Spectacular Flares From the Milky Way's Black Hole

TL;DR: Io, Jupiter's moon, hosts over 400 active volcanoes powered by tidal heating from its orbital dance with Europa and Ganymede. Its surface renews every few thousand years through volcanic activity 30 times more intense than Earth's, providing crucial insights into planetary evolution and potentially habitable ocean worlds throughout the universe.

Deep within our solar system, a moon tears itself apart. Every second, Jupiter's gravity rips through Io's rocky interior, generating enough heat to melt stone and blast sulfur plumes 500 kilometers into space. With over 400 active volcanoes reshaping its surface constantly, Io represents the most geologically violent body we've ever observed. The discovery challenges everything we thought we knew about planetary evolution and opens startling possibilities for volcanic worlds orbiting distant stars.

Io didn't choose this fate. Trapped in a gravitational tug-of-war between Jupiter and its neighboring moons Europa and Ganymede, Io follows an elliptical orbit that varies its distance from the gas giant by thousands of kilometers. This orbital dance causes tidal forces that flex Io's interior like a stress ball squeezed in a giant's fist. The result? Internal friction generates heat exceeding anything radioactive decay alone could produce.

The numbers are staggering. Io's surface heat flux exceeds 2 watts per square meter, roughly 30 times Earth's geothermal output. Jupiter's tidal pull creates vertical differences in Io's tidal bulge of up to 100 meters between the closest and farthest points in its orbit. That's like the entire moon breathing in and out, inhaling and exhaling rock.

Every orbit, friction from this constant flexing melts the interior. The heat has to go somewhere. It erupts.

Io's surface heat flux exceeds 2 watts per square meter - roughly 30 times greater than Earth's geothermal output. This extreme energy release reshapes the entire surface every few thousand years.

Stand on Io's surface and you'd witness geology in fast-forward. The volcanic resurfacing happens at a rate of 0.1 to 1.0 centimeters per year, which means the entire surface gets buried under new material every few thousand years. Earth takes millions of years to achieve what Io accomplishes in millennia.

The proof is in what's missing. Impact craters - those ancient scars that mark the surfaces of nearly every planetary body - are virtually absent on Io. Fresh lava flows and sulfurous deposits bury them almost as quickly as they form. Observations by Voyager, Galileo, Cassini, New Horizons, and Juno have revealed this relentless resurfacing in action.

Compare that to Earth, where volcanic activity concentrates along tectonic plate boundaries and hotspots. Io has no plates, no continental drift, no ocean floors spreading apart. Just pure, concentrated tidal fury distributed across hundreds of volcanic centers. It's planetary geology stripped to its most primal form.

Linda Morabito was analyzing navigation images from Voyager 1 in 1979 when she noticed something odd. A plume extended 300 kilometers above Io's limb, visible only because she'd adjusted the image contrast. That moment - that single photograph - rewrote planetary science. Before Voyager, scientists assumed small moons were geologically dead. Io proved them spectacularly wrong.

Since then, every spacecraft visiting the Jovian system has trained its instruments on this volcanic hellscape. Galileo captured eruption temperatures exceeding 1,600 Kelvin - hot enough to melt rock into ultramafic silicate lavas similar to Earth's ancient komatiites. New Horizons observed Tvashtar volcano's 330-kilometer-high plume in 2007, depositing a red sulfur ring 1,200 kilometers wide.

But Juno's recent discoveries surpass them all. During a December 2024 flyby, Juno's infrared instrument detected a massive hot spot so powerful it saturated the detector. The feature spans 100,000 square kilometers - more than five times larger than Loki Patera, previously considered Io's most powerful volcano. The total power output measured above 80 trillion watts.

"JIRAM detected an event of extreme infrared radiance - a massive hot spot - in Io's southern hemisphere so strong that it saturated our detector."

