Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: NASA's Lunar Gateway, launching December 2027, will be humanity's first space station in lunar orbit - a critical staging point for Artemis missions returning astronauts to the Moon by 2026 and enabling sustained deep space exploration toward Mars.

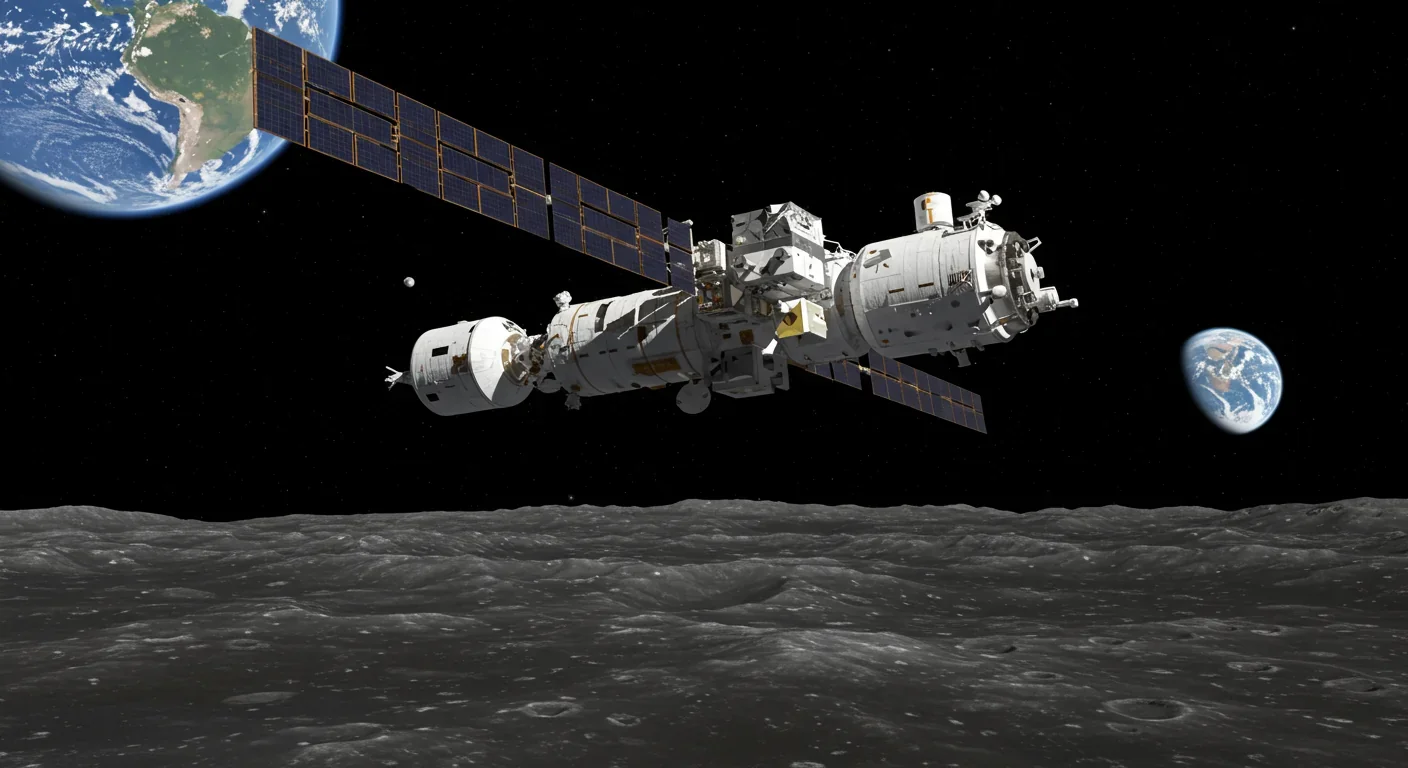

Within the next two years, a new frontier in human space exploration will open above the Moon's cratered surface. Not on it - above it. The Lunar Gateway represents humanity's first attempt to build permanent infrastructure in cislunar space, a radical departure from every space station we've constructed before. Unlike the International Space Station, which orbits a predictable path 250 miles above Earth, Gateway will swing through a tilting, elliptical orbit around the Moon, sometimes coming within 1,000 miles of the lunar surface before soaring out to 43,500 miles away. This isn't just another space station. It's the staging ground for Artemis III, the mission that will put boots back on lunar soil for the first time since 1972.

