Spectacular Flares From the Milky Way's Black Hole

TL;DR: Three spacecraft will park at L2 in 2029, waiting to ambush the first pristine comet discovered from the Oort Cloud - a frozen time capsule that could reveal how our solar system formed and whether interstellar chemistry seeded Earth with the ingredients for life.

In 2029, three spacecraft will settle into a quiet orbit 1.5 million kilometers from Earth and simply wait. They won't know where they're going. Their target hasn't been discovered yet. It may not exist for years. When it finally appears - a frozen relic hurtling in from the outer darkness for the first time in 4.6 billion years - these patient hunters will have just weeks to wake up, break formation, and intercept a comet traveling faster than a bullet.

This is Comet Interceptor, and it represents something space agencies have never attempted: a mission designed around a target we haven't found yet. While every previous spacecraft launched with a destination already plotted, Comet Interceptor will park itself at the Sun-Earth L2 Lagrange point and wait for telescopes on Earth to spot something worth chasing. It's part sentinel, part ambush predator, and it could fundamentally change how we explore the solar system.

The prize? A pristine comet making its first journey through the inner solar system - an object so ancient and unaltered that it preserves the chemical fingerprints of our cosmic birth.

Not all comets are created equal. The ones we've studied so far, like 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko visited by ESA's Rosetta mission from 2014 to 2016, are what astronomers call short-period comets. They orbit the Sun every few years, and every pass strips away layers of ice and alters their composition. They're like books left out in the rain - still interesting, but smudged and water-damaged.

Dynamically new comets are different. These objects originate in the Oort Cloud, a vast reservoir of icy planetesimals spanning 2,000 to 200,000 astronomical units from the Sun - so far out that the Sun is just another bright star. Out there, temperatures hover barely above absolute zero, and nothing has changed in billions of years. A comet from this region entering the inner solar system for the first time carries pristine material from the solar system's formation, uncooked by solar heat, chemically frozen in time.

Here's where it gets fascinating: recent research suggests that roughly 90% of Oort Cloud objects may have been captured from other stars while the Sun was still in its birth cluster. That means a pristine comet could contain not just primordial solar system material, but interstellar chemistry from neighboring stellar nurseries - a cosmic time capsule holding clues to multiple star systems' early histories.

A pristine Oort Cloud comet could contain material from other star systems, offering a window into interstellar chemistry from billions of years ago.

Studying such an object could answer fundamental questions: Where did Earth's water come from? How did organic molecules necessary for life form and spread through the early solar system? What was the chemical composition of the protoplanetary disk that birthed the planets? Short-period comets have been too altered to answer these questions definitively. A pristine comet hasn't.

Comet Interceptor isn't a single spacecraft but a coordinated trio. The mission comprises Spacecraft A (the ESA mothership), Spacecraft B1 (built by Japan's JAXA), and Spacecraft B2 (built by ESA). This multi-probe architecture serves a crucial purpose: three-dimensional reconnaissance.

When the target appears, the mothership will separate from its two smaller companions. Each will fly through the comet's coma - the cloud of gas and dust surrounding the nucleus - at different distances and angles. While Spacecraft A makes the closest approach to image the nucleus and measure surface properties, B1 and B2 will sample the coma from different vantage points, measuring dust composition, gas density, plasma interactions with the solar wind, and magnetic field characteristics.

This multi-point strategy addresses a major limitation of previous single-spacecraft comet missions. When you send one probe through a dynamic, turbulent environment like a comet's coma, you get a single cross-section - a line through a three-dimensional phenomenon. Three spacecraft can triangulate, measuring how dust density, gas composition, and plasma behavior vary across the coma. It's the difference between sticking a thermometer out the window once versus having a whole weather station network.

The UK is contributing £16 million in national funding to support instruments including MIRMIS (an infrared spectrometer built at Oxford) and a Fluxgate Magnetometer from Imperial College London. These tools will map the comet's thermal characteristics, identify mineral and ice compositions, and measure how the solar wind interacts with cometary material - data that can only be gathered during a close flyby, not from Earth-based telescopes.

