantly shifting pattern.

This variability is both a curse and a blessing. It makes imaging difficult - the EHT team had to average thousands of snapshots to produce the final picture. But it also means that with sufficiently high time resolution, the EHT could potentially watch flares happen in real-time, tracking hot spots as they orbit the black hole. Future observations, combining EHT's imaging with simultaneous infrared and X-ray monitoring, will provide unprecedented insight into the physics of black hole accretion.

In the cosmic hierarchy of supermassive black holes, Sgr A* is decidedly on the quiet end of the spectrum. Active galactic nuclei (AGN) - black holes that are actively devouring enormous amounts of matter - can outshine entire galaxies, with luminosities millions of times greater than Sgr A* at its brightest.

The difference comes down to fuel supply. AGN are surrounded by abundant gas and dust, often fed by galaxy mergers or large-scale gas inflows. Their accretion disks are thick, dense, and incredibly efficient at converting gravitational energy into radiation. Some launch relativistic jets that extend for millions of light-years.

Sgr A*, by contrast, is essentially starving. It's accreting matter at a tiny fraction of the Eddington limit - the maximum rate at which a black hole can accrete matter before radiation pressure halts further infall. Most of the energy in Sgr A*'s accretion flow gets advected across the event horizon without radiating, a configuration astrophysicists call a radiatively inefficient accretion flow (RIAF).

"The observed X-ray flare is best explained by inverse Compton scattering of near-infrared flare radiation by thermal electrons in the accretion flow."

- 2024 JWST/NuSTAR/VLA study team

This makes Sgr A* an excellent laboratory for studying low-luminosity accretion. Many - perhaps most - supermassive black holes in the present-day universe are in this quiescent state. Understanding how they tick when they're not gorging on gas clouds is crucial for understanding the long-term life cycle of galaxies.

The flares, then, represent brief moments when Sgr A* acts a little more like its hyperactive cousins - when localized instabilities briefly boost the efficiency of energy release. They're glimpses of what this black hole might look like if it had a steady diet instead of occasional snacks.

The next decade promises to revolutionize our understanding of Sgr A* flares. Several upcoming and recently upgraded observatories are poised to contribute:

JWST's mid-infrared capabilities have already proven transformative. In 2024, JWST's MIRI instrument captured its first flare from Sgr A* in wavelengths that were previously difficult to access from ground-based observatories. Extending flare observations into the mid-infrared constrains the temperature and spatial extent of the emitting region, crucial for distinguishing between competing models.

The upgraded Event Horizon Telescope is adding more stations and extending to shorter wavelengths, which will improve both angular resolution and time resolution. The goal is to create "movies" of the accretion flow, capturing the dynamics of flares as they unfold.

GRAVITY+, an enhanced version of the GRAVITY instrument, will achieve even finer astrometric precision, potentially tracking the orbital motion of hot spots down to individual orbits with unprecedented clarity.

Next-generation X-ray missions like XRISM and the proposed Athena observatory will provide high-resolution spectroscopy of X-ray flares, revealing the velocity structure and ionization state of the flaring plasma.

Coordinated multi-wavelength campaigns will be the key. By simultaneously observing across radio, infrared, and X-rays, astronomers can map the complete energy distribution of the flaring electrons and track how energy cascades from magnetic reconnection through particle acceleration to radiation and finally cooling.

Future observatories will create "movies" of Sgr A* flares, watching hot spots orbit the black hole in real-time as magnetic reconnection drives the most extreme particle acceleration in our galaxy.

Beyond their intrinsic drama, Sgr A* flares are valuable probes of fundamental physics in extreme environments. They offer tests of general relativity in the strong-field regime, where Newtonian gravity is hopelessly inadequate. The rapid orbital motion of hot spots, the gravitational redshift of emitted photons, and the bending of light rays around the event horizon all leave signatures in the flare light curves and spectra.

Flares also teach us about magnetic reconnection in relativistic plasmas - a process that's crucial not just around black holes, but also in neutron star magnetospheres, pulsar wind nebulae, and even laboratory fusion experiments. Sgr A* serves as a natural laboratory where reconnection operates under conditions we can't replicate on Earth.

And there's a practical angle: understanding how and when Sgr A* flares helps us interpret observations of distant galaxies in the early universe, where similar low-luminosity black holes dominated the cosmic landscape. By studying the nearest supermassive black hole in exquisite detail, we learn how to read the signals from billions of years ago.

Should we worry about these flares? In a word: no. Despite the dramatic brightening, Sgr A* is far too distant to pose any threat to Earth. The infrared and X-ray radiation from even the brightest flares is utterly negligible by the time it crosses 26,000 light-years to reach us. Our Sun's ordinary output dwarfs any contribution from the galactic center.