The International Space Station taught us how to live in orbit. Gateway will teach us how to thrive beyond Earth's protective embrace. The Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit (NRHO) that Gateway will occupy isn't a circular path like the ISS follows - it's a gravitationally balanced sweet spot where the combined pull of Earth and Moon creates a stable parking spot that requires minimal fuel to maintain.

This orbit delivers three strategic advantages. First, Gateway enjoys near-continuous communication with both Earth and the lunar surface, eliminating the radio blackouts that plagued Apollo missions. Second, the station receives nearly constant sunlight on its massive solar arrays, solving the power problems that plague satellites in lunar orbit. Third, spacecraft can reach Gateway from Earth or the lunar surface with far less fuel than conventional orbits require.

But here's the revolutionary part: Gateway won't be permanently occupied. While the ISS has hosted rotating crews continuously since 2000, Gateway will support astronauts only during active mission periods. Between crew visits, the station operates autonomously, conducting science experiments and serving as a parking garage for spacecraft. This intermittent occupation model reduces costs, extends the station's 15-year design life, and allows mission planners to concentrate resources during critical landing windows.

NASA's decision to build Gateway initially drew skepticism. Critics argued that a lunar space station added unnecessary complexity and expense to missions that could go directly to the lunar surface. Some proposals suggested eliminating Gateway entirely, sending astronauts straight from Earth to Moon like Apollo did. But that criticism misses the long game NASA is playing.

Gateway's intermittent occupation model represents a fundamental shift in how we think about space stations - between crew visits, the station operates autonomously as both laboratory and logistics hub, reducing costs while extending operational lifetime.

