Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: Space tethers use physics instead of fuel to move spacecraft between orbits. Multiple missions have proven the technology works, and it could soon revolutionize satellite deorbiting and deep space launches.

Imagine lifting a spacecraft to a higher orbit or slinging it toward the Moon using nothing but a very long cable and some clever physics. No rocket fuel. No exhaust plumes. Just momentum exchange and electromagnetic forces doing work that currently costs millions of dollars per mission. It sounds like science fiction, but space tether propulsion systems have already been tested in orbit, and they're getting closer to transforming how we move things around in space.

The concept is deceptively simple. A momentum exchange tether is essentially a very long cable that rotates in space, acting like a giant sling. When a spacecraft catches one end of the tether, it gets accelerated to a higher velocity, while the tether system loses energy. The beauty is that this happens without consuming any propellant at all. It's pure physics, leveraging conservation of momentum and angular momentum in ways that feel almost magical.

Meanwhile, electrodynamic tethers work on a different principle entirely. These conducting cables interact with a planet's magnetic field. When a tether moves through Earth's magnetic field, it generates electricity. Run a current through it in the opposite direction, and you generate thrust. It's like turning your spacecraft into an electric motor that uses the planet's magnetic field as its stator.

The fundamental principle behind momentum exchange tethers is conservation of angular momentum. Picture a figure skater pulling in their arms to spin faster. A rotating tether does the opposite: when it releases a payload from its tip, the payload flies off at high speed while the tether slows down. The energy doesn't disappear; it just gets transferred.

The YES2 mission demonstrated this beautifully in 2007. The European Space Agency deployed a 31.7-kilometer tether from the Foton-M3 spacecraft, the longest artificial structure ever flown in space at the time. When the tether reached its full length and released a small capsule called Fotino, U.S. Space Surveillance Network data showed the spacecraft's altitude changed by approximately 1,300 meters. That's a measurable orbital change achieved without firing a single thruster.

The YES2 mission proved that a 31.7-kilometer tether could produce a measurable 1,300-meter altitude change without any propellant - pure physics in action.

Electrodynamic tethers tap into Earth's magnetic field using Faraday's law of induction. When a conducting tether moves through the field, it generates a voltage along its length. In NASA's 1996 experiment, a 20-kilometer conducting tether generated 3,500 volts before an electric arc severed it after just five hours. That failure taught engineers crucial lessons about current management and insulation.

The physics gets more interesting when you consider that these systems can work in reverse. Instead of generating power by slowing down, you can pump power into an electrodynamic tether to speed up. The Lorentz force created by running current through the tether in Earth's magnetic field produces thrust, pushing the spacecraft to a higher orbit without expelling any mass.

Space tether concepts date back to the 1970s, but material limitations delayed practical demonstrations for decades. The technological readiness level has remained stubbornly low, hovering around TRL 4-5, because each mission encountered unexpected challenges.

NASA's Tethered Satellite System missions in the 1990s were supposed to prove the concept. TSS-1 in 1992 deployed only 260 meters of its planned 20-kilometer tether before a mechanical jam halted deployment. The mission demonstrated the principle but fell far short of its goals.

Four years later, TSS-1R tried again. This time the tether deployed to 19.7 kilometers and successfully generated power. Then disaster struck. An unexpected current surge caused an electric arc that severed the tether. The satellite drifted away, and the mission ended abruptly. Post-flight analysis revealed that electron collection along the tether created instabilities nobody had fully anticipated.

"The tether deployed to a minimum of 29.5 km, or more likely to its full length of 31.7 km, at high speed."

- Michiel Kruijff, Lead System Engineer for Delta-Utec

The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory's Tether Physics and Survivability Experiment (TiPS) took a different approach. Launched in 1996, this 6-kilometer tether was designed to study long-term survivability in the debris-filled orbital environment. It worked brilliantly for ten years before finally breaking in 2006, presumably due to micrometeoroid damage. TiPS proved that properly designed tethers can survive much longer than early pessimists predicted.

The YES2 mission in 2007 pushed the envelope further. The tether was just 0.5 millimeters in diameter, made of ultra-strong Dyneema fiber, and weighed only 5.8 kilograms despite being 31.7 kilometers long. