Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: Giant molecular clouds spanning light-years collapse under gravity over millions of years to form protostars, protoplanetary disks, and eventually complete solar systems. Recent JWST and ALMA observations reveal this spectacular process in unprecedented detail, showing how our own 4.6-billion-year-old solar system formed.

In the cold darkness between stars, colossal clouds of hydrogen and dust drift silently across light-years of space. These vast stellar nurseries, some containing enough material to build 10 million suns, hold the secret to one of the universe's most fundamental transformations: the birth of stars and planets. Right now, across the cosmos, gravity is sculpting these frozen clouds into the next generation of solar systems. The same process that created our own sun 4.6 billion years ago continues today, and thanks to revolutionary observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, we're finally witnessing this spectacular cosmic drama in unprecedented detail.

Understanding how stars form isn't just abstract astrophysics. It's the origin story of everything we know, from the elements in our bodies to the planets beneath our feet. Each new solar system that ignites represents billions of years of potential evolution, possibly leading to worlds teeming with life.

Giant molecular clouds are the womb of the galaxy. These sprawling structures, scattered throughout the Milky Way and other galaxies, contain between 100,000 and 10 million times the mass of our sun. Yet despite their immense mass, they're incredibly diffuse and extraordinarily cold, hovering at temperatures around 10 to 20 Kelvin (roughly -440°F).

At such frigid temperatures, hydrogen molecules move sluggishly, allowing gravity to gain the upper hand. The clouds span hundreds of light-years, with densities so low they'd qualify as a vacuum by Earth standards. But in the context of interstellar space, they're dense enough for gravity to begin its patient work.

The Orion Molecular Cloud Complex, located just 1,500 light-years from Earth, offers astronomers a front-row seat to active star formation. Through telescopes, this stellar factory glows with the infrared signatures of hundreds of protostars at various stages of development. It's a laboratory where we can study the process that created our own solar system.

Only about 1 to 3 percent of a molecular cloud's mass actually converts into stars during each collapse cycle - magnetic fields and turbulence prevent the rest from falling inward, making star formation surprisingly inefficient.

Molecular clouds can drift peacefully for millions of years before something tips them over the edge into collapse. So what pulls the trigger? Scientists have identified several mechanisms that can disturb a cloud's delicate balance and initiate the cascade toward star formation.

Supernova shockwaves provide one of the most dramatic triggers. When a massive star explodes, it sends a powerful blast wave rippling through space at thousands of kilometers per second. This compression can squeeze nearby molecular clouds, creating density pockets that become gravitationally unstable.

Galaxy collisions offer another spectacular trigger mechanism. When two galaxies merge, their respective molecular clouds collide at cosmic velocities, compressing gas and sparking massive bursts of star formation. Astronomers observe these "starburst galaxies" producing new stars at rates hundreds of times faster than our relatively quiet Milky Way.

Even without external triggers, molecular clouds contain their own destabilizing forces. Turbulence created by stellar winds, magnetic field irregularities, and simple gravitational instabilities can cause regions within a cloud to become denser than their surroundings. Once a clump reaches a critical mass, known as the Jeans mass, gravity overwhelms the internal pressure and collapse begins.

As a cloud region begins to collapse, three fundamental forces engage in a complex choreography that determines the final architecture of the emerging solar system: gravity, magnetic fields, and angular momentum.

Gravity is the director of this cosmic ballet, pulling material inward with relentless force. But it doesn't work alone. Magnetic fields threading through molecular clouds can be surprisingly strong, reaching 10 to 100 microgauss. Though that sounds weak compared to Earth's magnetic field, across light-years of space these fields exert significant pressure, sometimes slowing or even preventing collapse.

This magnetic resistance helps explain a puzzle that bothered astronomers for decades: why star formation is so inefficient. Only about 1 to 3 percent of a molecular cloud's mass actually converts into stars per collapse cycle. The rest either gets blown away by stellar winds or remains in the cloud, supported against gravity by magnetic pressure and turbulent motions.

Angular momentum introduces another constraint. Every molecular cloud has some rotation, however slight. As material collapses inward, conservation of angular momentum causes it to spin faster, like an ice skater pulling in their arms. This rotation prevents all the material from falling straight into the center. Instead, it forms a swirling disk around the developing protostar.

"The balance between gravity, magnetic fields, and rotation is delicate. Small variations in initial conditions can produce dramatically different planetary systems, explaining the extraordinary diversity we observe around other stars."

- Recent research from ALMA observations

Recent research using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) has revealed intricate details of these collapsing systems. Astronomers can now observe magnetic field lines bending and twisting as material spirals inward, watch turbulent eddies distribute angular momentum, and track how the competing forces sculpt the emerging disk structure.

The actual birth of a star is a gradual process spanning millions of years. It begins when a collapsing clump becomes opaque to infrared radiation, trapping heat inside. This marks the formation of a protostar, a warm embryonic object not yet capable of nuclear fusion.