- Alessandro Mura, Juno co-investigator

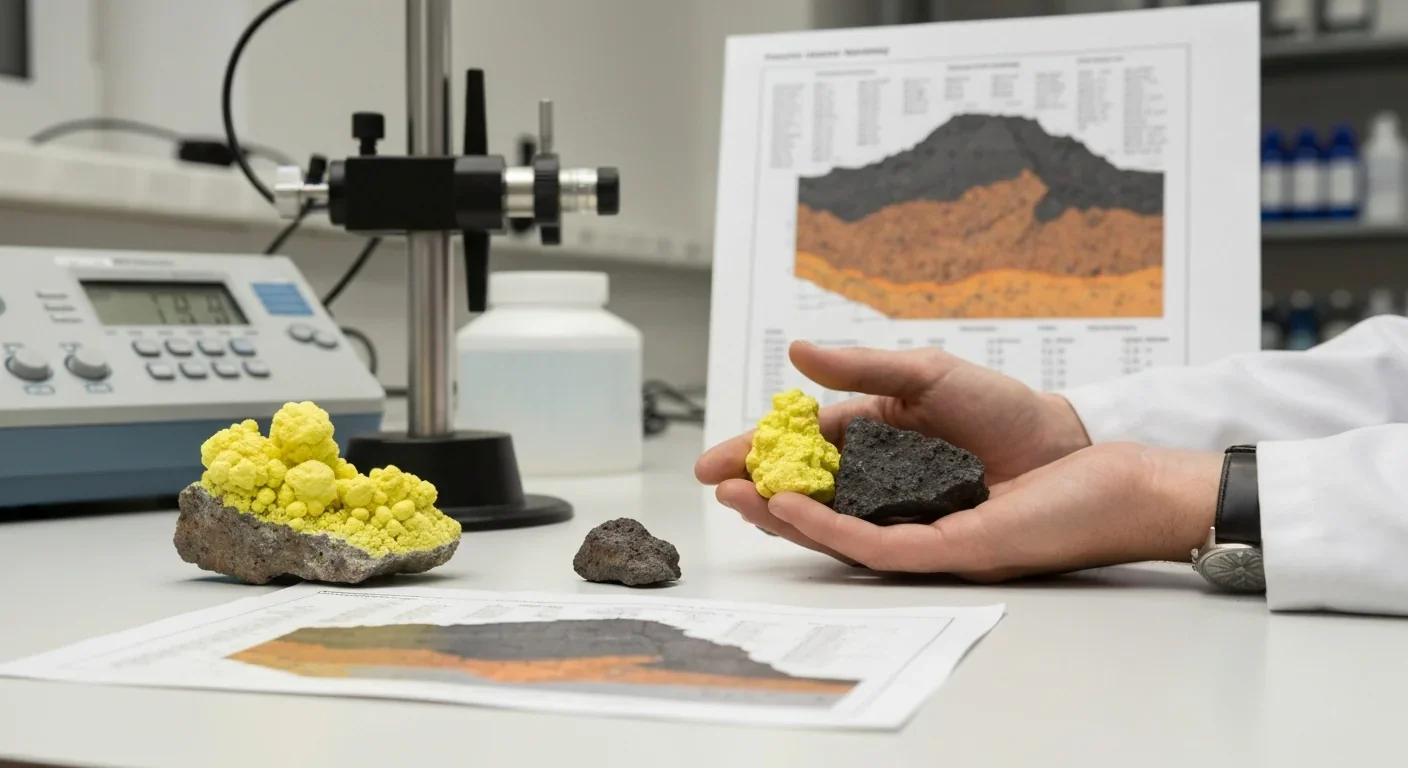

Io's volcanoes don't just erupt basalt. Sulfur and sulfur dioxide create an exotic volcanic chemistry unlike anything on Earth. Some eruptions shoot pure molten sulfur onto the surface, painting the moon in yellows, oranges, and reds. Others blast silicate lava at temperatures that would vaporize most terrestrial rocks.

NASA's Atacama Large Millimeter Array observations revealed that Io has lost between 94% and 99% of its primordial sulfur inventory over its history. The isotope ratios tell a story of billions of years of volcanic outgassing, with lighter isotopes preferentially escaping to space while heavier ones concentrate in the remaining atmosphere and surface materials.

The detection of sodium and potassium chlorides in Io's atmosphere suggests even more complex chemistry. These salts, ejected by volcanic vents, indicate that subsurface processes can produce compounds beyond simple sulfur and silicate systems. Ground-based telescopes and JWST imaging continue to track these atmospheric changes, revealing how volcanic emissions shape the thin exosphere surrounding this tortured world.

The largest volcanic plumes on Io achieve heights that dwarf anything on Earth. Pele-type plumes reach altitudes of 300 to 500 kilometers, ejecting sulfur dioxide and other volatiles at velocities approaching one kilometer per second. At those speeds, particles escape Io's weak gravity and flow directly into Jupiter's magnetosphere.