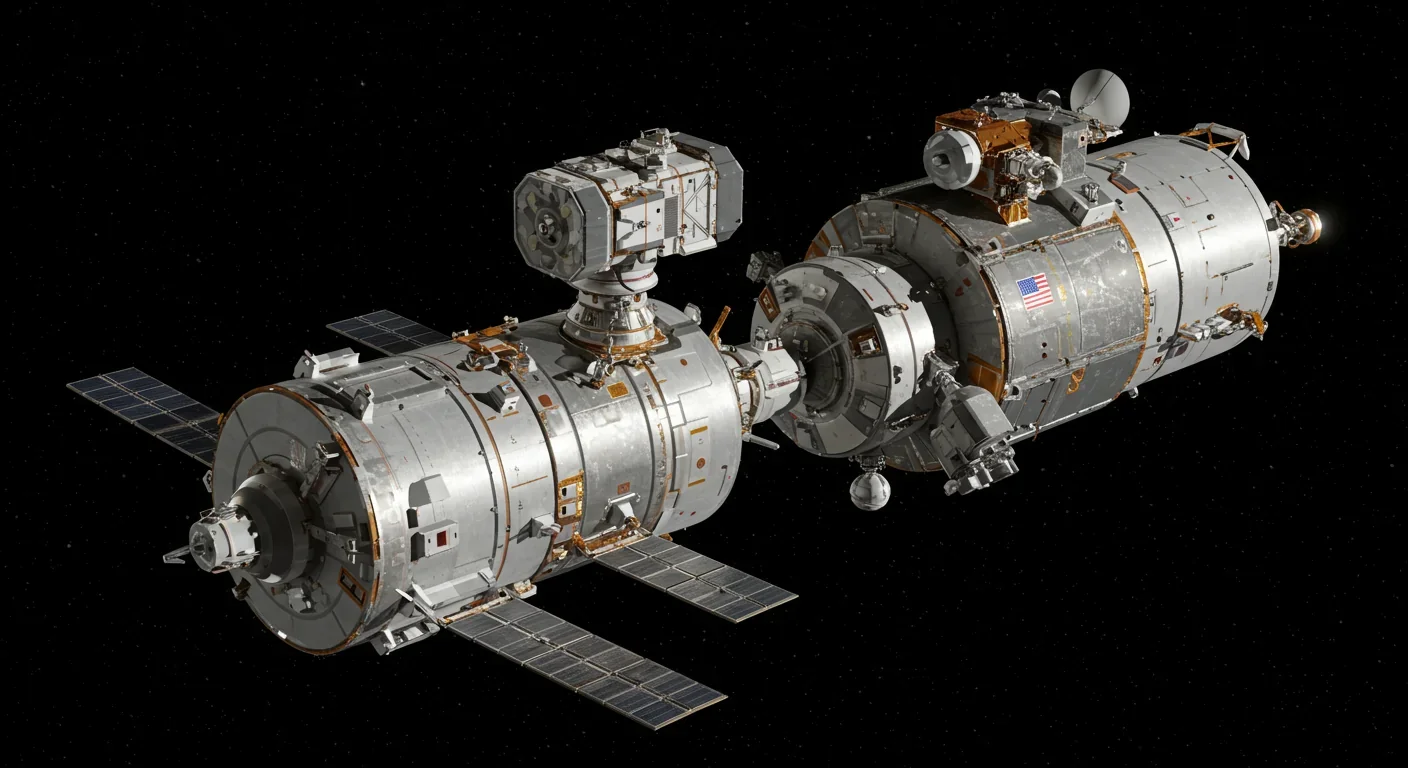

Gateway's modular design reflects lessons learned from three decades of ISS operations. Rather than launching a completed station, NASA will assemble Gateway piece by piece in lunar orbit, starting with two fundamental components.

The Power and Propulsion Element (PPE), built by Maxar Technologies, serves as Gateway's backbone. This 60-kilowatt solar electric propulsion spacecraft generates more power than many terrestrial neighborhoods while maintaining the station's orbit and orientation. The PPE's electric thrusters, fueled by xenon gas, provide the gentle, continuous thrust needed to counteract gravitational perturbations. But the PPE isn't just a tugboat - it's a communications relay station with high-speed data links to Earth, capable of beaming science data and 4K video from lunar orbit.

Attached to the PPE from day one will be HALO (Habitation and Logistics Outpost), the module where astronauts will live and work during their lunar missions. HALO's design borrows heavily from Northrop Grumman's Cygnus cargo spacecraft, which has been reliably delivering supplies to the ISS since 2013. That proven heritage matters in deep space, where repair missions are impossible and failure means losing years of work.

HALO arrived in the United States in late 2024 after completing construction and testing at Thales Alenia Space's facility in Turin, Italy. The module passed rigorous pressure tests and structural stress evaluations, proving it can withstand the thermal extremes and radiation exposure of cislunar space. Inside HALO's pressurized volume, astronauts will find command and control stations, life support systems, sleeping quarters, and storage for months of supplies.

The integrated PPE-HALO stack is scheduled to launch no later than December 2027 aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket. After launch, the combined modules will spend approximately one year transiting to their NRHO destination - a journey that doubles as a science mission, with radiation sensors collecting data on the deep space environment that future Mars crews will experience.

Gateway represents the most ambitious international space collaboration since the ISS. While NASA leads the program, the European Space Agency (ESA), Canadian Space Agency (CSA), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and the United Arab Emirates' Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) are all contributing critical hardware.

ESA is developing the Lunar I-Hab, Gateway's second habitation module, which will arrive during the Artemis IV mission. This European-built module adds laboratory space, crew quarters, and environmental control systems. ESA is also providing the Lunar Link, a high-speed communication system that will enable video calls between Gateway crews and mission control, plus data relay for lunar surface rovers and experiments.

