Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

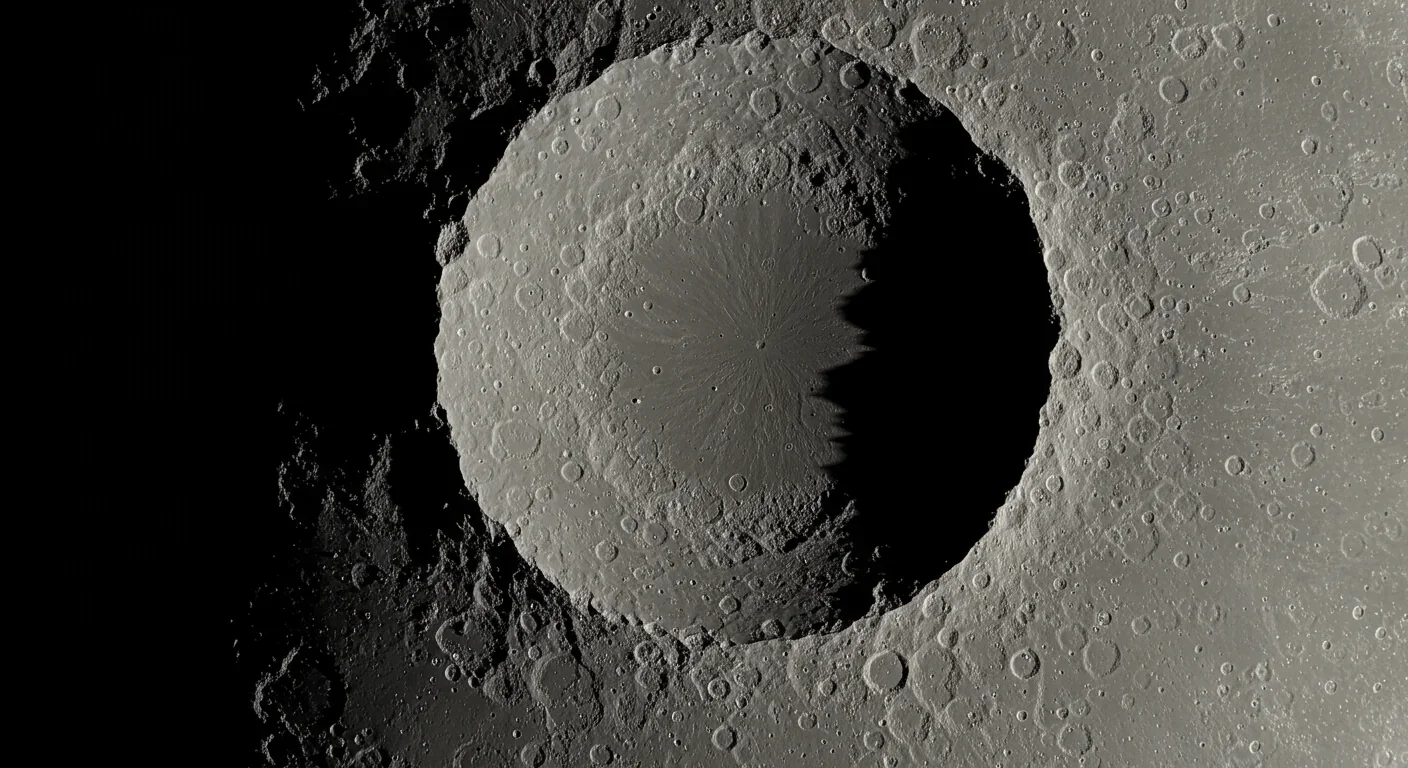

TL;DR: The South Pole-Aitken basin, the Moon's largest impact crater at 2,500 km wide, holds secrets about lunar and planetary formation. Recent Chang'e-6 samples dated the 10-km-deep basin to 4.25 billion years ago and revealed it may expose mantle material, making it a prime target for future Artemis missions.

Within the next decade, astronauts landing on the Moon's far side will stand at the edge of a wound so deep it nearly killed our celestial companion. The South Pole-Aitken basin isn't just the Moon's largest crater - at 2,500 kilometers across, it's the largest confirmed impact scar in the entire solar system. Four billion years ago, an asteroid the size of a small planet slammed into the lunar far side with such devastating force that it may have literally rolled the Moon on its axis, shifting its entire mass to compensate for the material blown into space.

