Triton: Neptune's Doomed Moon in a Death Spiral

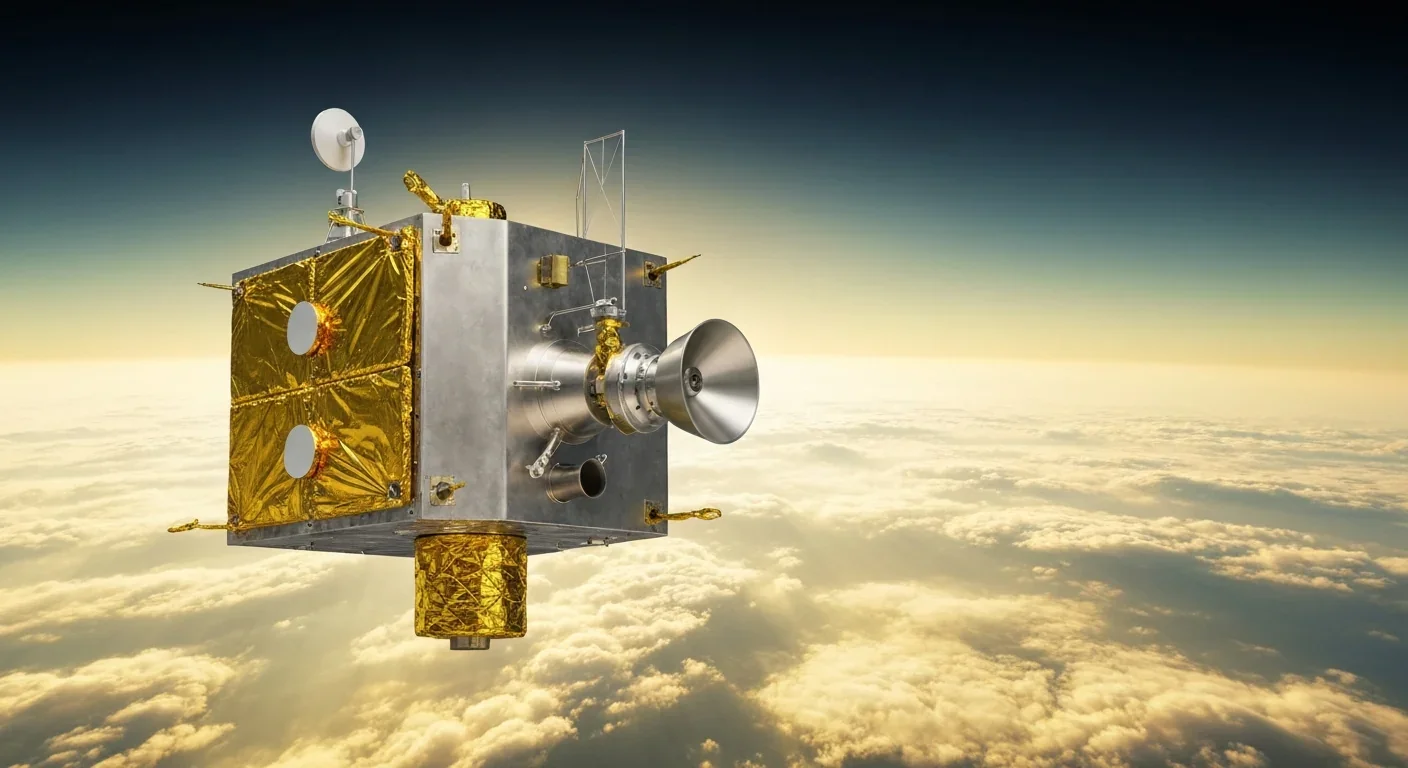

TL;DR: NASA's DAVINCI mission will drop a titanium-shielded probe through Venus's hellish atmosphere in the 2030s, surviving 90 atmospheres of pressure and lead-melting temperatures to study why Earth's twin became uninhabitable - insights that could illuminate climate tipping points and our own planet's future.

