Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: Scientists are developing breakthrough methods to detect Stephen Hawking's 50-year-old prediction that black holes emit faint radiation. New strategies include catching primordial black holes passing through our solar system and laboratory simulations using atomic chains. Success would unite quantum mechanics with relativity and potentially solve the dark matter mystery.

In 1974, Stephen Hawking proposed something that defied everything physicists thought they knew about black holes: these cosmic monsters weren't entirely black. They leaked. Faint particles should escape from their edges through quantum trickery, causing even the most massive black holes to eventually evaporate. Half a century later, despite being one of the most celebrated predictions in theoretical physics, Hawking radiation has never been directly detected from an actual black hole.

The problem? The signal is absurdly faint. A black hole with the mass of our Sun would emit radiation at a temperature a trillionth of a degree above absolute zero, completely drowned out by the cosmic microwave background that bathes the universe at a comparatively toasty 2.7 degrees Kelvin. Detecting that whisper would be like trying to hear someone exhale from across the solar system.

Yet scientists haven't given up. They're getting creative. New detection strategies, laboratory simulations, and space-based observatories are bringing us closer than ever to confirming Hawking's radical idea. If they succeed, it won't just validate one brilliant physicist's theory. It could crack open the door to quantum gravity, the holy grail theory that would finally unite Einstein's relativity with quantum mechanics and explain how reality actually works at its deepest level.

When Hawking published his groundbreaking calculation, it shook physics to its core. Black holes were supposed to be one-way streets to oblivion. Nothing escapes, not even light. That's what makes them black holes.

But Hawking showed that quantum mechanics changes everything near the event horizon. Particle-antiparticle pairs constantly pop into existence throughout empty space because of quantum fluctuations. Usually, these pairs immediately annihilate each other. Near a black hole's edge, though, one particle can fall in while the other escapes. To an outside observer, the black hole appears to emit radiation.

Hawking radiation emerges from quantum fluctuations at a black hole's event horizon, where particle-antiparticle pairs split and one escapes while the other falls in. This process causes black holes to slowly evaporate over astronomical timescales.

This seemingly simple process has profound implications. It means black holes have a temperature. They have entropy. They're thermodynamic systems that can lose mass and eventually evaporate entirely. For stellar-mass black holes, this would take longer than the current age of the universe by countless orders of magnitude. But for tiny primordial black holes that might have formed in the early universe, evaporation could happen on timescales we can actually work with.

More importantly, Hawking radiation sits at the intersection of quantum mechanics and general relativity. These two pillars of modern physics famously don't play well together. General relativity describes gravity as the curvature of smooth, continuous spacetime. Quantum mechanics describes reality as fundamentally probabilistic and discrete at the smallest scales. Every attempt to merge them into a theory of quantum gravity has hit mathematical walls.

Black holes are where this tension becomes unavoidable. They're massive enough that general relativity dominates, yet their event horizons are regions where quantum effects can't be ignored. Hawking radiation emerges from this collision. Detecting it would prove that our theories are on the right track and potentially reveal clues about how to build that elusive unified framework.

Trying to detect Hawking radiation from astronomical black holes faces a cascade of problems. The radiation is thermal, meaning it has a blackbody spectrum determined by the black hole's mass. The larger the black hole, the colder its radiation. For the supermassive black holes at galaxy centers, the temperature is so low that the radiation would be utterly invisible against the cosmic microwave background.

Only the smallest black holes would be hot enough to detect. Physicists have calculated that a black hole with about the mass of a small asteroid would have a Hawking temperature around room temperature. Go smaller, and the temperature rises dramatically. These hypothetical primordial black holes could have formed in the dense, chaotic moments after the Big Bang when random fluctuations created regions dense enough to collapse.

If primordial black holes exist in the mass range where their Hawking radiation is detectable, they could solve two mysteries at once. They might explain what dark matter actually is, that invisible stuff that makes up 85% of the universe's matter. And they'd give us a way to actually observe Hawking radiation in nature.

The catch? We don't know if primordial black holes exist, where they are, or how common they might be. Previous attempts to detect them focused on looking for subtle effects in cosmic ray backgrounds or searching for their gravitational signatures. These approaches require modeling complex astrophysical processes and extracting faint signals from noisy data.

A recent proposal offers a more direct approach that could actually work with technology we already have. Instead of scanning the cosmic background for faint signals, researchers led by Alexandra P. Klipfel suggest watching for individual primordial black holes as they pass through our solar system.