The mission's staging area is no accident. L2, located approximately 1.5 million kilometers from Earth on the side opposite the Sun, is a gravitational sweet spot where the combined pull of Earth and the Sun creates a stable orbit. Spacecraft at L2 require minimal fuel to maintain position, conserving propellant for the eventual intercept. It's already home to major observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope and will soon host ESA's Ariel exoplanet telescope - which will carry Comet Interceptor as a co-passenger when it launches in 2029.

But L2 offers more than just stability. It provides an optimal launch point for reaching comets entering the inner solar system. Mission planners have calculated a delta-v budget - the total change in velocity the spacecraft can achieve with its onboard fuel - of about 1.5 kilometers per second. That limits which comets can be targeted: the ideal candidate must pass between 0.9 and 1.2 astronomical units from the Sun, cross the ecliptic plane at an accessible angle, and approach at a trajectory that allows the spacecraft's solar panels to maintain adequate power (angles between 45° and 135° to the Sun).

"The flyby of the comet can't take place at more than 70 km/s to avoid dust damage to the probes."

- Universe Today, reporting on Comet Interceptor mission constraints

The flyby speed must also stay below 70 kilometers per second - about 252,000 kilometers per hour - to prevent the small probes from being destroyed by high-velocity dust impacts. At 70 km/s, even microscopic particles hit with explosive force. So the mission team is hunting a Goldilocks comet: active enough to be scientifically interesting, but not so violently outgassing that it endangers the probes.

This is where the Vera C. Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) becomes critical. Starting operations this decade, LSST will scan the entire visible sky every few nights, discovering comets months or even years before they reach peak brightness. Historical data shows that from 1898 to 2023, astronomers cataloged 132 dynamically new comets - but most were faint and discovered only shortly before perihelion, giving mission planners no time to react.

LSST changes that calculus. Its deep, wide-field imaging will catch comets earlier, while they're still far from the Sun. Mission scientists led by Professor Colin Snodgrass at the University of Edinburgh have modeled the probability of finding suitable targets. Their pre-print study on arXiv analyzes past comet discoveries and projects future detection rates, concluding that while the odds are reasonable, the mission will likely need to accept a "good enough" target rather than an ideal one.

The target selection process involves a delicate balance. Too faint, and the scientific return diminishes. Too active, and the spacecraft risk damage. The team has identified past comets like C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) as examples that would have fit the mission's constraints - bright enough for detailed study, but not so violently outgassing as to threaten the probes. The real trick is having enough warning time between discovery and optimal intercept.

Once a suitable candidate emerges, the clock starts ticking. Ground controllers will command the trio to depart L2, navigate to the intercept trajectory, separate into formation, and execute the flyby - all coordinated autonomously because the encounter happens at such high speed that real-time control from Earth is impossible. The spacecraft must operate independently, identifying the nucleus amid the glowing coma, adjusting their flight paths on the fly, and capturing data during what amounts to a cosmic blink.

From 1898 to 2023, only 132 dynamically new comets were discovered - and most gave mission planners no time to react. LSST aims to change that.

Designing a spacecraft to wait for years and then spring into action presents unique challenges. Most space probes are built for continuous operation or hibernation with periodic wake-ups. Comet Interceptor must do both: remain viable during an indefinite parking period while staying ready to execute a rapid, complex maneuver with minimal preparation time.

Thermal cycling is a major concern. At L2, the spacecraft experience constant solar exposure, cycling through temperature extremes as they rotate. Electronics must survive years of this without degradation. Fuel systems must remain functional. Batteries and power systems must maintain capacity. It's like keeping a car in the garage for an unknown number of years, then expecting it to accelerate instantly to top speed.

Communication presents another hurdle. During the wait at L2, the spacecraft will maintain contact with ground stations, receiving software updates and health checks. But once the intercept begins, the rapid flyby requires autonomous navigation and communication relay through the mothership. The two smaller probes must transmit their data to Spacecraft A, which acts as a relay to Earth, all while moving at tens of kilometers per second through an environment filled with gas, dust, and plasma.