By the early 2030s, NASA's DAVINCI mission will attempt something that sounds like science fiction: dropping a probe through Venus's crushing atmosphere to capture data that could rewrite our understanding of planetary evolution, climate change, and possibly even life itself. The challenge? Surviving temperatures that melt lead, pressures 90 times greater than Earth's surface, and clouds of sulfuric acid - all while collecting critical measurements during a precise 17-minute window in the lower atmosphere.

What's happening on Venus isn't just about exploring another planet. It's about understanding why Earth's near-twin became a hellscape while our world flourished with life. The answers could reshape how we think about climate tipping points, planetary habitability, and humanity's long-term survival.

Venus wasn't always hell. Scientists believe that billions of years ago, Venus may have had liquid water oceans and conditions potentially suitable for life. Then something catastrophic happened - a runaway greenhouse effect transformed it into the hottest planet in our solar system, despite being farther from the Sun than Mercury.

"Venus is a 'Rosetta stone' for reading the record books of climate change, the evolution of habitability, and what happens when a planet loses a long period of surface oceans."

- James Garvin, DAVINCI Principal Investigator, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

This isn't abstract science. Venus represents Earth's possible future if we mismanage our own atmospheric chemistry. The planet's atmosphere is now 96.5% carbon dioxide, creating surface temperatures around 460°C (860°F) - hot enough to melt lead, zinc, and tin. Understanding how Venus reached this state could provide crucial insights into Earth's climate system and the boundaries of planetary habitability.

Creating hardware that can function on Venus requires solving problems that push the boundaries of materials science and engineering. The DAVINCI probe must withstand conditions that would instantly destroy conventional spacecraft.