As the protostar continues to accrete material from the surrounding cloud, it grows hotter and denser. The journey for a sun-like star takes 10 to 50 million years from initial collapse to full ignition. During this period, the protostar remains hidden within its dusty cocoon, visible only at infrared and radio wavelengths.

The protostar's core steadily increases in temperature and pressure. When the core finally reaches approximately 10 million Kelvin, hydrogen nuclei begin fusing into helium. This moment of first light marks the true birth of a star. The sudden flood of energy from fusion creates an outward radiation pressure that halts further collapse, stabilizing the star in a delicate balance between gravity pulling inward and fusion pressure pushing outward.

This balance will persist for billions of years. Our own sun has maintained this equilibrium for 4.6 billion years and will continue for another 5 billion before exhausting its hydrogen fuel.

While the central star forms, the swirling disk of material around it becomes a factory for planets. These protoplanetary disks typically contain between 0.001 and 0.1 solar masses of gas, dust, and ice, all orbiting the young star in the same direction.

Within the disk, dust grains collide and stick together through electrostatic forces and gentle collisions. These aggregates grow from microscopic particles to pebbles, then to boulders, and eventually to planetesimals, rocky or icy bodies kilometers across. Gravity takes over at this scale, allowing planetesimals to sweep up nearby material and grow into full-fledged planets.

The disk isn't uniform. Temperature gradients create distinct zones where different materials can condense. Close to the star, where temperatures are high, only rocks and metals can survive in solid form. This is where rocky planets like Earth and Mars form. Farther out, beyond the "frost line" where water can freeze, icy materials become available, allowing the formation of gas giant cores that can gravitationally capture enormous atmospheres of hydrogen and helium.

The formation and evolution of our own solar system followed this pattern 4.6 billion years ago. The sun formed at the center while the eight planets, dozens of moons, and countless asteroids and comets assembled in the surrounding disk. The entire process, from initial cloud collapse to a recognizable solar system, took roughly 100 million years.

Temperature gradients within protoplanetary disks create a "frost line" that determines planetary composition. Inside this line, only rock and metal survive, creating terrestrial planets. Beyond it, ice enables the formation of gas giants.