The idea is elegant. As a primordial black hole zips past Earth, instruments aboard the International Space Station could detect a temporary spike in positrons, the antimatter partners of electrons. The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, already collecting data on cosmic rays, measures positrons with enough sensitivity to spot the distinctive signature a passing black hole would produce.

"Simulations yield about one detectable PBH transit per year. This represents a dramatic improvement over current detection methods."

- Alexandra P. Klipfel et al., arXiv preprint

The beauty of this approach is its precision. Rather than trying to extract a signal from the jumbled cosmic background, scientists would look for a time-dependent event with a clear beginning, peak, and end. The passage time depends on the black hole's speed and distance, but the signature would be unmistakable if it happened.

Klipfel's team ran simulations and found that if primordial black holes make up a significant fraction of dark matter in the relevant mass range, we should see about one detectable transit per year. That's not a lot, but it's infinitely better than zero. A single confirmed detection would revolutionize cosmology. It would prove Hawking radiation exists, confirm primordial black holes are real, and provide direct evidence about what dark matter actually is.

The technique could extend beyond positrons, too. Gamma rays and X-rays from Hawking radiation could probe an even wider range of primordial black hole masses. As new space-based observatories come online with better sensitivity and time resolution, the chances of catching one of these elusive objects improve dramatically.

While astronomers hunt for cosmic signals, laboratory physicists are taking a completely different approach. They're building analog black holes that simulate event horizons without requiring actual gravitational collapse.

