Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: NASA's Parker Solar Probe, traveling at record-breaking speeds of 430,000 mph, is revolutionizing solar science by directly sampling the Sun's corona and solving decades-old mysteries about solar wind and space weather.

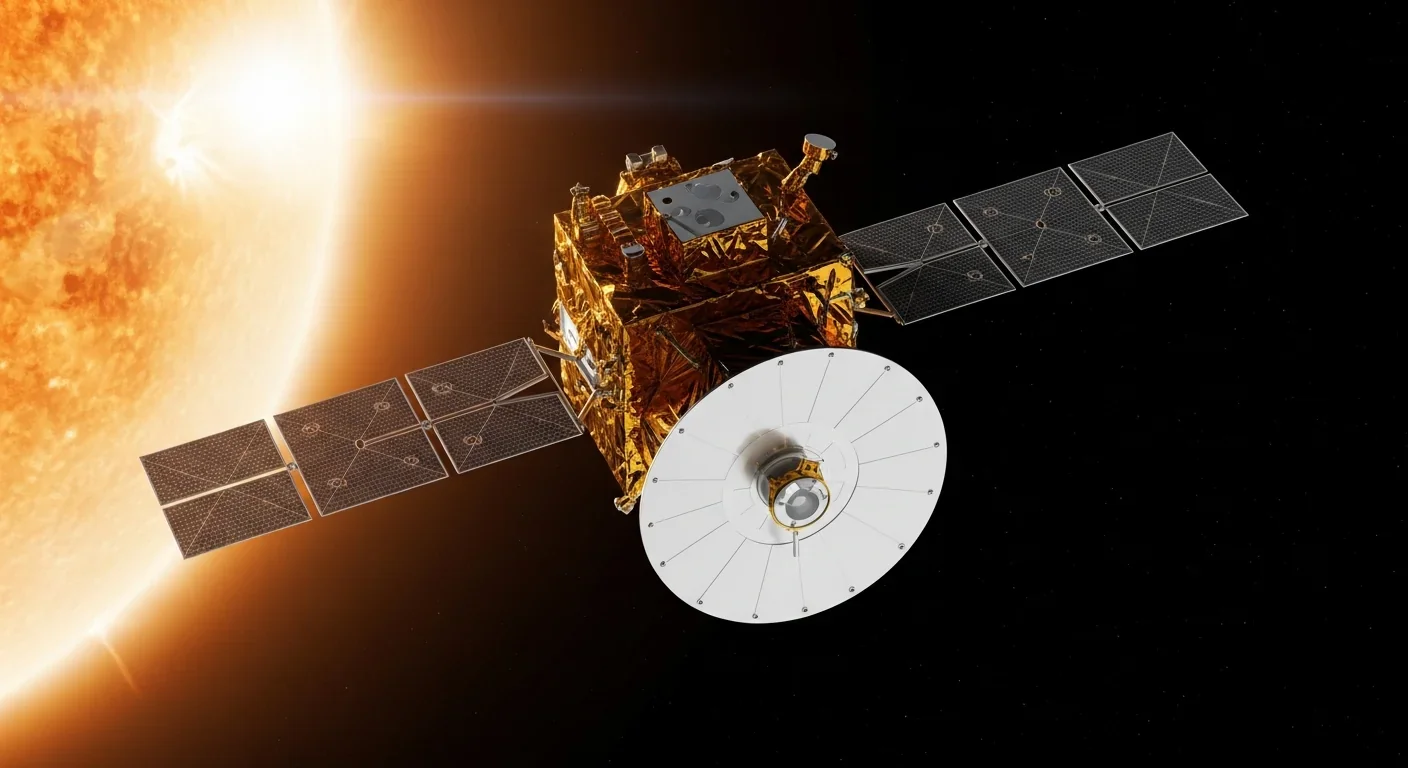

On Christmas Eve 2024, while most of Earth was celebrating, a refrigerator-sized spacecraft made history 3.8 million miles from the Sun's surface. NASA's Parker Solar Probe had just survived humanity's closest encounter with a star, hurtling through the solar corona at a mind-bending 430,000 miles per hour. The probe didn't just survive temperatures exceeding 2,500°F and radiation that would fry any unprotected electronics instantly. It sent back a simple beacon tone that meant everything: "I'm alive, and I've got data."