What makes this ancient basin extraordinary isn't just its size. The impact punched through 10 kilometers of lunar crust, potentially exposing material from the Moon's mantle - the layer between crust and core that normally remains locked away from scientific scrutiny. For planetary scientists, it's like having a natural drill hole into the Moon's interior, offering a rare glimpse at the building blocks that formed not just our nearest neighbor, but rocky worlds throughout the solar system.

Recent breakthroughs from China's Chang'e-6 mission, which returned the first samples from the lunar far side in 2024, are revolutionizing our understanding of this geological treasure. Scientists analyzed 1,600 fragments from just 5 grams of lunar soil, discovering that the basin formed precisely 4.25 billion years ago - placing it squarely within a violent period when asteroids bombarded the inner solar system. The samples contained norite, a coarse-grained igneous rock that tells the story of the Moon's molten past, and revealed evidence of not one but two major impact events that reshaped this region.

The South Pole-Aitken basin is so massive that if you could walk its perimeter at a steady pace, it would take you roughly three months of continuous walking to complete the circuit.

The South Pole-Aitken basin spans roughly the distance from Texas to Washington, DC, yet from Earth we can barely see it. Located on the lunar far side, the side that perpetually faces away from our planet, the basin appears only as a jagged mountain chain along the Moon's southern edge. This positioning is no accident - it may explain one of the Moon's greatest mysteries.

Look at the Moon tonight and you'll see dark patches called maria, vast plains of solidified lava that flooded ancient impact basins. The near side is covered with them. But the far side, revealed only when spacecraft first orbited the Moon in the 1960s, tells a radically different story. It's heavily cratered, pale, and almost completely devoid of maria. For decades, planetary scientists have wondered: why do the Moon's two faces look so different?

The South Pole-Aitken impact may be the culprit. When that massive asteroid hit, it didn't just excavate a crater - it fundamentally altered the Moon's internal heat distribution. The tremendous energy released by the impact could have concentrated heat-generating elements on the Moon's near side, triggering prolonged volcanic activity that filled nearside basins with the dark lava we see today. Meanwhile, the far side remained cold, preserving its ancient, heavily cratered surface.

Think of it this way: the impact was so violent it essentially rewired the Moon's internal plumbing system, determining where volcanism would occur for the next billion years. We're still living with the consequences of that ancient collision every time we look up at the Moon's familiar face.

Something strange lurks beneath the South Pole-Aitken basin, and scientists have been puzzling over it since 2019. Using gravity-mapping data from NASA's GRAIL mission, researchers discovered a massive anomaly buried hundreds of miles below the crater floor - a concentration of material so dense it's dragging the basin down by more than half a mile.

"Imagine taking a pile of metal five times larger than the Big Island of Hawaii and burying it underground. That's roughly how much unexpected mass we detected."

- Peter B. James, Planetary Geophysicist, Baylor University

What is this mysterious mass? The leading theory suggests it's the metallic core of the original impactor, still embedded in the lunar mantle after 4 billion years. Computer simulations show that under the right conditions, an asteroid's iron-nickel core could disperse into the Moon's upper mantle during impact rather than sinking all the way to the lunar core. If this interpretation is correct, we're detecting the fossilized remains of the very asteroid that created the basin - a cosmic crime scene where the murder weapon remains buried at the scene.

An alternative explanation proposes that the mass represents dense oxides that accumulated during the final stages of the Moon's magma ocean solidification. When the Moon was young and molten, heavier materials sank while lighter ones floated to form the crust. This gravitational anomaly might be a dense pocket of these settling materials, preserved in place since the Moon's earliest days.

Either way, the anomaly offers scientists a unique window into processes that shaped not just the Moon, but all rocky planets during the solar system's chaotic youth.

For decades, scientists believed they understood how the South Pole-Aitken basin formed: a massive asteroid struck from the south at a low angle, creating the basin's characteristic elongated shape. But in 2025, researchers led by Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna at the University of Arizona upended this model.

By carefully analyzing the basin's teardrop-shaped structure, the team discovered something surprising - the crater actually narrows toward the south, not the north. This means the impactor came from the opposite direction than previously thought, traveling from north to south rather than south to north.

Why does the impact direction matter? Because it completely changes where debris from the collision would have landed. Giant impacts don't distribute their ejecta evenly. Material excavated from deep within the Moon tends to pile up on the downrange side of the crater - the direction the asteroid was traveling. If the impact came from the north, that means the southern rim of the basin is buried under a thick blanket of material that was once deep inside the Moon.