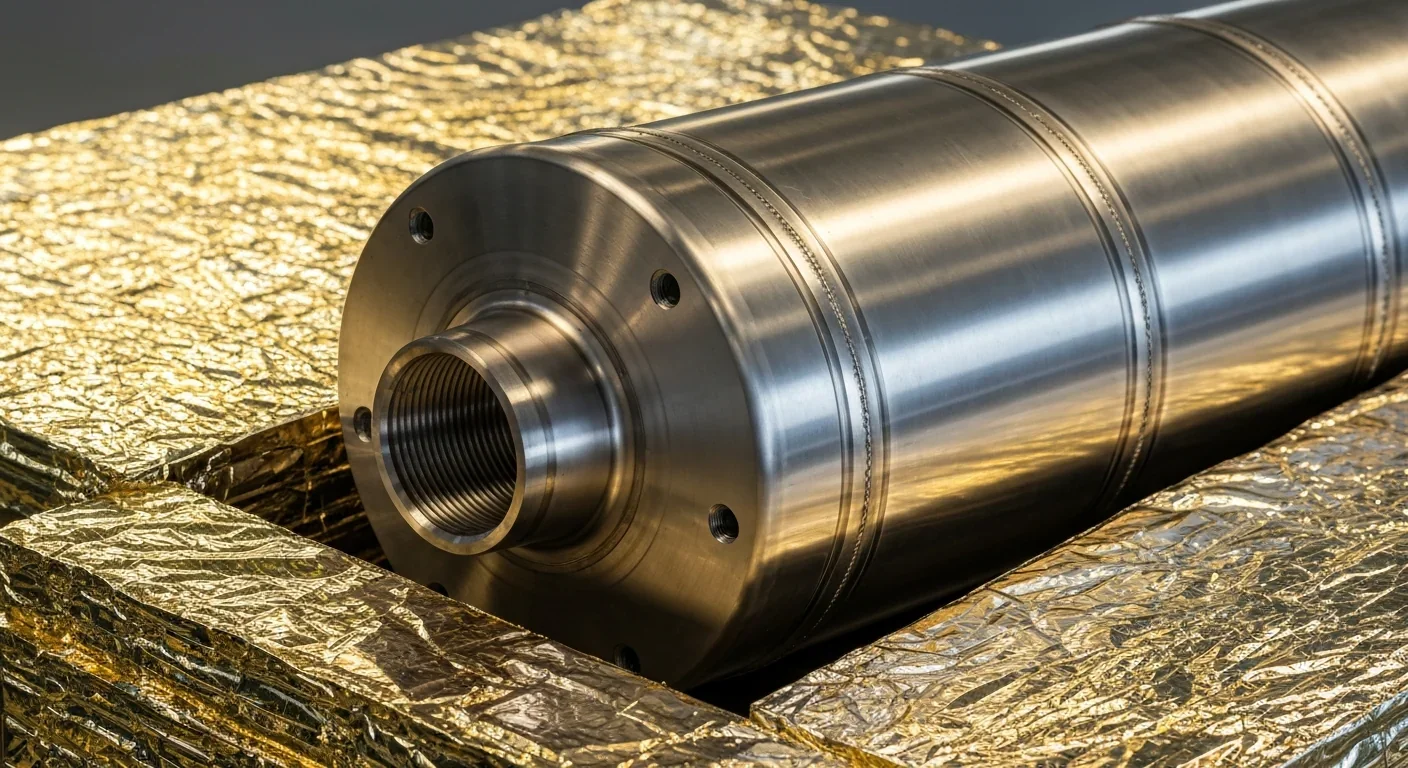

The probe's core protection comes from a titanium pressure vessel engineered to maintain structural integrity under 90-100 atmospheres of pressure. To put that in perspective, it's like being crushed under the weight of a kilometer of ocean water.

Titanium was chosen because it combines exceptional strength-to-weight ratio with remarkable corrosion resistance. The vessel must not only withstand immense pressure but also resist the corrosive sulfuric acid that permeates Venus's atmosphere. Previous Soviet Venera missions demonstrated that ordinary materials quickly fail in these conditions - some probes lasted mere minutes on the surface.

Temperature control presents an even more complex challenge. The probe uses a sophisticated multi-layered thermal protection system combining a ceramic heat shield with advanced insulation materials.

The outer heat shield, jettisoned at approximately 67 kilometers altitude, protects during the initial descent through the upper atmosphere. Once released, the probe relies on high-temperature multi-layer insulation - layers of advanced ceramic and silica fabrics separated by reflective aluminum sheets that create thermal barriers while remaining lightweight.

Inside the titanium vessel, instruments are further protected by specialized high-temperature electronics. Silicon carbide semiconductors, which can operate at temperatures exceeding 500°C, likely play a crucial role. These components represent a breakthrough from conventional silicon-based electronics, which fail around 150°C.

Modern materials science has enabled electronics that function at temperatures that would melt conventional computer chips. Silicon carbide semiconductors can operate above 500°C - more than three times hotter than traditional silicon can withstand.

Even the parachute requires innovation. Most Earth-friendly parachute materials, like nylon, would dissolve in Venus's sulfuric acid clouds. DAVINCI will use a material that's resistant to acids and five times stronger than steel, ensuring the probe can slow its descent without the parachute disintegrating.

The parachute works in concert with Venus's incredibly dense atmosphere - about 50 times thicker than Earth's at sea level - which provides natural drag to slow the probe's fall. This combination allows for a controlled descent that gives instruments time to gather data.

DAVINCI carries five scientific instruments specifically designed to answer fundamental questions about Venus's atmosphere, history, and potential for harboring life.

The VMS will measure the composition of the atmosphere with unprecedented precision, focusing on noble gases, trace chemicals, and isotope ratios. These measurements act like a time machine - isotope ratios of hydrogen, for instance, can reveal how much water Venus once had and when it was lost.

By comparing Venus's noble gas abundances with Earth and Mars, scientists can reconstruct the divergent evolutionary paths of terrestrial planets. Did Venus lose its water gradually or catastrophically? The answer lies in the data VMS will collect.

The VTLS uses laser technology to detect and measure trace gases in Venus's atmosphere, including potential biosignatures. Recent discoveries of phosphine in Venus's clouds sparked debates about whether microbial life could exist in the relatively temperate cloud layers around 50-60 kilometers altitude, where temperatures and pressures are remarkably Earth-like.

While phosphine detection remains controversial, the VTLS will provide definitive measurements of atmospheric chemistry that could settle the question or reveal other unexpected compounds.

VASI monitors temperature, pressure, and wind during descent, creating a detailed vertical profile of the atmosphere. This data helps scientists understand atmospheric dynamics, including how Venus's super-rotating winds - which circle the planet in just four Earth days despite the planet's 243-day rotation - maintain their incredible speeds.