This wasn't just another space milestone to add to humanity's collection. Parker Solar Probe represents something far more profound: our species' audacious attempt to touch a star and live to tell the tale. Since its launch in August 2018, this $1.5 billion mission has been systematically rewriting our understanding of the Sun, solving mysteries that have puzzled scientists for decades, and revealing phenomena that nobody expected to find.

The numbers alone defy comprehension. At its closest approach, Parker Solar Probe flies just 3.8 million miles from the Sun's visible surface, about seven times closer than Mercury's orbit. At that distance, the spacecraft endures temperatures hot enough to melt steel, radiation intense enough to scramble any computer, and gravitational forces that accelerate it to speeds no human-made object has ever achieved before.

The secret to Parker's survival lies in its revolutionary Thermal Protection System, a heat shield that represents one of the greatest engineering achievements in spaceflight history. Just 4.5 inches thick and 8 feet in diameter, this carbon-carbon composite shield maintains a comfortable 85°F behind it while its Sun-facing surface reaches 2,500°F. The shield consists of two carbon plates sandwiching a lightweight carbon foam core, a design so effective that the instruments behind it require heaters to stay warm, despite being millions of miles from the Sun.

But the heat shield is only part of the story. Parker's autonomous control system represents another breakthrough. When you're that close to the Sun, there's no time to wait for instructions from Earth. A command would take about 13 minutes to travel from mission control to the spacecraft, far too long when you're flying through million-degree plasma at 120 miles per second. So Parker thinks for itself, using sensors to detect if any part of the spacecraft is exposed to direct sunlight and automatically adjusting its orientation to keep everything safely in the heat shield's shadow.

The probe's speed itself becomes a survival mechanism. Moving at 430,000 mph during perihelion, Parker doesn't linger in any one spot long enough for heat to build up catastrophically. It's like quickly passing your finger through a candle flame, if the flame was 2 million degrees and your finger was a billion-dollar spacecraft.

At 430,000 mph, Parker Solar Probe could fly from New York to London in under 30 seconds, making it the fastest human-made object in history.