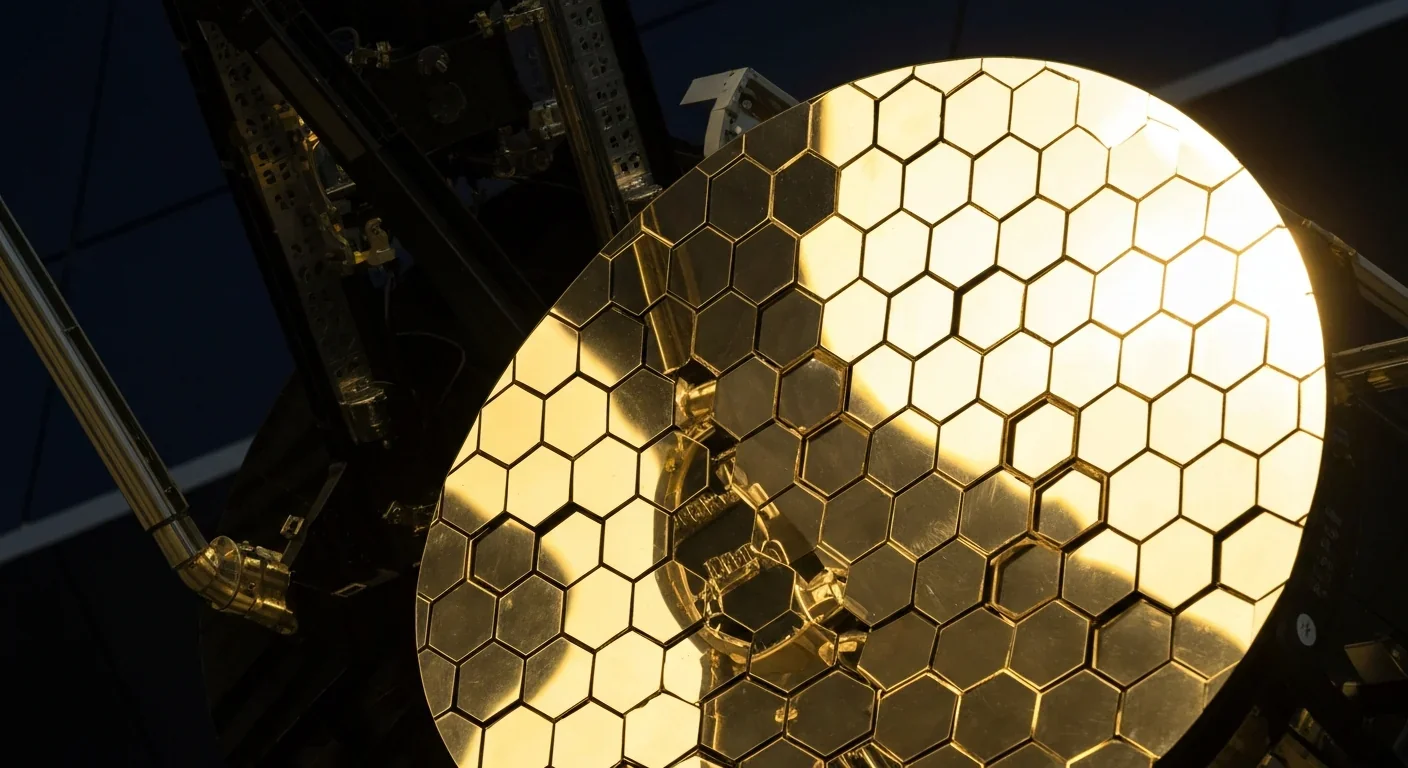

The past few years have revolutionized our understanding of star formation, thanks largely to two extraordinary observatories: the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA).

JWST, launched in 2021, peers through dusty clouds with unprecedented infrared sensitivity. In 2022 and 2023, it captured stunning images of protostars still embedded in their natal clouds, revealing bipolar jets of material shooting out from the poles at hundreds of kilometers per second. These jets help remove angular momentum from the system, allowing more material to fall onto the growing star.

One remarkable JWST observation showed a protoplanetary disk with clear gaps and rings, the telltale signatures of planets already forming while the star itself was barely a few million years old. This suggests planet formation begins even earlier than previously thought, possibly starting while the protostar is still accreting material.

ALMA, operating from Chile's Atacama Desert, complements JWST by observing at millimeter wavelengths. This allows it to map the cold dust and gas in protoplanetary disks with exquisite detail. Recent ALMA observations have revealed spiral density waves, asymmetric structures, and shadows cast by warped inner disk regions, all providing clues about how planets disturb their birth environments.

In 2024, astronomers using JWST announced they may have detected signatures of Population III stars, the very first generation of stars that formed in the early universe from clouds containing only hydrogen and helium. These primordial stars, if confirmed, represent star formation in its purest form, before heavy elements from supernovae enriched the cosmos.

The final architecture of a solar system - how many planets it has and where they orbit - depends critically on the interplay between several competing forces during formation.

Gravity drives collapse and accretion, but turbulence within the cloud can fragment it into multiple collapsing regions, creating binary or multiple star systems rather than solitary stars. In fact, most stars in our galaxy are born in pairs or groups, making our single sun somewhat unusual.

Magnetic fields thread through the collapsing material, coupling to charged particles and creating magnetic drag. This drag can transport angular momentum outward, allowing material to move inward. Recent simulations show that without this magnetic braking mechanism, protoplanetary disks would retain too much angular momentum and stars would struggle to accrete enough mass.

Stellar winds and radiation pressure from the newborn star gradually disperse the protoplanetary disk. This sets a timer on planet formation: planets must assemble before the disk dissipates, typically within 1 to 10 million years. Any planets that haven't fully formed by then will remain as smaller bodies - asteroids and comets that never achieved full planetary status.

The balance between these forces is delicate. Small variations in initial conditions, such as the cloud's rotation rate, magnetic field strength, or level of turbulence, can produce dramatically different outcomes. This helps explain the extraordinary diversity of planetary systems discovered around other stars: hot Jupiters orbiting closer to their stars than Mercury orbits our sun, super-Earths with no analog in our solar system, and planets on wildly eccentric orbits unlike anything in our relatively orderly solar system.

Once a star achieves fusion ignition, it dramatically transforms its environment. The flood of ultraviolet radiation and powerful stellar winds blow away remaining gas in the protoplanetary disk, revealing the newly formed planets. This marks the transition from star formation to stellar evolution.

Young stars can be violent. Many exhibit powerful flares and emit intense radiation that can strip away atmospheres from nearby planets. This radiation also ionizes any remaining disk material, creating photon-dominated regions where the physics is governed by the star's light rather than by gravity or magnetic fields.

The stellar nursery itself begins to disintegrate. The most massive stars, which evolve quickly, soon explode as supernovae. These explosions inject energy into the molecular cloud, heating and dispersing it. Ironically, the very process of star formation contains the seeds of the nursery's destruction. The stellar feedback from winds and supernovae eventually blows the molecular cloud apart, ending star formation in that region.

But the cycle continues. The material ejected by dying stars, enriched with heavy elements forged in their cores and supernova explosions, mixes into the interstellar medium. Eventually, this enriched material will collapse again to form a new generation of stars and planets, slightly richer in heavy elements than the previous generation.

"We are made of stardust. The atoms in your body were forged in long-dead stars, testifying to billions of years of cosmic recycling."