Canada's contribution might sound familiar: Canadarm3, the next generation of the robotic arm that became iconic on the Space Shuttle and ISS. But Canadarm3 represents a quantum leap in capability. This intelligent robotic system can operate autonomously, performing maintenance tasks, capturing visiting spacecraft, and moving equipment without constant human supervision. In an environment where every astronaut hour is precious, an autonomous robotic assistant multiplies crew productivity.

JAXA is designing critical life support systems for the Lunar I-Hab, including batteries, environmental controls, and the HTV-XG cargo vehicle that will ferry supplies to Gateway. These contributions leverage Japan's extensive experience with the HTV cargo vehicles that serviced the ISS for years.

The MBRSC's participation represents Gateway's newest international dimension. The UAE is developing the Gateway Crew and Science Airlock, scheduled for delivery on Artemis VI. This module will allow astronauts to conduct spacewalks and expose experiments to the lunar space environment without depressurizing the entire station.

"Building and testing hardware for Gateway is truly an international collaboration. We're seeing teams from multiple nations working together to create something unprecedented in human history."

- Jon Olansen, Gateway Program Manager at NASA's Johnson Space Center

These international partnerships distribute costs, leverage global expertise, and build the diplomatic foundation for sustained deep space exploration. When a dozen nations have invested billions in lunar infrastructure, the political momentum for sustaining the program becomes formidable.

Understanding Gateway's role requires understanding how radically different Artemis missions are from Apollo. During the Apollo program, astronauts launched from Earth, flew directly to lunar orbit, landed on the Moon for a few days, then returned directly to Earth. The entire architecture was disposable - everything except the tiny command module burned up or was abandoned.

Artemis missions work differently. Astronauts will launch from Earth aboard NASA's Orion spacecraft, which delivers crews to Gateway. The Orion capsule docks with Gateway, where crews transfer to a waiting lunar lander for descent to the surface. After completing their surface mission - potentially lasting weeks rather than days - astronauts return to Gateway, transfer back to Orion, and ride home to Earth.

This choreography makes Gateway indispensable. The lunar landers being developed by SpaceX and Blue Origin are too large to fit inside a single launch vehicle with Orion. They must launch separately, rendezvous with Gateway, and wait for crews to arrive. Gateway serves as the parking lot, the gas station, the hotel, and the transfer point that makes reusable lunar infrastructure possible.

For Artemis III, currently targeting 2026, SpaceX's Starship Human Landing System will be pre-positioned at Gateway. When the Artemis III crew arrives aboard Orion, they'll dock with Gateway, transfer to Starship, and descend to the lunar South Pole region. After their surface mission, they'll return to Gateway, re-board Orion, and head home. Starship remains at Gateway for refueling and reuse on subsequent missions.

Artemis IV, the first crewed mission to Gateway itself, will deliver the Lunar I-Hab module. This mission demonstrates another crucial capability: on-orbit assembly by astronaut crews. Unlike the ISS, which required dozens of spacewalks to connect modules, Gateway's standardized docking interfaces allow robotic and crew-assisted assembly with minimal EVA time.

By Artemis V, Gateway will mature into a true lunar outpost, with Blue Origin's Blue Moon lander joining SpaceX's system to provide redundancy and increased landing capacity. Multiple landers enable overlapping missions, surface base construction, and the scientific infrastructure needed for sustained exploration.

While Gateway's primary role supports Artemis landings, the station's scientific capabilities justify its existence even if surface missions were delayed. Gateway occupies a unique location for observing cosmic phenomena, conducting life sciences research, and testing technologies for Mars missions.

Three radiation-focused science payloads will launch with the initial PPE-HALO stack, measuring solar particle events and cosmic rays that bombard spacecraft beyond Earth's magnetic field. These measurements are critical for designing countermeasures that will protect crews during multi-year Mars expeditions. Gateway's crew will experience radiation exposures similar to what Mars voyagers will face, making them pioneers in testing protective strategies.