The mission was designated as an ESA F-class (fast) mission - designed for rapid development and a budget significantly lower than medium or large-class missions. That constraint drives clever design choices: leverage existing technology where possible, accept calculated risks, and focus on essential science instruments rather than comprehensive suites.

When the three spacecraft slice through their target's coma, they'll gather data impossible to obtain any other way. Instruments will analyze gas composition, identifying volatile ices and organic molecules. Dust collectors will sample particles, measuring grain sizes and mineral content. Cameras will image the nucleus at resolutions revealing surface textures, craters, jets, and layering.

The Fluxgate Magnetometer will map magnetic fields in the coma, showing how solar wind plasma interacts with the comet's outgassing. This interaction creates a bow shock and plasma tail - phenomena glimpsed during previous missions but never measured simultaneously from multiple points. Understanding these plasma dynamics helps decipher how solar wind strips atmospheres from planets and comets alike, a process critical to planetary habitability.

Comparing this pristine comet's composition to the evolved comets studied by Rosetta, Stardust, Deep Impact, and Giotto will reveal what changes when comets age. Do repeated solar passes cook away certain ices first? How quickly do organic molecules break down under UV radiation? Does the dust-to-gas ratio shift as surface layers erode?

The mission could also shed light on the origins of Earth's water and organics. Previous comet missions found complex organic molecules and water ice - ingredients relevant to the origins of life. But did these molecules form in the solar system's protoplanetary disk, or were they inherited from the interstellar medium? The potential interstellar component in Oort Cloud material makes this question especially tantalizing. If 90% of Oort Cloud objects came from other stars, a pristine comet might carry chemical signatures from multiple stellar environments.

"The UK has played a leading role in designing the mission, with £16 million of national funding from the UK Space Agency planned, complementing mandatory ESA contributions."

- UK Space Agency

While Comet Interceptor is fundamentally a science mission, its operational concept has applications beyond studying ancient ice. The ability to pre-position a spacecraft and rapidly intercept a newly discovered object is exactly what you'd need for planetary defense - tracking and potentially deflecting an asteroid or comet on a collision course with Earth.

Interstellar objects present an even more intriguing case. When 'Oumuamua zipped through the solar system in 2017, we had no spacecraft ready to chase it. It came and went in weeks, leaving astronomers with telescopic observations and a pile of unanswered questions. A future interstellar visitor could be intercepted by a mission using Comet Interceptor's playbook: wait at L2, detect the intruder early, and execute a rapid intercept.

The ESA-JAXA partnership on this mission also demonstrates how international collaboration enables ambitious projects neither agency could afford alone. JAXA's contribution of Spacecraft B1 adds a probe without doubling ESA's costs, while JAXA gains participation in a high-profile mission. The UK's £16 million investment buys scientific leadership through the Interdisciplinary Scientist role held by Professor Snodgrass and principal investigator positions on key instruments. It's a model for future fast-response missions that require quick development and international buy-in.