VenDI will capture the first close-up images of Venus's surface in over four decades. The Soviet Venera missions returned a handful of surface photographs before succumbing to the heat, but VenDI promises far higher resolution.

The target landing zone, Alpha Regio, is one of Venus's highland regions - ancient terrain that may contain rocks formed by water. If VenDI identifies geological features suggesting past water activity, it would provide visual confirmation of Venus's potentially habitable past.

Continuous monitoring throughout descent provides crucial data about how Venus's atmosphere behaves from the cold upper regions through the scorching lower atmosphere. These measurements help validate atmospheric models and improve predictions about Venus's weather patterns.

DAVINCI's journey to Venus involves careful choreography designed to maximize scientific return while conserving resources.

The mission will use three Venus gravity assists to fine-tune its trajectory and conserve fuel. The first two assists set up the carrier spacecraft (called CRIS - Carrier, Relay, and Imaging Spacecraft) for Venus flybys to perform remote sensing observations. The third assist positions CRIS to release the descent probe at the optimal entry point.

This approach demonstrates how modern interplanetary missions economize resources. Instead of using massive amounts of fuel for trajectory corrections, mission planners leverage planetary gravity to "slingshot" spacecraft into precise positions.

Released at approximately 120 kilometers altitude, the probe begins its hour-long plunge through Venus's atmosphere. The journey happens in distinct phases:

Upper atmosphere (120-67 km): The heat shield protects against aerodynamic heating as the probe slams into increasingly dense air. Deceleration forces build as atmospheric density increases.

Heat shield jettison (67 km): With the intense heating phase complete, the probe sheds its heat shield to reduce weight and expose scientific instruments. The parachute deploys to further slow descent.

Science operations (67 km to surface): For approximately one hour, all five instruments collect data continuously. The VenDI begins capturing images once the probe drops below the cloud deck, providing increasingly detailed views of Alpha Regio.

Critical lower atmosphere window (final 17 minutes): This is the mission's most crucial phase. As the probe descends below 10 kilometers altitude, it enters the hottest, most pressurized region - the conditions most likely to stress the spacecraft to its limits. Yet this is also where the most interesting chemistry may occur, including potential cloud-layer biosignatures.

"If we survive the touchdown at about 25 miles per hour, we could have up to 17-18 minutes of operations on the surface under ideal conditions."

- Stephanie Getty, Deputy Principal Investigator, DAVINCI

DAVINCI is designed to collect all required science data before reaching the surface. However, if the probe survives touchdown - expected at about 25 miles per hour - it could have an additional 17-18 minutes of surface operations under ideal conditions.

Those minutes would be precious. Surface measurements could detect seismic activity, analyze surface composition directly, and provide ground truth for orbital observations. But mission success doesn't depend on surviving landing - the atmospheric data alone justifies the entire mission.

Throughout descent, the probe transmits data to the CRIS orbiter overhead, which relays information to Earth in near real-time. This approach ensures that even if the probe fails during descent, scientists receive the data collected up to that point.

The relay system must function through Venus's incredibly dense atmosphere, a communications challenge that required careful antenna design and signal processing algorithms.

DAVINCI builds on decades of Venus exploration, particularly the remarkable achievements of the Soviet Venera program. Between 1961 and 1984, the Soviet Union launched numerous missions to Venus, gradually learning to survive the hostile conditions.

Early attempts failed spectacularly. Venera 4 in 1967 was crushed by atmospheric pressure before reaching the surface - Soviet engineers had underestimated Venus's atmospheric density by a factor of ten. Subsequent missions strengthened their pressure vessels and improved heat shielding.

Venera 8 successfully transmitted from the surface for 50 minutes in 1972, measuring temperature, pressure, and light levels. Venera 9 and 10 returned the first images from another planet's surface in 1975 - grainy black-and-white photographs showing a landscape of flat rocks under diffuse lighting.

Venera 13 and 14, launched in 1981, represented the program's pinnacle. Venera 13 survived on the surface for 127 minutes - still the record for any Venus lander - and returned the first color images from Venus's surface, showing an orange-tinted landscape under thick clouds.