Gateway's observation platform provides unobstructed views of Earth, the Moon, and deep space. Astrophysics instruments mounted on Gateway's exterior will observe the universe without atmospheric interference or orbital limitations that constrain Earth-based or ISS-mounted telescopes. Lunar science experiments will monitor the Moon's exosphere, magnetic anomalies, and surface composition with instruments far more capable than those Apollo astronauts could deploy.

Life sciences research at Gateway investigates how humans adapt to deep space environments. The radiation exposure, communication delays, and psychological isolation that Gateway crews experience mirror challenges Mars explorers will face. Medical experiments will test countermeasures for bone loss, muscle atrophy, cardiovascular changes, and immune system dysfunction caused by long-duration spaceflight.

Gateway's unique position beyond Earth's protective magnetic field makes it the perfect laboratory for testing Mars mission technologies and medical countermeasures - if a system fails at Gateway, crews can return to Earth within days rather than being stranded millions of miles away.

Technology demonstration is Gateway's third scientific role. Advanced life support systems, closed-loop recycling, and autonomous operations tested at Gateway reduce risks for Mars missions. If a system fails at Gateway, the crew can return to Earth within days. If the same system fails en route to Mars, the mission ends in tragedy. Gateway serves as the proving ground where we learn to survive far from Earth.

Gateway isn't just a government project - it's catalyzing commercial activity in cislunar space. SpaceX's Falcon Heavy launches Gateway's first modules, but the company's involvement extends far beyond transportation. SpaceX is developing both the Starship Human Landing System and logistics spacecraft for transferring crew and cargo between Gateway and the lunar surface.

Blue Origin won contracts to develop the Blue Moon lunar lander for Artemis V and cargo delivery spacecraft for subsequent missions. This competition between SpaceX and Blue Origin mirrors the Commercial Cargo and Commercial Crew programs that transformed access to the ISS, driving down costs while improving reliability.

Maxar Technologies, a company specializing in satellite manufacturing, is building Gateway's Power and Propulsion Element. Northrop Grumman, which developed the Cygnus cargo vehicle for ISS resupply, adapted that design to create HALO. Thales Alenia Space, an Italian aerospace manufacturer, fabricated HALO's pressure vessel. These partnerships demonstrate how commercial capabilities developed for Earth orbit can extend to deep space applications.

The commercial sector sees Gateway as an anchor customer that justifies investing in cislunar capabilities. Companies are developing lunar rovers, surface habitats, mining equipment, and communication networks that depend on Gateway as a logistics hub. Just as the ISS stimulated commercial space stations and orbital manufacturing, Gateway may catalyze a cislunar economy where government and private activities reinforce each other.

Building and operating Gateway requires solving problems that have never been addressed before. The NRHO orbit, while advantageous for communications and fuel efficiency, presents navigation challenges that don't exist in circular orbits. Gateway's distance from Earth varies dramatically throughout each orbit, affecting communication delays, thermal conditions, and rendezvous planning.

Radiation protection is a more severe challenge at Gateway than aboard the ISS. Earth's magnetic field shields the ISS from most cosmic rays and solar particle events. Gateway enjoys no such protection. Advanced modeling is helping engineers design shielding that balances radiation protection against mass constraints, but crew exposure limits will restrict mission durations until better countermeasures are developed.

Micrometeoroid impacts pose heightened risks in cislunar space, where debris detection networks that protect the ISS don't exist. Gateway's modules must withstand particle impacts without immediate repair capabilities. Engineers are designing multi-layer shields and damage-tolerant structures, but every impact carries risk.

Lunar dust, ejected from the Moon's surface by micrometeorite impacts, creates a persistent contamination hazard. This fine, abrasive dust can damage solar panels, optical sensors, and mechanical systems. Gateway's designers are incorporating dust defense strategies including protective covers, electrostatic repulsion, and contamination monitoring.

Life support systems must operate reliably with limited resupply opportunities. While ISS receives cargo deliveries every few months, Gateway resupply missions will be less frequent and more expensive. Closed-loop recycling systems that recover water from humidity and waste are critical. JAXA's life support contributions leverage lessons learned from Japan's Kibo module on the ISS, but scaling these systems for lunar orbit introduces new variables.