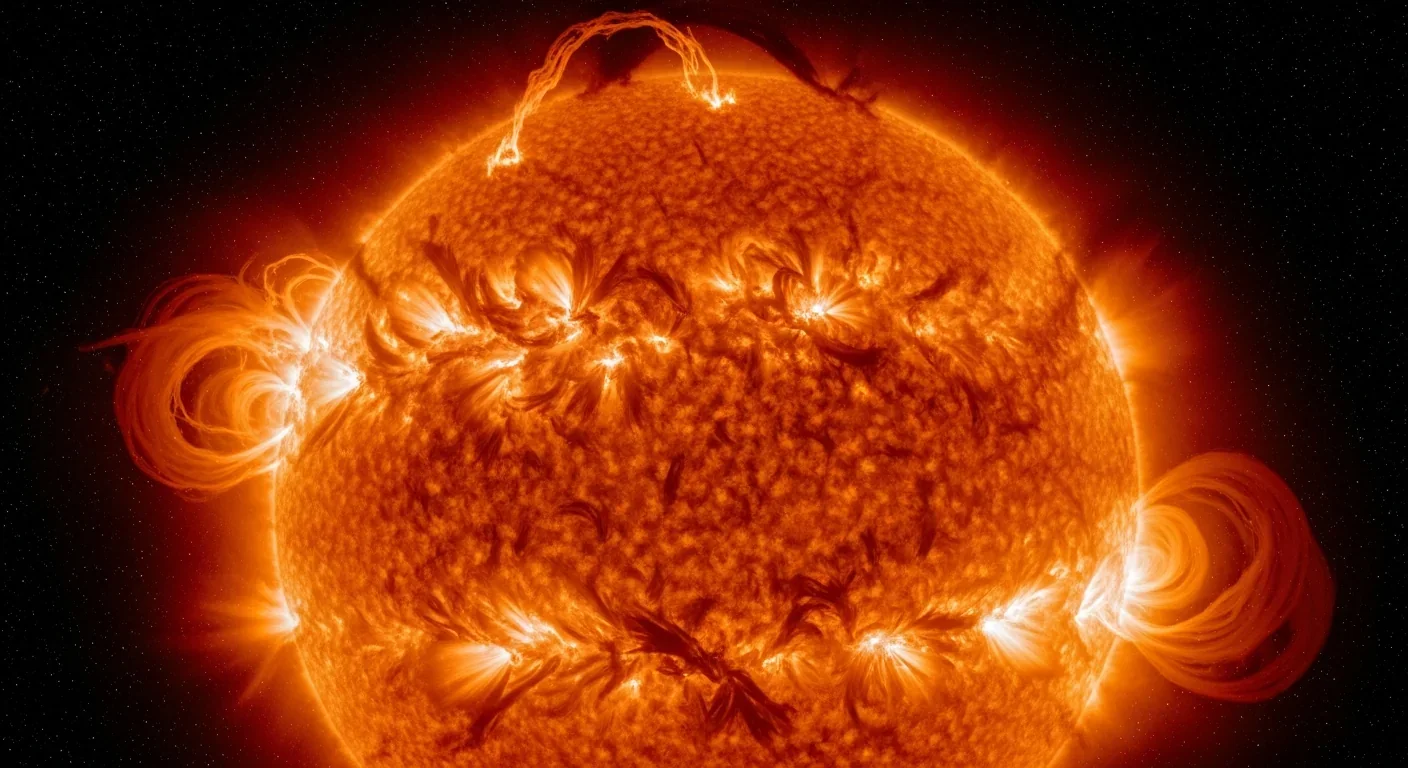

Before Parker Solar Probe, solar scientists faced a paradox that seemed to violate the laws of physics. The Sun's visible surface, the photosphere, maintains a temperature around 10,000°F. Logic would suggest that as you move away from this heat source, temperatures should drop. Instead, the corona, the Sun's outer atmosphere, blazes at temperatures exceeding 2 million degrees Fahrenheit, hundreds of times hotter than the surface below.

This coronal heating problem has haunted solar physics since the 1940s when Swedish physicist Hannes Alfvén first identified it. Scientists proposed dozens of theories, from magnetic waves to tiny explosions called nanoflares, but without direct measurements from within the corona itself, these remained educated guesses.

The solar wind presented another puzzle. This stream of charged particles flows from the Sun at speeds ranging from 200 to 500 miles per second, but scientists couldn't explain what accelerated these particles to such velocities. The wind starts subsonic in the corona and somehow reaches supersonic speeds by the time it passes Earth. Something was happening in that transition zone, but what?

Then there were the solar storms, massive eruptions that can hurl billions of tons of magnetized plasma toward Earth at millions of miles per hour. These coronal mass ejections can knock out satellites, disrupt GPS systems, damage power grids, and expose astronauts to dangerous radiation. Yet predicting when and where they'll occur remained nearly impossible because we didn't understand the magnetic processes that trigger them.