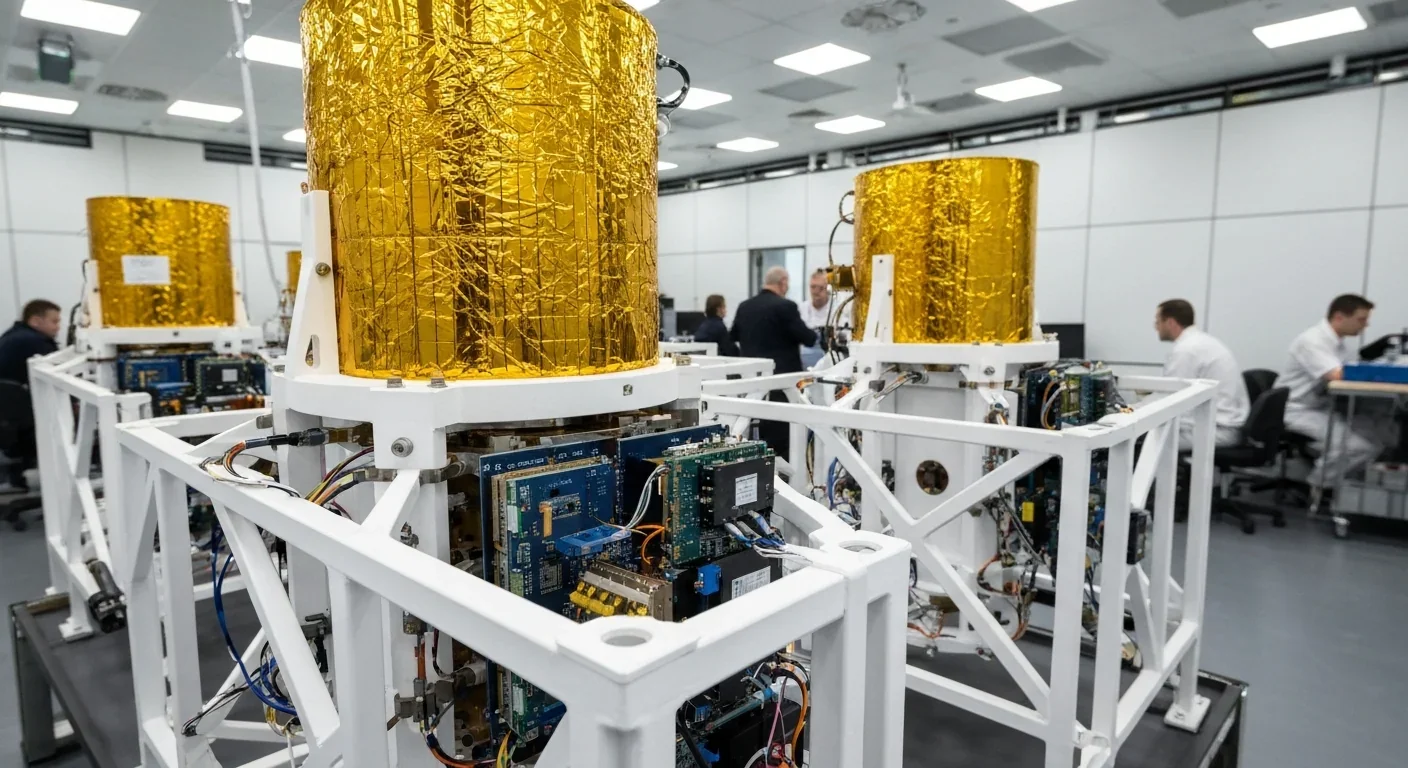

As of early 2026, Comet Interceptor is in development following its adoption by ESA in June 2022. Instruments are being built and tested. Spacecraft designs are being finalized. Launch contracts are being negotiated. And somewhere in the outer reaches of the solar system, a frozen chunk of ice and rock - older than the planets, possibly older than the Sun itself - is beginning its long fall toward the inner solar system.

When that comet arrives, we'll be ready. Three silent sentries will be waiting at L2, patient and alert, ready to wake from dormancy and race toward an appointment made 4.6 billion years in the making.

The mission's gamble is simple but audacious: bet that ground-based surveys will find a suitable target within a reasonable timeframe. Bet that engineering can create spacecraft capable of waiting indefinitely and acting decisively. Bet that a single close encounter with a pristine comet will answer questions we haven't been able to resolve with decades of studying altered ones.

As the Universe Today article notes, it's "a risk that makes most inveterate gamblers blush". But the potential payoff - understanding where we came from, how the solar system formed, and what role interstellar material played in Earth's habitability - justifies the wait.

The mission must balance finding a comet active enough to be scientifically interesting but calm enough not to destroy the delicate probes during flyby.

In an era where space exploration often feels like a race to get somewhere first, Comet Interceptor offers a different philosophy: sometimes the best strategy is to position yourself strategically and wait for the universe to deliver something extraordinary. Three spacecraft, parked in the void, patient and ready, waiting for a comet that hasn't seen sunlight since the solar system was born.