Gateway's most vocal critics argue it represents unnecessary complexity driven by political compromises rather than engineering logic. The Artemis architecture requires astronauts to transfer between Orion and a lunar lander at Gateway - a rendezvous that introduces failure modes and delays. Critics propose eliminating Gateway, arguing that lunar landers could meet Orion in low Earth orbit or that direct ascent missions like Apollo's are more efficient.

Budget constraints add weight to these arguments. Gateway's development costs exceed $5 billion, funds that could alternatively accelerate lunar lander development, surface habitat construction, or Mars mission planning. Every dollar spent on Gateway is a dollar not spent on other exploration priorities.

Political vulnerability threatens Gateway's future. The program survived proposed cancellations in the 2025 White House budget, where officials suggested eliminating Gateway to redirect funds toward Mars missions. These proposals reflect genuine debate about whether cislunar infrastructure justifies its costs or whether NASA should focus resources on destinations rather than waypoints.

NASA's response emphasizes Gateway's long-term strategic value. While Gateway adds complexity to initial Artemis missions, it enables sustained lunar exploration that direct flights can't support. Reusable landers need a place to park and refuel. Research programs need a stable platform. International partners need shared infrastructure where their contributions integrate with NASA's systems.

"Gateway, like the ISS before it, will prove its value over decades rather than individual missions. The ISS seemed expensive during construction but is now recognized as humanity's continuous foothold in space."

- NASA Strategic Planning Document

The agency argues that Gateway, like the ISS before it, will prove its value over decades rather than individual missions. The ISS seemed like an expensive distraction when construction began in the 1990s. Today, it's recognized as humanity's continuous foothold in space, where medical discoveries, materials research, and operational lessons justified every dollar invested. Gateway may follow a similar trajectory, maligned during construction but celebrated when sustained lunar presence becomes routine.

Gateway's evolution doesn't end when the initial modules are assembled. NASA has outlined an expansion roadmap that will grow the station's capabilities throughout the 2030s. Beyond the core modules - PPE, HALO, Lunar I-Hab, and the UAE Airlock - additional elements may include an enhanced power module, expanded logistics capability, and specialized science laboratories.

Gateway could become the assembly point for Mars mission elements too large or complex to launch from Earth's surface. Deep space transfer vehicles, propellant depots, and Mars landers might be staged at Gateway before beginning their interplanetary journey. The station's location beyond Earth's gravity well reduces the energy required to reach Mars, making Gateway a logical jumping-off point for missions to the Red Planet.

Commercial modules may eventually attach to Gateway, much as commercial spacecraft now visit the ISS. Private companies are developing inflatable habitats, zero-gravity manufacturing facilities, and propellant production systems that could augment Gateway's capabilities while creating business opportunities in cislunar space.

Gateway's robotic systems could support construction of larger structures in lunar orbit. Solar power satellites, communication arrays, or fuel depots assembled at Gateway would leverage the station's power, communications, and crew support without requiring dedicated infrastructure for each project.

The ultimate vision sees Gateway as the first node in a cislunar transportation network. Additional stations at different lunar orbits, surface bases at multiple landing sites, and Earth-orbit facilities could form an integrated system where spacecraft move routinely between nodes. Gateway wouldn't be an isolated outpost but the anchor point for a web of human activity across the Earth-Moon system.

The Gateway program is creating demand for specialized expertise that didn't exist when ISS construction began. Astronauts training for Gateway missions need skills in long-duration deep space operations, lunar landing support, and autonomous system management. Future Gateway crews will spend less time conducting hands-on experiments and more time managing robotic systems, supporting surface missions, and troubleshooting equipment failures far from ground support.

Engineers working on Gateway systems need expertise in radiation-hardened electronics, autonomous operations, and fault-tolerant design. The forgiving environment of low Earth orbit, where repair missions can launch within weeks and communication is instantaneous, doesn't exist in cislunar space. Gateway engineers must design systems that self-diagnose problems, implement workarounds, and operate for years between servicing opportunities.