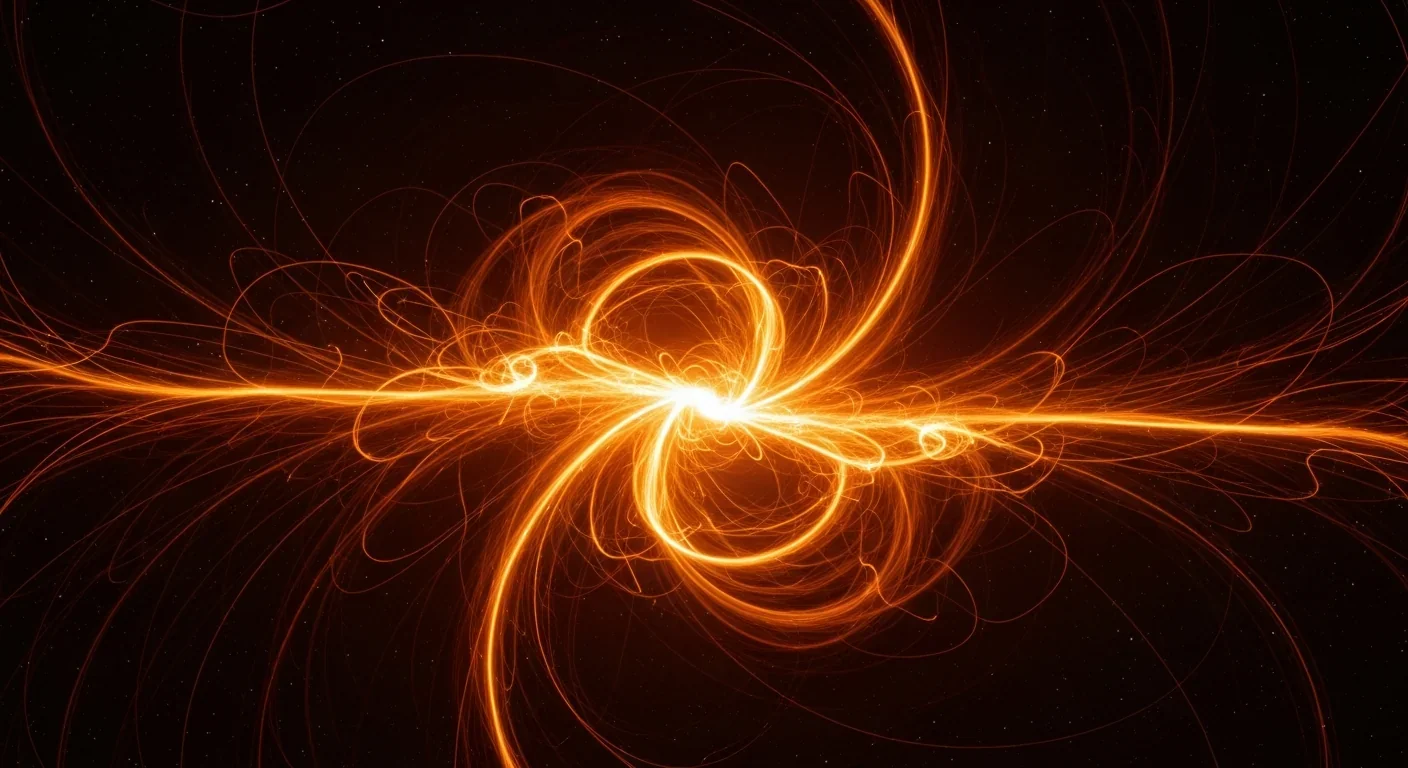

Parker's most surprising discovery came almost immediately after it began science operations: magnetic switchbacks. These are sudden, dramatic reversals in the Sun's magnetic field that whip back on themselves like a garden hose being shaken. While the Ulysses spacecraft had spotted hints of these phenomena in the 1990s, Parker revealed them to be ubiquitous features of the solar wind near the Sun.

These switchbacks aren't just magnetic curiosities. Dr. Stuart Bale from UC Berkeley, principal investigator for Parker's FIELDS instrument, explains that these structures appear to be fundamental to how the Sun accelerates the solar wind. The switchbacks create turbulence and waves that heat and push particles outward, potentially solving the decades-old mystery of solar wind acceleration.

"The switchbacks we're seeing are far more prevalent than anyone expected. They appear to be a fundamental feature of how the Sun releases energy into space."

- Dr. Stuart Bale, UC Berkeley

In April 2021, Parker achieved another milestone by becoming the first spacecraft to fly through the Sun's corona, crossing what scientists call the Alfvén critical surface. This boundary marks where the solar wind becomes fast enough to break free from the Sun's magnetic field. The probe found this surface isn't smooth like scientists expected but wrinkled and dynamic, with huge structures called pseudostreamers creating magnetic highways for particles to race along.

Parker's Wide-field Imager instrument has captured unprecedented views of the solar wind being born. The images show bright streamers of material flowing away from the Sun, revealing the solar wind's structure before it becomes the turbulent stream we detect at Earth. These observations are helping scientists understand how the wind evolves as it travels through the solar system.

Every time Parker Solar Probe swings around the Sun, it breaks its own speed record. The latest perihelion on December 24, 2024, saw the probe reach 430,000 mph, making it not just the fastest spacecraft but the fastest human-made object in history. To put this in perspective, at that speed you could fly from New York to London in under 30 seconds, or circle Earth's equator in about 3.5 minutes.