The Soviet Venera 13 probe holds the record for longest survival on Venus's surface: 127 minutes. Modern materials and electronics may extend future missions to hours or even days.

These Soviet achievements proved that surviving Venus's surface is possible with proper engineering. DAVINCI applies 21st-century materials science, electronics, and manufacturing techniques to these hard-won lessons, aiming not just to survive but to conduct sophisticated scientific measurements throughout descent.

DAVINCI is part of a broader Venus exploration renaissance. After decades of neglect - NASA's last Venus probe mission was Pioneer Venus in 1978 - multiple space agencies are now planning Venus missions for the 2030s.

NASA selected DAVINCI alongside VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy), which will use radar to map Venus's surface in unprecedented detail. The European Space Agency's EnVision mission, also targeting the early 2030s, will study Venus's geological activity and search for volcanic hotspots.

Russia's Roscosmos has proposed Venera-D, potentially launching by 2036, which would include both an orbiter and a long-duration surface station. Meanwhile, private companies and smaller space agencies are exploring low-cost Venus missions using cubesats and balloon probes.

This renewed interest stems from several factors. First, improved technology makes Venus missions more feasible and less expensive than in previous decades. Second, the potential discovery of biosignatures in Venus's clouds has energized the astrobiology community. Third, Venus's relevance to understanding Earth's climate has become increasingly apparent as we grapple with our own greenhouse gas emissions.

The scientific questions DAVINCI will address have profound implications far beyond planetary science.

By determining when and how Venus lost its water, DAVINCI can illuminate the conditions that trigger irreversible climate change. Did Venus's transformation happen gradually over billions of years, or was there a sudden tipping point beyond which feedback mechanisms spiraled out of control?

These insights matter for Earth. While our planet's climate differs significantly from ancient Venus, understanding the physical principles governing planetary climate systems helps us identify warning signs and predict long-term outcomes of atmospheric changes.

If Venus once had oceans, it may have been habitable for life. DAVINCI's measurements of noble gases and isotope ratios will reveal how long water persisted and whether conditions could have supported biological processes.

This research directly informs the search for habitable exoplanets. Thousands of "Venus-like" worlds have been discovered orbiting other stars. Understanding Venus's atmospheric chemistry helps astronomers distinguish potentially habitable worlds from hellish ones in distant solar systems.

The most speculative but tantalizing possibility is that Venus's clouds might harbor microbial life. At 50-60 kilometers altitude, Venus's atmosphere features temperatures around 20-30°C and roughly Earth-like pressure - far more benign than the surface below or the frozen void above.

Some Earth microbes survive in similarly extreme environments - acidic hot springs, high-altitude clouds, and deep-ocean hydrothermal vents. Could analogous organisms drift in Venus's clouds, metabolizing sulfur compounds and reproducing in sulfuric acid droplets?

DAVINCI's instruments will search for chemical signatures inconsistent with known abiotic processes. While finding definitive proof of life requires sample return missions, DAVINCI could provide compelling evidence that warrants follow-up investigation.

VenDI's images of Alpha Regio could reveal whether Venus remains geologically active. Recent observations suggest possible volcanic activity, but confirmation requires surface observations. If DAVINCI spots fresh lava flows or thermal anomalies, it would indicate Venus has a dynamic interior like Earth, rather than being a geologically dead world.

This matters because geological activity helps maintain habitability - Earth's plate tectonics recycle atmospheric carbon and prevent runaway greenhouse effects. If Venus was ever geologically active, understanding when and why that activity ceased provides clues about long-term planetary evolution.

DAVINCI represents just the beginning of systematic Venus exploration. Future missions will build on its discoveries with longer-duration surface stations, atmospheric balloons, and eventually sample return missions.

Engineers are developing high-temperature electronics that could enable surface missions lasting days or weeks rather than minutes. Silicon carbide and gallium nitride semiconductors can operate at temperatures exceeding 500°C, potentially eliminating the need for elaborate cooling systems.