This creates a massive plasma torus around Jupiter - a doughnut-shaped cloud of ionized particles fed continuously by Io's volcanic activity. The volcanic plumes inject significant amounts of ionized sulfur and oxygen into this magnetospheric structure, influencing Jupiter's auroral emissions and plasma dynamics. Io essentially acts as a cosmic fire hose, spraying charged particles into Jupiter's magnetic field.

Scientists classify Io's plumes into two types. Prometheus-type plumes result from sulfur dioxide snow sublimating when hot lava flows over it. Pele-type plumes come from direct volcanic venting, powered by gas expansion from molten rock. Both types create spectacular umbrella-shaped deposits visible even from Earth-based telescopes.

Io's volcanic plumes reach heights of 300 to 500 kilometers - more than 30 times higher than Earth's tallest volcanic eruption columns. Material ejected at these speeds escapes directly into Jupiter's magnetosphere.

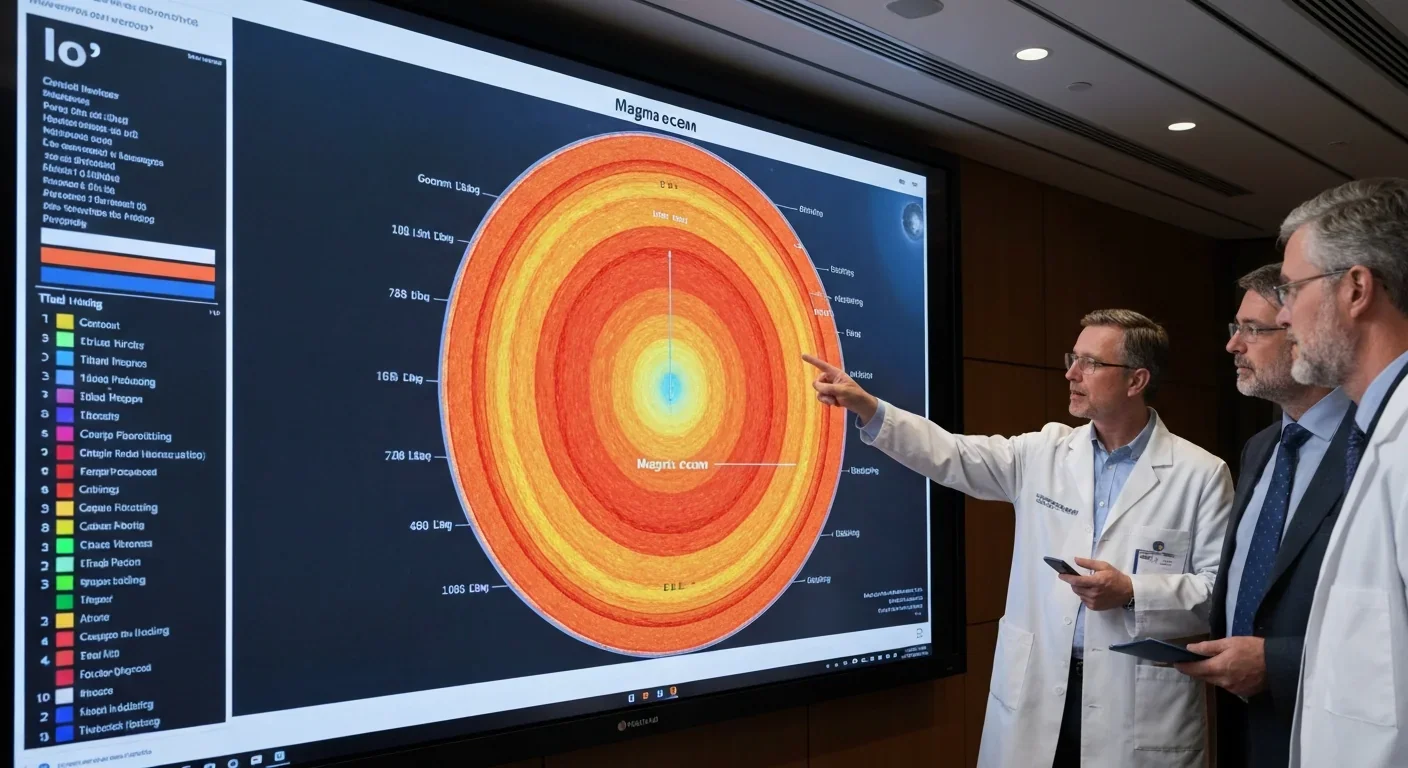

Evidence suggests that Io harbors something even more extraordinary beneath its tortured surface: a global magma ocean. This isn't pure molten rock but rather a mixture of liquid and solid material, a planetary slush that extends deep into the interior.