This incredible velocity isn't achieved through powerful rockets but through a carefully choreographed orbital dance. Parker uses Venus's gravity like a cosmic brake, performing seven flybys over its mission lifetime. Each Venus encounter adjusts Parker's orbit, allowing it to fall closer to the Sun where gravity accelerates it to progressively higher speeds.

The physics behind this acceleration follows Kepler's laws of planetary motion. As Parker falls toward the Sun, it converts gravitational potential energy into kinetic energy, just like a ball rolling down a hill. But unlike a ball, Parker maintains its energy in the vacuum of space, using Venus's gravity to gradually lower its orbit rather than fighting against the Sun's pull with fuel-hungry rockets.

The probe's extreme speed creates unique scientific opportunities. Moving so fast through the solar corona, Parker can sample different regions rapidly, building a three-dimensional picture of solar structures that would be impossible from Earth-based observations. It's like the difference between looking at a photograph of a forest and actually walking through it, feeling the trees, and understanding its depth.

Parker Solar Probe's discoveries aren't just advancing pure science; they're providing crucial information for protecting our increasingly technology-dependent civilization. Space weather events cost the global economy an estimated $1-2 billion annually through satellite failures, power grid disruptions, and communication outages.

A single major solar storm could cause over $2 trillion in damages globally, affecting everything from GPS navigation to credit card transactions.

The probe's measurements of the solar wind's acceleration mechanisms are helping scientists develop better models for predicting when dangerous solar storms will strike Earth. By understanding how magnetic switchbacks and other phenomena influence particle acceleration, forecasters can provide more accurate warnings to satellite operators and power companies.

One of Parker's most practical discoveries involves coronal mass ejections. The probe has observed these massive eruptions from within, revealing how they form and accelerate. This inside view is helping scientists understand the warning signs that precede major space weather events, potentially extending forecast lead times from hours to days.

The mission has also revealed that the solar wind is far more complex than previously thought. Instead of a steady stream, Parker found a turbulent, dynamic flow filled with waves, eddies, and jets. Understanding this complexity is crucial for protecting future Mars missions, where astronauts will be exposed to solar radiation without Earth's protective magnetic field.