Some visionaries propose Venus cloud cities - habitable stations floating in the temperate cloud layers where conditions are remarkably Earth-like. At 50 kilometers altitude, humans would need acid-resistant suits but not pressure suits - the atmospheric pressure is similar to sea level on Earth. Solar panels would work efficiently above the clouds, and the atmosphere itself provides shielding from cosmic radiation.

Even terraforming Venus has been seriously studied. While it would take centuries or millennia, proposed methods include solar shades to cool the planet, atmospheric processors to remove carbon dioxide, and importing hydrogen to create water. Whether such projects are feasible or desirable remains hotly debated, but they illustrate Venus's potential as a second home for humanity.

At 50 kilometers altitude in Venus's atmosphere, conditions are surprisingly Earth-like: temperatures around 20-30°C and roughly sea-level pressure. This has led scientists to propose floating research stations or even permanent habitats in Venus's clouds.

DAVINCI's mission transcends pure science - it connects to fundamental questions about humanity's place in the cosmos and our responsibility as planetary stewards.

Venus demonstrates that planets can undergo catastrophic environmental change. While the mechanisms differ from human-caused climate change on Earth, the lesson is clear: planetary atmospheres are not static or infinitely resilient. They can reach tipping points beyond which recovery becomes impossible.

This knowledge should inform how we approach Earth's climate crisis. Venus isn't a prediction of Earth's future - our planet's distance from the Sun and different atmospheric composition provide significant buffers. But Venus serves as a warning about what happens when greenhouse gas concentrations spiral out of control.

The mission also exemplifies international scientific collaboration. While NASA leads DAVINCI, the mission includes contributions from European, Japanese, and other international partners. Venus exploration more broadly involves agencies from multiple nations working toward common scientific goals - a model for how humanity can address shared challenges.

For the next generation of scientists and engineers, DAVINCI provides inspiration. The mission pushes technological boundaries, requires creative problem-solving, and aims to answer profound questions about planetary evolution and the potential for life beyond Earth. Young people today will build the future Venus exploration missions that follow DAVINCI's pathfinding journey.

As DAVINCI prepares for launch in the early 2030s, excitement builds across the planetary science community. The mission promises to rewrite textbooks, resolve long-standing debates, and pose new questions that will drive exploration for decades to come.

The data DAVINCI collects during its hour-long descent - particularly those critical 17 minutes in the lower atmosphere - will provide our most detailed look yet at Venus's hostile environment. Each measurement brings us closer to understanding why Earth's twin became a cautionary tale rather than a second haven for life.

In surviving Venus's inferno, DAVINCI does more than gather scientific data. It demonstrates human ingenuity, our capacity to build machines that function in environments no human could survive, and our relentless curiosity about the cosmos. The probe's titanium hull will crush under immense pressure, its electronics will fail in the searing heat, and its mission will end on Venus's scorching surface.

But the knowledge gained will endure, reshaping how we understand planetary evolution, climate change, and the delicate balance of conditions that makes Earth habitable. In studying Venus's hellish present, we glimpse our planet's precious past and potentially fragile future - lessons written in the crushing atmosphere of our nearest neighbor.

Triton, Neptune's largest moon, orbits backward at 4.39 km/s. Captured from the Kuiper Belt, tidal forces now pull it toward destruction in 3.6 billion years.

Banned pesticides like DDT persist in food chains for decades, concentrating in fatty fish and dairy products, then accumulating in human tissues where they disrupt hormones and increase health risks.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

Humans systematically overestimate how single factors affect future happiness while ignoring broader context - a bias called the focusing illusion. This cognitive flaw drives poor decisions about careers, purchases, and relationships, and marketers exploit it ruthlessly. Understanding this bias and adopting systems-based thinking can improve decision-making, though awareness alone doesn't eliminate the effect.

Scientists have discovered lichens living inside Antarctic rocks that survive extreme cold, radiation, and desiccation - conditions remarkably similar to Mars. These cryptoendolithic organisms grow just micrometers per year, can live for thousands of years, and have remained metabolically active in Martian simulations, offering profound insights into life's limits and the potential for extraterrestrial biology.

The nonprofit sector has grown into a $3.7 trillion industry that may perpetuate the very problems it claims to solve by professionalizing poverty management and replacing systemic reform with temporary relief.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.