- Astrophysics consensus

Our solar system is the product of several such cycles. The atoms in your body, forged in long-dead stars, testify to this cosmic recycling. We are, quite literally, made of stardust.

Piecing together the history of our solar system's formation requires detective work across multiple lines of evidence: meteorite compositions, planetary orbits, crater records, and computer simulations.

The story begins 4.6 billion years ago in a molecular cloud region probably disturbed by a nearby supernova. Evidence for this trigger comes from meteorites containing short-lived radioactive isotopes that could only have been produced in a supernova and injected into our solar nebula within a few million years of their creation.

The collapsing cloud formed a rotating disk with the proto-sun at its center. Within a few million years, Jupiter and Saturn had formed in the outer solar system, their powerful gravity stirring up the remaining planetesimals. This gravitational churning scattered some planetesimals inward and others outward, some even ejecting into interstellar space.

The inner solar system took longer to finalize. Earth and the other rocky planets continued accreting for 30 to 100 million years after initial collapse. Earth's moon formed from debris after a Mars-sized body collided with the young Earth about 4.5 billion years ago, one of countless violent collisions that characterized the early solar system.

By about 4 billion years ago, the architecture we recognize today was largely in place. The gas disk had dissipated, planet formation had ceased, and the remaining debris was slowly cleared through collisions and gravitational ejections. The heavy bombardment period finally ended around 3.8 billion years ago, allowing stable conditions for life to emerge on Earth.

Understanding star and planet formation directly impacts the search for life beyond Earth. Every detail we learn about how planetary systems assemble helps us predict where habitable worlds might exist.

We now know that planet formation is robust and nearly universal. Surveys suggest most stars host planets, with Earth-sized worlds being particularly common. But having a planet in the habitable zone, where liquid water can exist, is just the first requirement for life.

The process of formation determines a planet's composition, atmosphere, and ability to retain water. Planets that form too close to their stars may never acquire water. Those that form too far out might migrate inward through gravitational interactions, becoming "hot Jupiters" that destroy any inner rocky planets in their path.

The star's own properties matter too. Its mass determines how long it will shine steadily, its radiation output affects planetary atmospheres, and its frequency of flares can sterilize nearby worlds. All these properties trace back to the initial molecular cloud collapse and the interplay of forces during formation.

Recent discoveries of planets around stars very different from our sun - from tiny red dwarfs to massive blue giants - show that planet formation can occur under a wide range of conditions. This expands the potential habitable zone of our galaxy and increases the odds that life has emerged elsewhere.

The next generation of observatories promises even more detailed views of stellar birth. The Extremely Large Telescope, under construction in Chile, will have a mirror 39 meters across, dwarfing current telescopes. It will resolve protoplanetary disks in unprecedented detail, potentially imaging individual planets as they form.

NASA's proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory, planned for the 2040s, will directly image Earth-like exoplanets and analyze their atmospheres for biosignatures. Understanding how these worlds formed will be crucial for interpreting any signs of life we might detect.

Theoretical advances continue as well. Modern supercomputers can now simulate the entire collapse process, from cloud to planetary system, following the evolution of millions of particles over millions of simulated years. These simulations reveal details impossible to observe directly, like the internal structure of turbulent eddies or the exact mechanism of magnetic field amplification.

The intersection of observation and theory is creating a comprehensive picture of star formation, one of the universe's most fundamental processes. Each new discovery refines our understanding of how gravity, magnetism, turbulence, and radiation collaborate to transform diffuse clouds into the stars and planets that populate the cosmos.

Star formation represents creation in its most literal sense: the birth of new worlds and the forging of the elements necessary for life. When we look at stellar nurseries through our telescopes, we're watching the same process that created our own sun, our Earth, and ultimately ourselves.

The journey from cold molecular cloud to functioning solar system spans millions of years and involves a delicate balance of forces. Gravity initiates the collapse, angular momentum shapes it into a disk, magnetic fields regulate the inflow of material, and turbulence determines whether the cloud fragments into multiple stars or forms a single system.

Thanks to observatories like JWST and ALMA, we're no longer limited to theoretical understanding. We can now watch protostars grow, see planets carving gaps in dusty disks, and observe stellar winds dispersing the last remnants of natal clouds. These observations confirm that our solar system's formation wasn't unique but rather an example of a universal process playing out across the galaxy.

As our instruments improve and our theories sharpen, we edge closer to answering fundamental questions: How common are solar systems like ours? What conditions are necessary for Earth-like planets to form? Where else might life have emerged from stellar nurseries?

The answers are being written in the clouds, waiting for us to decipher them. Every molecular cloud in the galaxy holds the potential for new solar systems, new planets, and perhaps new life. The spectacular physics of star birth continues, as it has for billions of years, creating the future of the cosmos one protostar at a time.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.