This revelation has profound implications for NASA's Artemis program, which plans to land astronauts near the basin's southern rim. Instead of exploring typical lunar crust, Artemis crews will be walking on ground that potentially contains material from the Moon's mantle - rocks that formed deep underground and have never been accessible to study. It's as if the impact did the drilling for us, excavating and delivering to the surface exactly the samples scientists most want to analyze.

Hidden within the basin's western edge is another clue to the Moon's evolution. Spacecraft have detected elevated concentrations of thorium, a radioactive element closely associated with a suite of materials scientists call KREEP - an acronym for potassium (K), rare earth elements (REE), and phosphorus (P).

KREEP sounds like something from a science fiction movie, but it's actually a geochemical signature left over from the Moon's formation. When the Moon's global magma ocean slowly cooled and crystallized, most minerals solidified and sank or floated based on their density. But certain elements, including those that make up KREEP, resisted crystallization. They remained liquid, accumulating in the last remaining pools of magma like the final dregs in a separating mixture.

These KREEP-rich materials became important for the Moon's subsequent evolution because they're radioactive. Radioactive decay generates heat, and heat drives geological activity. On the Moon's near side, KREEP concentrations fueled volcanic eruptions that created the dark maria. But the far side remained cold and inactive.

The presence of KREEP on the western edge of the South Pole-Aitken basin suggests something fascinating: the asteroid struck right at a transitional boundary where some KREEP-rich material still existed beneath the far side's crust. The impact excavated and redistributed this material, creating a chemical map that records the Moon's internal structure at the moment of collision.

Scientists now believe the far side's crust gradually thickened over time, compressing the remnants of the magma ocean and forcing radioactive materials toward the thinner near-side crust. This uneven development dictated where volcanic activity could occur - a process triggered or accelerated by the energy released during the South Pole-Aitken impact itself.

The energy released by the South Pole-Aitken impact was roughly equivalent to 10 billion Hiroshima bombs detonating simultaneously - enough to vaporize rock and create a temporary atmosphere of molten debris.

When China's Chang'e-6 spacecraft touched down in the Apollo crater, located within the South Pole-Aitken basin, on June 1, 2024, it made history as the first mission to sample the lunar far side. The 2 kilograms of soil and rocks it returned to Earth have already transformed our understanding of the basin's history.

Lead-lead isotopic dating - a technique that measures ratios between different lead isotopes - revealed two distinct impact ages in the samples: 4.25 billion years and 3.87 billion years. The older impact showed signs of crystallization, identifying it as the original basin-forming event. The younger age likely represents a subsequent major impact that occurred within the already-existing basin, adding another layer to this region's violent history.

Among the 1,600 analyzed fragments, researchers identified 20 clasts of norite, a coarse-grained igneous rock common in Earth's crust but significant on the Moon. Norite forms from slowly cooling magma, and its presence confirms that the impact created a massive melt sheet - a temporary ocean of molten rock that gradually solidified. This melt sheet would have been kilometers deep, taking thousands or even millions of years to completely crystallize.

The samples also help calibrate the ages of other lunar features. By precisely dating material from the South Pole-Aitken basin, scientists can better estimate the ages of other impact craters by comparing their appearance and degradation state. It's like establishing a chronological anchor point that allows researchers to construct a more accurate timeline of lunar and solar system history.

"The analyses to be carried out on lunar samples from the hidden side of our satellite have just begun."

- Chen Yi, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Chen Yi of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who led the analysis, emphasized that these samples represent just the beginning. Many research groups worldwide are studying the returned material, and more discoveries are inevitable.

The South Pole-Aitken basin serves as one of the best-preserved examples of the catastrophic impacts that shaped all rocky planets and moons during the solar system's early history. While larger impacts almost certainly occurred on Earth, Mars, and other worlds, erosion, plate tectonics, and volcanic resurfacing have erased most evidence of these ancient collisions.

The Moon, lacking atmosphere, water, and active geology, preserves impacts in a way Earth cannot. The South Pole-Aitken basin is effectively a 4-billion-year-old time capsule, frozen at the moment of its creation. By studying it, scientists can reconstruct the conditions, energies, and consequences of planet-scale collisions - events that determined whether worlds became hospitable to life or remained barren rocks.

The basin's age places it near or during the Late Heavy Bombardment, a period roughly 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago when the inner solar system experienced an intense spike in asteroid and comet impacts. This bombardment delivered water and organic materials to Earth, potentially providing the raw ingredients necessary for life to emerge. Understanding when the South Pole-Aitken basin formed helps scientists determine when this bombardment began and whether it was a brief, intense event or a longer, more gradual process.