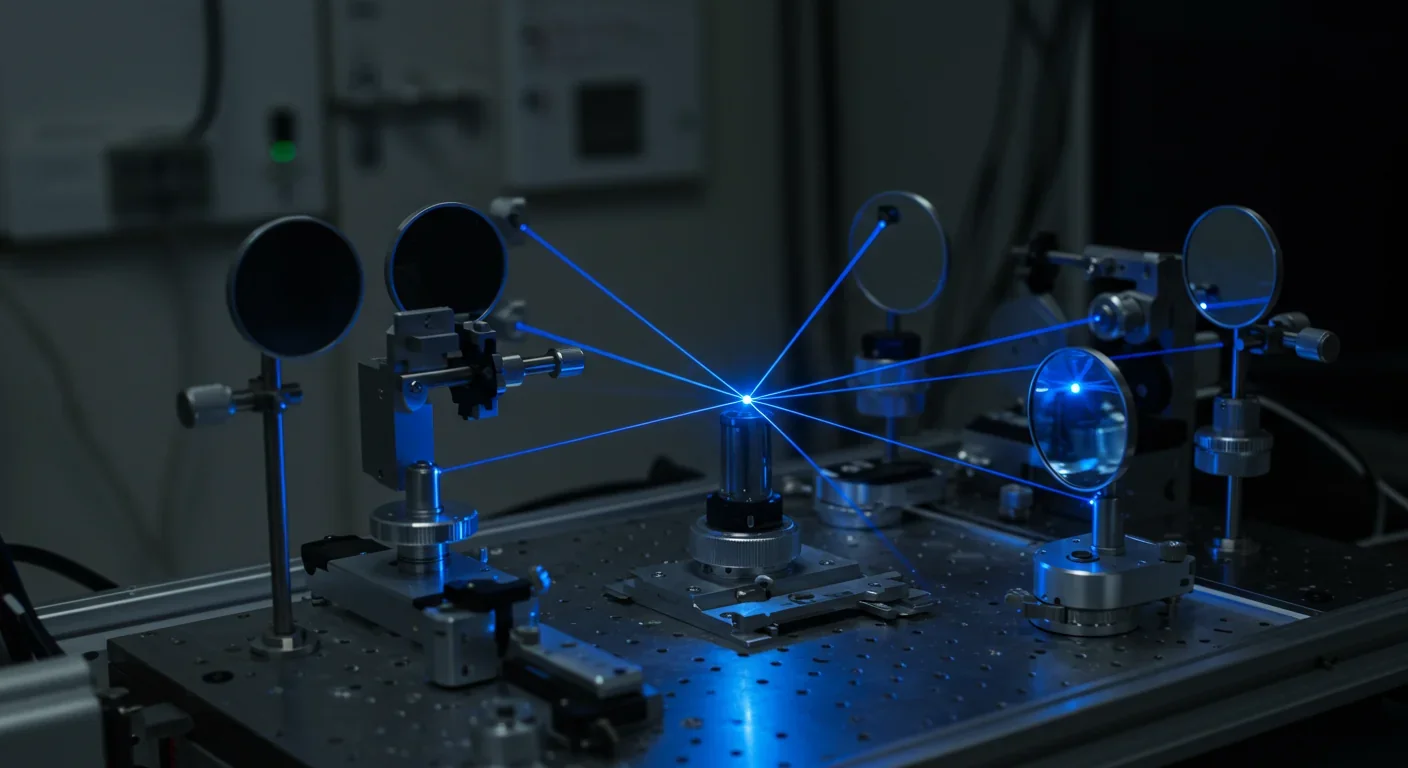

In 2022, a team led by Lotte Mertens at the University of Amsterdam created a synthetic event horizon using a one-dimensional chain of atoms. By controlling how easily electrons could hop between atomic positions, they created a boundary that mimicked the point of no return around a real black hole. The electron waves behaved exactly as Hawking's theory predicted, and the system produced thermal radiation analogous to Hawking radiation.

The experiment is clever because it sidesteps the impossible task of creating actual black holes in the lab. Instead, it exploits mathematical similarities between different physical systems. Quantum fields near a black hole's event horizon behave in ways that can be reproduced using completely different setups like flowing fluids, sound waves in exotic materials, or carefully tuned atomic chains.

These analog systems produce what's called Hawking-like radiation. It's not actual photons or particles emerging from curved spacetime around a gravitational singularity. But the underlying quantum mechanical processes are mathematically equivalent. The analogs let physicists test Hawking's predictions in controlled environments where they can tweak parameters and run experiments that would be impossible with real black holes.

Mertens' team found something intriguing: the simulated radiation only showed thermal properties under specific conditions. When the atomic chain extended beyond the synthetic event horizon, the system heated up as expected. But when they changed certain parameters, the thermal signature vanished. This suggests that particle entanglement across the event horizon might be crucial for generating Hawking radiation.

Laboratory analog systems can't prove real black holes emit Hawking radiation, but they validate the theoretical framework by demonstrating mathematically equivalent quantum phenomena in controlled settings.

Other groups have built similar analogs using different approaches. Researchers have created event horizon analogs in flowing fluids, where the fluid velocity creates a region that waves can't escape. They've used light pulses in fiber optics and quantum tornadoes in ultracold atomic gases. Each system offers unique advantages for testing different aspects of Hawking's theory.

These experiments can't directly prove that real black holes emit Hawking radiation. The analogy, while mathematically rigorous, isn't perfect. But they can validate the theoretical framework and reveal how quantum field behavior near horizons depends on different conditions. If the lab results match predictions, it builds confidence that the same physics applies to actual black holes.

Detecting Hawking radiation would answer one question but potentially deepen another. The black hole information paradox has tormented physicists since Hawking first proposed his radiation theory.

Here's the problem: quantum mechanics says information can't be destroyed. The complete quantum state of any system must be preserved, even if it becomes scrambled or hard to access. But if black holes evaporate via Hawking radiation, what happens to the information that fell in?

Hawking radiation is thermal, meaning it has no structure beyond its temperature. It's completely random, like the heat from a fire. If a black hole evaporates completely, turning all its mass into featureless thermal radiation, the information about everything that fell in appears to be lost forever. This directly violates quantum mechanics' fundamental principle.

"If the radiation turns out to carry information through subtle quantum correlations, it would vindicate the information preservation camp and point toward a consistent theory of quantum gravity."

- Current theoretical consensus in quantum gravity research

Hawking initially thought information was indeed destroyed, implying quantum mechanics breaks down for black holes. Others, including Leonard Susskind, argued the information must somehow be encoded in the radiation itself, perhaps through subtle correlations that only become apparent over long timescales. This debate raged for decades and spawned entire subfields of theoretical physics.

Recent theoretical work suggests possible resolutions. Some physicists propose that information leaks out gradually through quantum corrections to Hawking's original calculation. Others invoke ideas like black hole complementarity or the holographic principle, which reimagines black hole physics in radical ways.

Detecting actual Hawking radiation and measuring its properties in detail could finally settle this question. If the radiation turns out to carry information through subtle quantum correlations, it would vindicate the information preservation camp and point toward a consistent theory of quantum gravity. If the radiation really is purely thermal, physics would face a genuine crisis that demands revolutionary new ideas.

Even with clever new strategies, detecting Hawking radiation remains extraordinarily difficult. The positron detection approach requires not just sensitive instruments but also sophisticated data analysis to distinguish genuine black hole transits from instrumental noise and other astrophysical sources.

Current space-based detectors like the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer collect mountains of data on cosmic rays and high-energy particles. Identifying the needle of a primordial black hole signal in that haystack demands careful modeling of expected signatures and aggressive filtering of backgrounds.