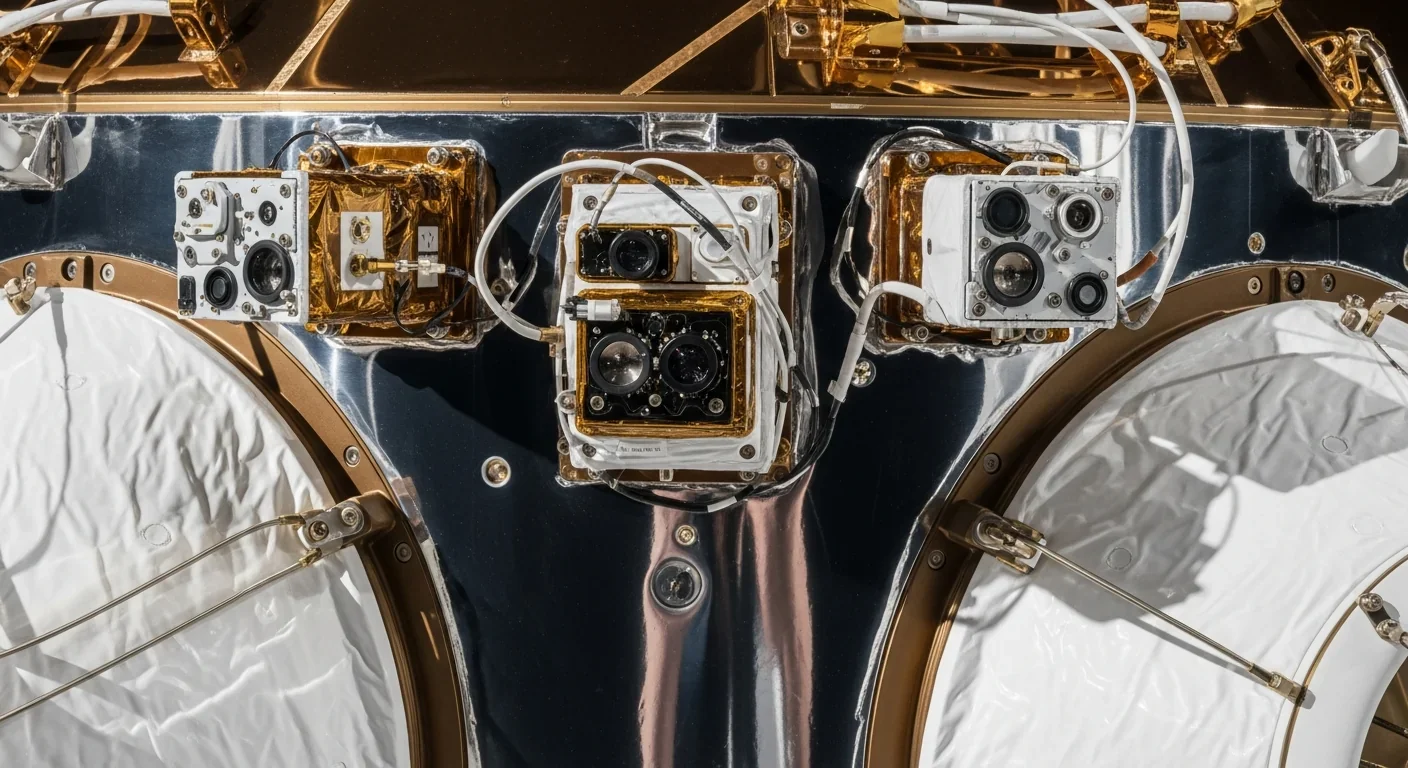

Beyond the heat shield, Parker Solar Probe incorporates technologies that push the boundaries of what's possible in spacecraft design. The probe's solar panels represent a particular challenge. Most spacecraft solar panels would melt instantly at Parker's operating temperatures, but the probe needs power to run its instruments and communications systems.

Engineers solved this by creating retractable solar arrays that extend fully when Parker is farther from the Sun but withdraw behind the heat shield during close approaches, leaving only a small portion exposed. This exposed section uses a unique cooling system, circulating a gallon of deionized water through titanium tubes to carry heat away from the panels. It's essentially a radiator system operating in the most extreme environment imaginable.

The FIELDS instrument, which measures electric and magnetic fields, presented another engineering challenge. Its sensors need to extend beyond the heat shield's protection to make measurements, exposing them to the full fury of the solar environment. The solution involved creating sensors from niobium C-103, a refractory metal alloy that maintains its properties at extreme temperatures, and coating them with white ceramic to reflect as much heat as possible.

Communication with Parker during perihelion passages pushes technology to its limits. The Deep Space Network has to track a spacecraft moving at unprecedented speeds while it's partially hidden behind the Sun's corona. The probe stores data during close approaches when communication is impossible, then transmits it back to Earth during the cooler parts of its orbit, using a sophisticated prioritization system to ensure the most valuable science data gets sent first.

The Parker Solar Probe holds the distinction of being the first NASA mission named after a living person. Dr. Eugene Parker, who passed away in 2022 at age 94, revolutionized solar physics in the 1950s when he predicted the existence of the solar wind, a concept so radical that reviewers initially rejected his paper.

"The solar wind was pure theory when I proposed it. To see the spacecraft bearing my name actually flying through the solar wind and proving things we only imagined, it's just remarkable."

- Dr. Eugene Parker (1927-2022)

Parker lived to see his namesake spacecraft launch and return its first data, validating theories he'd proposed decades earlier. His prediction of the solar wind was just one of many contributions; he also theorized about the Sun's magnetic field, the acceleration of cosmic rays, and the dynamics of the solar corona, many of which Parker Solar Probe is now confirming or refining.

The mission carries a memory card containing the names of more than 1.1 million people who signed up to symbolically travel to the Sun, along with photos of Parker and a copy of his groundbreaking 1958 paper on solar wind. It's a fitting tribute to a scientist whose ideas were once considered too radical but are now fundamental to our understanding of stars.