Mission planners face trajectory optimization problems that are fundamentally different from LEO operations. Gateway's elliptical NRHO introduces launch windows, rendezvous opportunities, and abort scenarios that require new analytical tools and operational procedures. The skills developed for Apollo missions provide a foundation, but modern computational capabilities and reusable architecture create possibilities that Apollo planners never considered.

As the December 2027 target approaches, final preparations for the PPE-HALO launch are accelerating. SpaceX's Falcon Heavy, which will carry Gateway's first modules to orbit, has proven itself on numerous flights, including launching NASA's Psyche asteroid mission and deploying national security satellites. The rocket's three-core configuration generates 5 million pounds of thrust, enough to send the 40-ton integrated PPE-HALO stack on its year-long journey to NRHO.

Launch operations will occur at Kennedy Space Center's Launch Complex 39A, the same pad that launched Apollo 11 and regularly hosts SpaceX's crew missions to the ISS. The symbolic continuity between Apollo's departure point and Artemis's beginning underscores how Gateway bridges past and future lunar exploration.

After liftoff, the Falcon Heavy's upper stage will perform a series of engine burns to place PPE-HALO on its trans-lunar trajectory. Over the following weeks, flight controllers will monitor systems, test communications, and verify that all subsystems are functioning correctly. The year-long transit provides time to characterize radiation exposure, test autonomous operations, and fine-tune Gateway's systems before crew arrival.

When the station reaches its NRHO destination in late 2028, ground controllers will activate Gateway's full operational capabilities. The PPE's electric thrusters will maintain the station's orbit, solar arrays will generate power, and communication systems will establish data links with Earth and await the arrival of lunar landers. Gateway will be open for business.

Imagine looking up at the Moon in 2026 and knowing that humanity's first cislunar outpost is sweeping through its elliptical orbit, waiting for the Artemis III crew to arrive. That Moon, which has looked the same to every human who's ever lived, will become a destination again - not for a brief visit, but as the focus of sustained exploration enabled by permanent infrastructure.

Gateway represents a choice about how humanity expands beyond Earth. We could have pursued the Apollo model: impressive flags-and-footprints missions that prove we can reach distant destinations but don't establish lasting presence. Instead, we're building infrastructure - expensive, complex, sometimes frustrating infrastructure that makes the next mission easier than the last.

The ISS taught us that sustained presence in space returns dividends that brief missions never can. Medical insights, materials discoveries, operational lessons, and international cooperation emerged from decades of continuous occupation. Gateway promises similar returns for cislunar space: a platform where knowledge accumulates, where systems improve with each mission, where international partners commit to multi-decade collaboration.

When the first crew boards Gateway during Artemis IV, they'll inherit decades of spaceflight experience embodied in systems designed by thousands of engineers across a dozen nations. They'll look down at the Moon - closer than anyone has been since Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt departed Taurus-Littrow Valley in December 1972 - and know they're there to stay. Not as temporary visitors, but as the vanguard of a permanent human presence in the Earth-Moon system.

Gateway's success isn't measured by its initial missions alone. Like the transcontinental railroad, the Interstate Highway System, or the Internet, Gateway's value will accumulate as people find uses that its designers never anticipated. Commercial ventures, scientific discoveries, and international cooperation will emerge from infrastructure that makes cislunar access routine rather than heroic.

We're building Gateway because exploration requires infrastructure. Because temporary presence yields to permanent settlement when you invest in lasting capability. Because the future we're building includes human activity throughout the inner solar system, and that future needs staging points, laboratories, and gathering places where crews from many nations work toward common goals.

The Lunar Gateway isn't just a space station. It's humanity's first permanent structure beyond Earth orbit, the hub that will support returning to the Moon and eventually reaching Mars. When you look at the Moon in 2026, you'll be looking at the next chapter of human space exploration - one that doesn't end when the mission clock runs out, but continues for decades as we learn to live and work in deep space.

The station orbiting above those ancient craters isn't the destination. It's the doorway.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.