The implications extend beyond academic curiosity. As humanity plans permanent lunar bases and eventual missions to Mars, understanding impact processes becomes crucial for assessing risks. Large asteroids still exist in Earth-crossing orbits, and while planet-killer impacts are rare on human timescales, they remain a threat worth studying. The Moon serves as a nearby laboratory where we can examine impact effects in detail without needing to simulate them.

NASA's Artemis program and China's ongoing lunar exploration missions are converging on the South Pole-Aitken basin, recognizing it as one of the Moon's most scientifically valuable regions. The basin's southern rim, where Artemis astronauts may land, offers access to permanently shadowed craters that could harbor water ice - a crucial resource for sustained human presence - while simultaneously providing geological access to deep lunar materials.

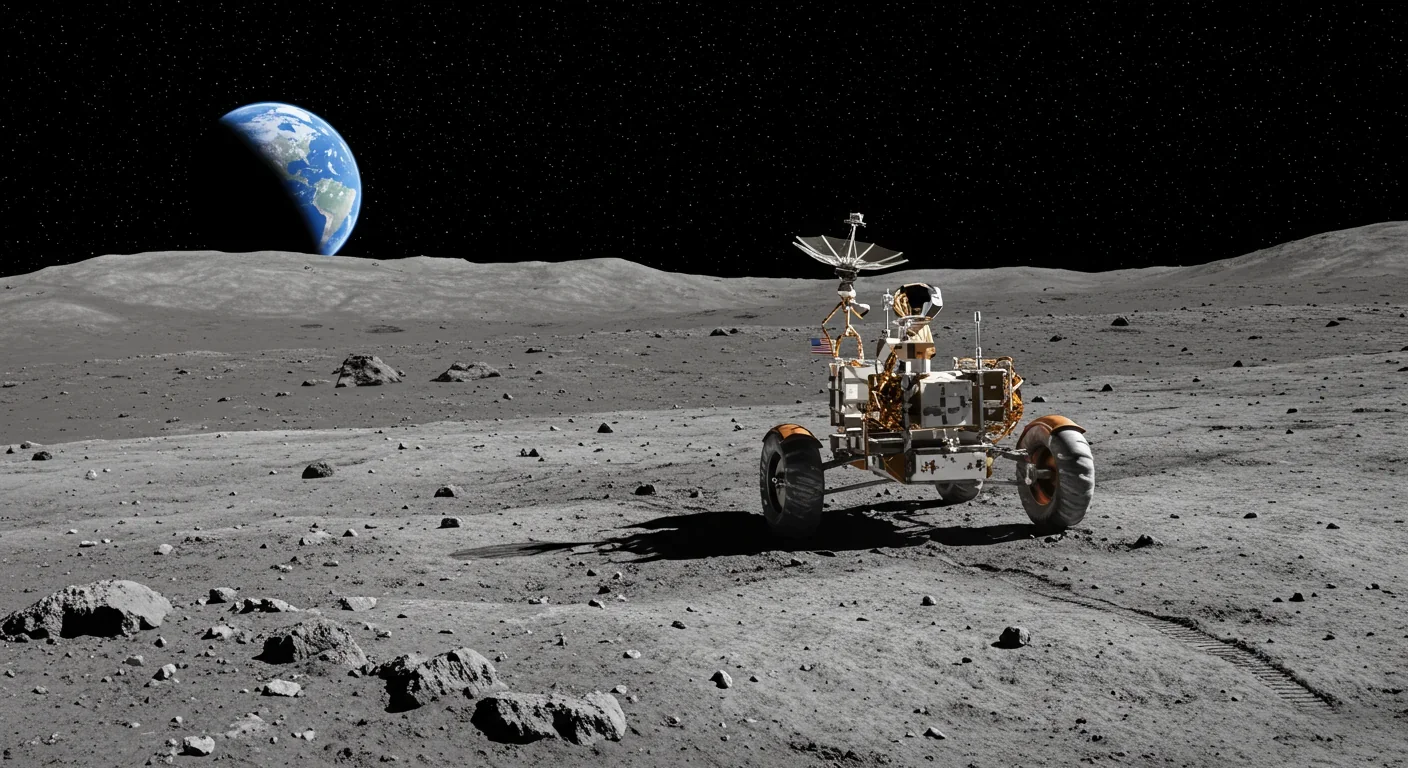

China's Chang'e-4 mission, which landed the Yutu-2 rover in Von Kármán crater within the basin in 2019, has been exploring this region for years. The rover has traveled across impact ejecta, analyzed soil composition, and captured high-resolution images of the basin floor. Its discoveries of minerals like olivine and low-calcium pyroxene provided some of the first direct evidence that the impact excavated mantle material.