But the flares do remind us that we live in a dynamic galaxy. The Milky Way isn't a static collection of stars frozen in space - it's a living, evolving system with a massive black hole at its heart, surrounded by a dense stellar cluster where stars occasionally get torn apart and brown dwarfs have their outer layers stripped away in close encounters.

In a billion years, when the Milky Way collides with the Andromeda galaxy, Sgr A* will likely get a fresh supply of fuel. The encounter will funnel gas toward the galactic centers, and our currently quiescent black hole may become a full-fledged active galactic nucleus, blazing with the luminosity of billions of suns. At that point, flares won't be rare curiosities captured by specialized instruments - they'll be part of a sustained feeding frenzy visible across the universe.

Until then, we have the privilege of watching a supermassive black hole in its quiet phase, with occasional outbursts that offer fleeting glimpses of the physics governing these cosmic monsters. Every flare is an opportunity - a chance to peer into the maelstrom of twisted magnetic fields, ultra-relativistic particles, and warped space-time that exists at the edge of the event horizon.

The giant at the heart of our galaxy is mostly sleeping. But when it stirs, even briefly, it reminds us that we're living in one of the universe's most extreme laboratories - one that's slowly, inexorably, revealing its secrets.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

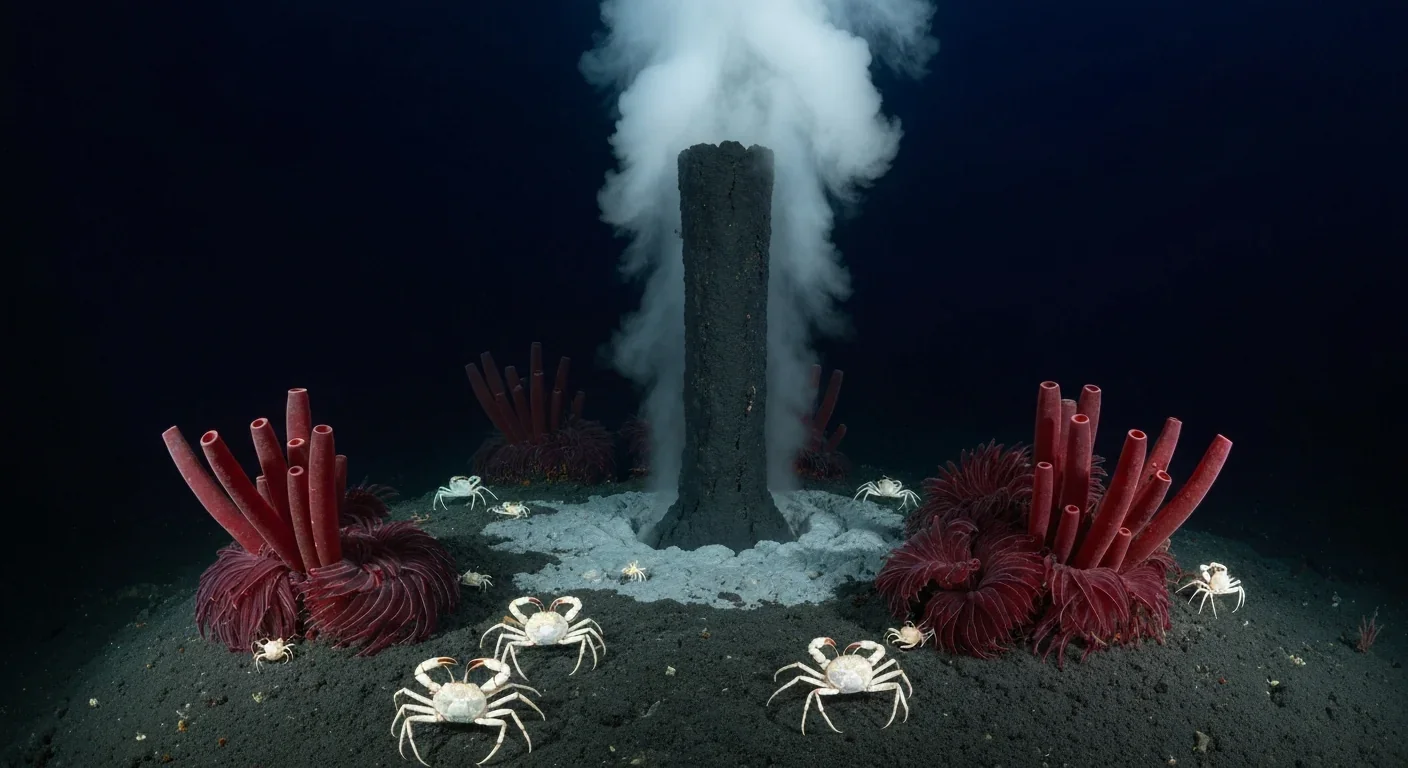

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.