The evidence comes from an unexpected observation. Io's volcanoes don't appear where tidal heating models predict they should. They're shifted 30 to 60 degrees eastward. A 2015 study in The Astrophysical Journal explained this offset by proposing that viscous friction within a subsurface magma ocean generates additional heat and alters the distribution of volcanic hotspots.

Juno's microwave radiometer data combined with infrared imagery revealed something remarkable: evidence of still-warm magma that hasn't yet solidified below Io's cooled crust. About 10% of Io's surface shows these remnants of slowly cooling lava just beneath the volcanic veneer. The findings suggest a subsurface vast magma chamber system with complex geometry, feeding multiple closely-spaced hot spots simultaneously.

If confirmed, this magma ocean would explain Io's sustained volcanic output over billions of years. It would also provide a compelling analog for understanding other tidally heated worlds.

Paradoxically, the most volcanically active body in the solar system also hosts dramatic mountains. Io has about 115 named mountains averaging 157 kilometers in length and 6,300 meters in height. These aren't volcanic peaks like Earth's stratovolcanoes. They're thrust-fault mountains, created when the weight of volcanic deposits compresses and deforms the lithosphere.

Think of it like this: as volcanic material accumulates on Io's surface, the added weight creates subsidence. The crust responds by cracking and thrusting upward along fault lines. Basal scarps found on all Ionian mountains indicate vigorous crustal deformation driven by rapid resurfacing.

The mountains provide crucial information about Io's lithospheric strength and the depth of tidal heating. If heating occurred only in a shallow asthenosphere, the crust couldn't support such massive structures. The mountains' existence constrains models of Io's internal layering and heat distribution.

Io isn't just a curiosity. It's a laboratory for understanding tidal volcanism throughout the universe. Dozens of exoplanets have been discovered in tight orbits around their parent stars, subjected to tidal forces potentially far stronger than Io experiences. Some of these worlds likely host volcanism that makes Io look calm.

The isotope measurement technique used to determine Io's volcanic history offers a method to detect volcanism on exomoons where direct surface imaging remains impossible. Spectroscopic observations could reveal isotope ratios enriched by billions of years of volcanic outgassing, even from light-years away.