Future missions will build on these foundations. NASA is developing the South Pole-Aitken Basin Sample Return and Exploration (SPARX) mission, designed specifically to collect and return samples from deep within the basin where mantle material is most likely to be found. If successful, SPARX will provide scientists with pieces of the lunar mantle for the first time - rocks that formed deep within the Moon and can reveal its internal composition and structure.

The basin also attracts attention from resource perspective. Its permanently shadowed regions near the lunar south pole may contain substantial water ice deposits, potentially accumulated over billions of years from comet impacts and solar wind interactions. This ice could be extracted and used for life support, radiation shielding, and even rocket fuel, making the basin a strategic location for future lunar bases.

But perhaps the most exciting prospect is what astronauts will see when they stand at the basin's rim. Looking out across a crater larger than the Mediterranean Sea, they'll be viewing one of the solar system's most significant geological features - a testament to the violent processes that forged worlds and created the conditions for planets like Earth to eventually harbor life.

Standing at the basin's edge, an astronaut could see the opposite rim only if the Moon's curvature didn't block the view. In reality, the horizon would appear about 2.4 kilometers away - the crater is simply too large to comprehend from any single vantage point.

Every new detail scientists uncover about the South Pole-Aitken basin refines our understanding of how planets form and evolve. The Moon serves as a reference point for dating other surfaces throughout the inner solar system. By establishing precise ages for major lunar features, researchers can estimate the ages of craters on Mars, Mercury, and asteroids by comparing their appearance and degradation.

The basin's mantle material, if confirmed, would provide the first direct samples of a terrestrial body's interior obtained without expensive drilling operations. On Earth, the deepest hole ever drilled - the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia - reached just 12 kilometers, barely scratching the surface of our 6,371-kilometer-radius planet. The South Pole-Aitken impact did in an instant what human technology has never accomplished: drilling through the entire crust to access mantle material.

Studying these samples helps scientists understand planetary differentiation - the process by which planets separate into distinct layers based on density. When worlds form from the collision and accretion of smaller bodies, they start relatively homogeneous. Heating from radioactive decay and impact energy melts the interior, allowing dense materials like iron to sink toward the center while lighter materials float to form a crust. The Moon's mantle represents the intermediate layer, and its composition constrains models of how this separation occurred.

The basin also informs our understanding of impact processes themselves. How much energy is required to excavate mantle material? At what angle and velocity do asteroids need to strike to create basins of different shapes? How does the size of the impactor relate to the size of the resulting crater? These questions have implications for assessing impact risks to Earth and for understanding the cratering we observe on worlds throughout the solar system and beyond.

More than four billion years after a massive asteroid carved the South Pole-Aitken basin into the Moon's far side, this ancient wound continues to reveal secrets about our cosmic neighborhood. Each new mission, whether robotic or crewed, adds pieces to a puzzle that spans the entire history of the solar system.

The samples already returned by Chang'e-6 are being studied in laboratories worldwide, with new discoveries emerging regularly. Future missions by NASA, China, and other space agencies will bring back more material from different parts of the basin, allowing scientists to map its composition in three dimensions and trace the distribution of mantle-derived rocks across the crater floor.

Advanced instruments on upcoming lunar orbiters will map the basin's gravity field, magnetic anomalies, and surface composition at unprecedented resolution. Ground-penetrating radar could reveal the structure of the mysterious mass buried beneath the basin floor, finally determining whether it's the impactor's core or a byproduct of the Moon's magma ocean.

Within the next decade, astronauts will walk on ground that last saw visitors 4 billion years ago - not tourists, but asteroid fragments traveling at tens of kilometers per second. They'll collect rocks that formed in the Moon's interior, examine impact melt that once flowed like water, and stand at the boundary between two fundamentally different lunar terrains.

The South Pole-Aitken basin reminds us that planetary surfaces aren't static. They're shaped by violence, transformed by collisions, and continually evolving. The impact that created this massive scar helped make the Moon the world we see today - a world that, in turn, stabilizes Earth's rotation and creates the tides that shaped life's evolution. In understanding this ancient impact, we're not just learning about the Moon. We're learning about ourselves and the improbable series of cosmic accidents that made our existence possible.

Four billion years is a long time, but in the Moon's frozen geology, that ancient moment lives on - waiting for us to arrive and read its story.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.