Parker Solar Probe's mission is far from over. The spacecraft will continue making progressively closer approaches through 2025, with several more perihelia at the minimum 3.8 million mile distance. Each pass provides new data, and scientists expect the most extreme conditions and potentially the most significant discoveries are yet to come.

Future orbits will take Parker through different regions of the corona during various phases of the solar cycle. The Sun follows an 11-year cycle of activity, and Parker launched during solar minimum when the Sun was relatively quiet. As we approach solar maximum in 2025, the probe will witness increased solar flares, more frequent coronal mass ejections, and a more complex magnetic environment.

The mission's extended phase could last until 2025 or beyond, limited primarily by the probe's fuel supply needed for attitude control. Even after the primary mission ends, Parker's orbit will remain stable for millennia, making it humanity's eternal monument circling our star.

Scientists are already planning complementary missions. The European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter, launched in 2020, provides a different perspective, using remote sensing instruments to image the Sun's poles. Together with Parker's in-situ measurements, these missions are creating an unprecedented understanding of our star's behavior.

Parker Solar Probe's discoveries extend beyond just our Sun. By understanding how our star works, astronomers can better interpret observations of distant stars throughout the universe. The magnetic switchbacks Parker discovered might be common features of all stars, affecting how they lose mass and angular momentum over time.

The probe's measurements of particle acceleration mechanisms are helping scientists understand cosmic rays, high-energy particles that bombard Earth from across the universe. Some of these particles originate from our Sun, but others come from supernovae, black holes, and other extreme cosmic events. Parker's observations provide a laboratory for understanding acceleration processes that occur throughout the cosmos.

The mission is also reshaping our search for habitable exoplanets. Understanding how stellar wind and radiation affect planetary atmospheres is crucial for determining whether distant worlds could support life. Parker's data helps scientists model how different types of stars might strip away planetary atmospheres or deliver the energy needed for biological processes.

Parker's discoveries about solar wind could help identify which exoplanets retain their atmospheres and potentially harbor life, narrowing our search for Earth-like worlds.

As we stand at the threshold of becoming a multi-planetary species, understanding our Sun becomes not just scientifically interesting but essential for survival. Future missions to Mars and beyond will take humans outside Earth's protective magnetosphere, exposing them to the full force of solar radiation. Parker's discoveries about solar particle acceleration and space weather will literally help keep future astronauts alive.

The technologies developed for Parker Solar Probe are already finding applications elsewhere. The heat-resistant materials created for the mission have potential uses in hypersonic aircraft, industrial processes, and even fusion reactors. The autonomous control systems that keep Parker safe could be adapted for future missions to Venus or robots working in extreme environments on Earth.

Perhaps most importantly, Parker Solar Probe represents humanity at its most audacious. In an era when many feel overwhelmed by earthly challenges, this mission reminds us what we're capable of when we combine human ingenuity, international collaboration, and the courage to attempt the impossible. We've built a machine that can touch a star and survive, answering questions that have puzzled us for generations while revealing mysteries we didn't even know existed.

The 2020s are becoming a golden age for solar physics. With Parker Solar Probe touching the Sun, Solar Orbiter imaging its poles, and ground-based telescopes like the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope providing unprecedented resolution of the solar surface, we're assembling a complete picture of how our star works.

This knowledge arrives at a crucial time. As our society becomes increasingly dependent on satellites for communication, navigation, and Earth observation, understanding and predicting space weather becomes essential infrastructure protection. The next major solar storm could cost trillions in damages if we're unprepared, but Parker's discoveries are helping us build resilience.

The mission also demonstrates the power of long-term thinking in science. Parker Solar Probe was first proposed in 1958, the same year Eugene Parker predicted the solar wind. It took 60 years of technological advancement to make the mission possible, showing that some scientific questions require patience, persistence, and multiple generations of scientists and engineers working toward a common goal.

As Parker Solar Probe continues its lonely orbit, diving repeatedly through hell and emerging with treasures of knowledge, it carries with it the hopes and dreams of everyone who has ever looked up at the Sun and wondered how it works. In touching our star, we've not only solved old mysteries but discovered new ones, ensuring that the next generation of scientists will have even more fascinating questions to pursue. The probe that shouldn't be possible is doing the impossible, and in the process, expanding the boundaries of human achievement.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.