The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and upcoming observatories like the Cherenkov Telescope Array could search for gamma-ray signatures from evaporating primordial black holes. These instruments have the sensitivity to detect bursts from exploding micro black holes, if such objects exist and happen to evaporate within our observational reach.

Researchers are also exploring whether primordial black holes might leave fingerprints in other astronomical data. Radio telescopes like the Square Kilometre Array could potentially detect signatures in the 21-centimeter hydrogen line from the cosmic dawn era. Gravitational wave detectors might spot primordial black hole collisions. Each approach offers complementary windows into this hidden population.

On the laboratory side, analog experiments continue to grow more sophisticated. Researchers are building systems that better capture the dynamical aspects of black hole formation and evaporation, not just the static properties of event horizons. These experiments might reveal subtle features of Hawking radiation that pure theory hasn't predicted.

But even if we detect Hawking radiation tomorrow, many questions would remain. Exactly how does information escape from black holes? Do quantum corrections significantly modify the radiation spectrum? What happens to the black hole at the very end of evaporation, when it becomes so small that quantum effects completely dominate?

The quest to detect Hawking radiation isn't just about ticking off a prediction from 1974. It's about understanding the deepest structure of reality.

Quantum mechanics and general relativity are our two most successful theories, each validated by countless experiments. Yet they describe fundamentally incompatible pictures of reality. Quantum mechanics says the universe is probabilistic, discrete, and observer-dependent at small scales. General relativity says spacetime is deterministic, continuous, and observer-independent everywhere.

This tension is usually ignorable. Quantum effects matter for atoms and subatomic particles, where gravity is negligibly weak. Gravitational effects matter for planets and stars, where quantum fuzziness averages out. But black holes force both into the same arena.

A theory of quantum gravity would unite Einstein's relativity with quantum mechanics, finally explaining how reality works at its deepest level. Hawking radiation offers one of the few observable windows into this fundamental frontier.

A theory of quantum gravity would show how these seemingly incompatible descriptions emerge from a deeper framework. String theory, loop quantum gravity, and other approaches each offer potential paths, but none has achieved experimental confirmation.

Hawking radiation provides one of the few observable windows into quantum gravity. Its properties encode information about how quantum fields behave in curved spacetime, how event horizons work at the quantum level, and how information flows in extreme conditions. Measuring these properties could rule out some quantum gravity theories and point toward others.

Beyond the technical physics, confirming Hawking radiation would complete a conceptual revolution. Black holes have always symbolized the ultimate cosmic prison, regions where the normal rules break down and nothing escapes. Showing they actually glow, evaporate, and participate in the larger quantum universe transforms them from dead ends into dynamic participants in cosmic evolution.

It would also vindicate one of the most audacious theoretical predictions ever made. Hawking derived his result through pure mathematics, combining general relativity and quantum field theory without any experimental guidance. For 50 years, we've believed that calculation based largely on its mathematical elegance and consistency. Actually seeing the phenomenon happen would demonstrate the power of theoretical physics to reveal truths about nature that can't yet be directly observed.

We're entering a golden age for black hole physics. Gravitational wave detectors have opened a new window on black hole collisions. The Event Horizon Telescope has imaged black hole shadows. Space-based observatories are surveying the high-energy sky with unprecedented sensitivity.

Within the next decade, several promising detection strategies will reach maturity. The positron transit method will have collected enough data to either confirm primordial black hole passages or place tight constraints on their abundance. Gamma-ray observatories will have scanned enough of the sky to potentially catch an evaporating black hole's death rattle. Laboratory analogs will have tested Hawking's theory under a wide range of conditions.

If any of these efforts succeeds, it will trigger an explosion of follow-up research. Detailed measurements of the radiation spectrum could reveal quantum corrections to Hawking's original calculation. Multiple detections could map out the mass distribution of primordial black holes and confirm or rule out their role as dark matter. Laboratory experiments could probe increasingly subtle aspects of how quantum fields behave near horizons.

Even null results would teach us something. If we don't detect primordial black holes despite sensitive searches, it constrains models of the early universe and points dark matter research in other directions. If analog experiments show deviations from theory, it might hint at new physics beyond our current frameworks.

The hunt for Hawking radiation has already transformed our understanding of black holes from static solutions in Einstein's equations to dynamic thermodynamic systems that live and die. Actually catching that faint whisper from the edge of a cosmic abyss would bring the picture full circle, turning theoretical elegance into observable reality.

And it would mark the moment when humanity finally glimpsed the quantum nature of gravity itself, fifty years after Hawking first told us it was there.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.