The countdown is already ticking. Not toward launch - that's just logistics. The real countdown is cosmic: how long until a pristine messenger from the outer darkness appears, and how quickly can we intercept it before the Sun's warmth starts erasing the ancient chemistry we're desperate to read?

Soon, we'll find out if patience really is a virtue, or if three spacecraft will wait at L2 forever, staring into the darkness, hoping for a target that never comes.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

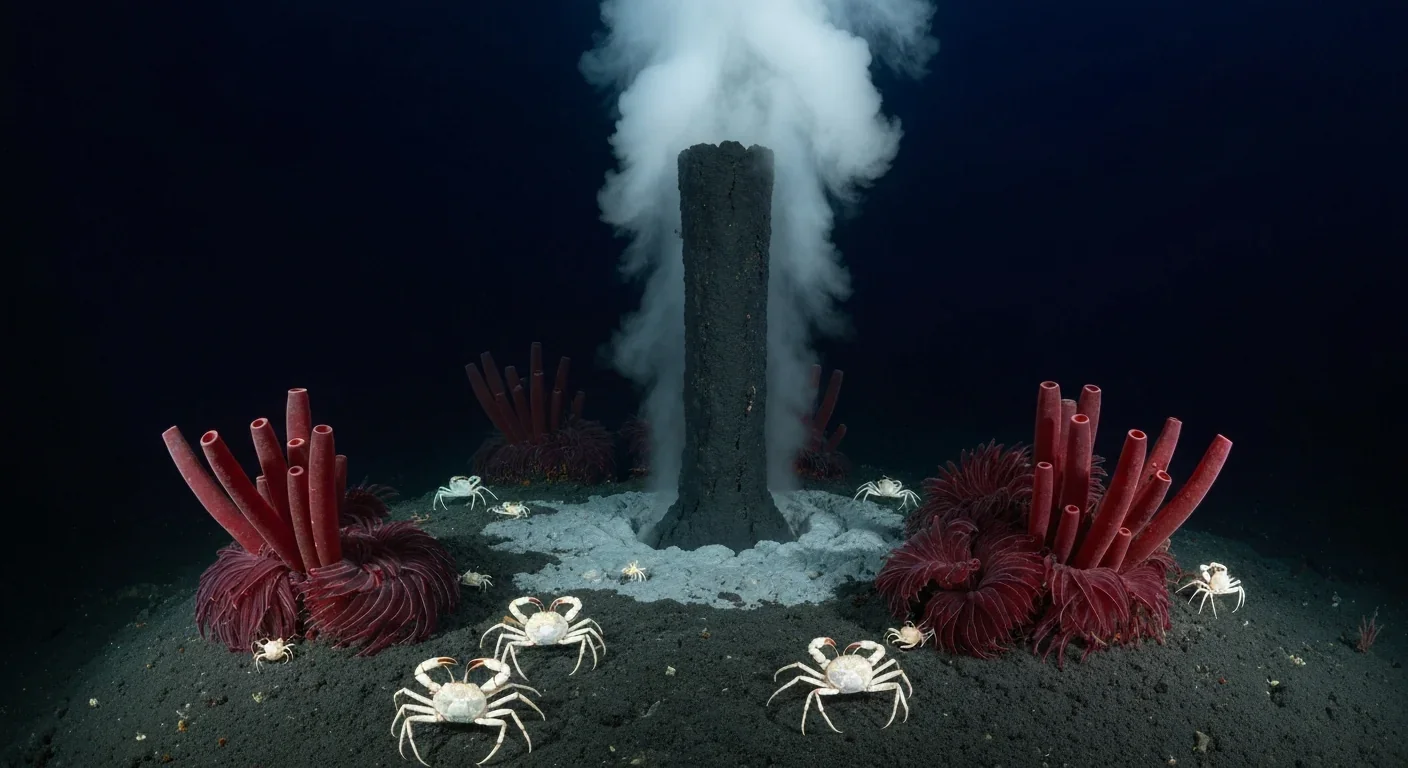

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.