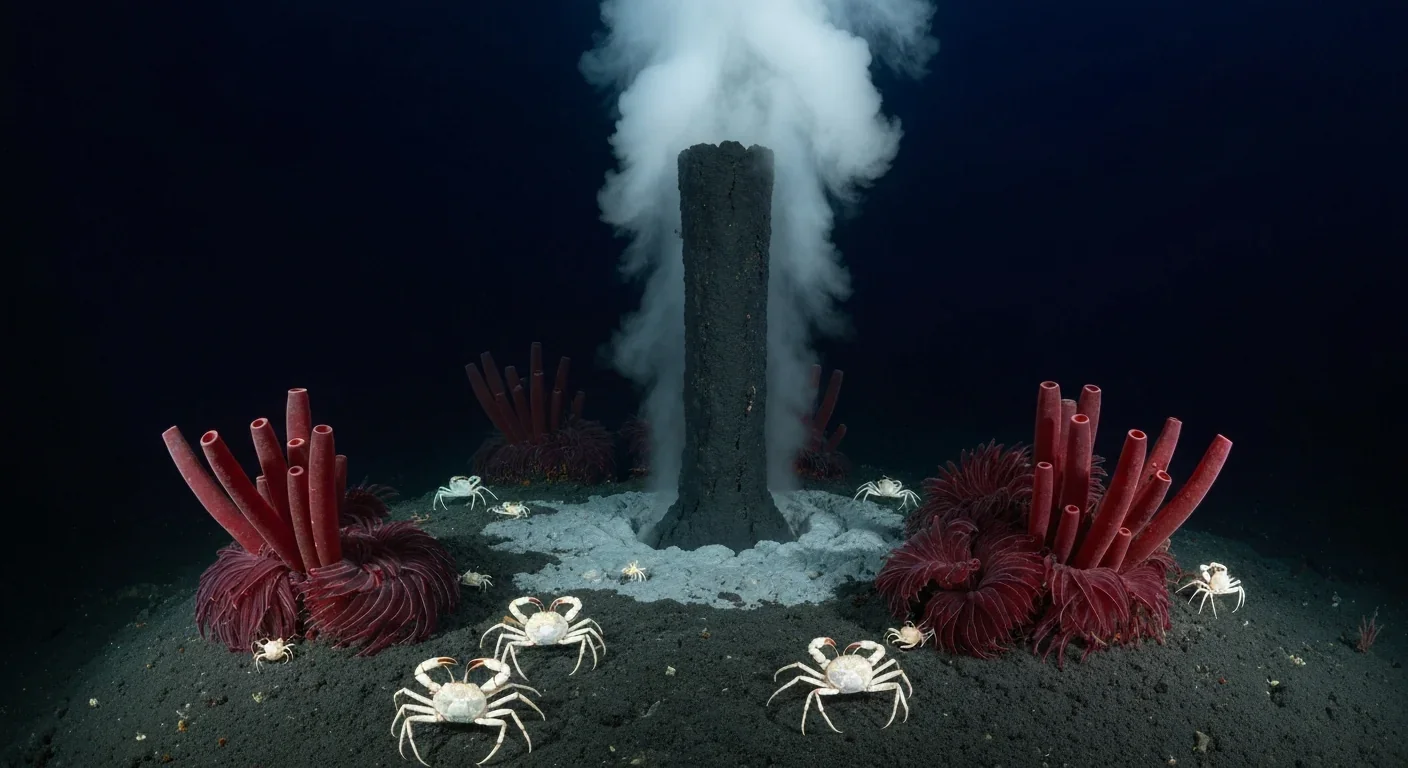

Other moons in our solar system show hints of Io-like processes. Enceladus ejects water-ice plumes from fractures near its south pole, powered at least partially by tidal heating from Saturn. Europa's subsurface ocean likely maintains its liquid state through similar tidal friction. Even Neptune's moon Triton shows evidence of past cryovolcanism.

Understanding Io's extreme volcanism helps scientists model the habitability of ocean worlds. Tidal heating doesn't just power volcanoes - it can maintain liquid water in subsurface oceans for billions of years, independent of a star's warmth. That dramatically expands the potential locations for life in the universe.

"The intriguing feature could improve our understanding of volcanism not only on Io but on other worlds as well."

- Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator

Europe's JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) mission, launched in 2023, will arrive at Jupiter in 2031. While its primary targets are Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa, JUICE will conduct multiple flybys of Io, gathering data on its volcanic activity and internal structure. The mission carries instruments specifically designed to study tidal interactions and heat flow.

JUICE's gravitational measurements during Io encounters will help determine whether a global magma ocean truly exists. Radio science experiments can detect density variations in the interior, distinguishing between solid rock, partial melt, and fully molten regions. The spacecraft's spectrometers will analyze volcanic plume compositions with unprecedented precision.

Future missions might deploy Io-dedicated orbiters capable of sustained observation campaigns. Such missions face extreme challenges - Jupiter's radiation environment remains one of the harshest in the solar system - but the scientific payoff would be enormous. Detailed thermal mapping could reveal the three-dimensional structure of Io's magma plumbing, constraining tidal dissipation models with precision impossible from flyby data alone.

Ground-based observatories continue pushing their capabilities. The James Webb Space Telescope's infrared instruments can detect volcanic hot spots and track eruption cycles. Adaptive optics systems on large ground-based telescopes achieve resolution approaching spacecraft imagery, monitoring Io's volcanic activity continuously.

Io will continue its violent convulsions for as long as the orbital resonance with Europa and Ganymede persists. The system appears stable over timescales of billions of years. That means Io's volcanoes have been erupting since the solar system's formation and will continue erupting until Jupiter's moons eventually spiral inward or the sun expands into a red giant.

Every second, Io generates enough heat to power several large cities. Every year, it resurfaces an area comparable to a large country. Every million years, it renews its entire surface multiple times over. This isn't geology - it's sustained planetary catastrophe.

Yet within that catastrophe lies profound insight. Io demonstrates that small bodies can maintain geological activity through gravitational interactions alone. It proves that volcanism can persist for billions of years without internal radioactive heating. It shows that tidal forces shape planetary evolution as powerfully as stellar radiation or chemical composition.

The 400 volcanoes of Io aren't just features of one peculiar moon. They're windows into fundamental planetary processes, laboratories for extreme chemistry, and harbingers of what we might find on worlds orbiting distant stars. In studying Io's violence, we're learning the rules that govern volcanic worlds throughout the cosmos.

And every time Juno swoops past, the moon surprises us again - reminding us that even in a solar system we've explored for decades, the capacity for discovery remains limitless.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.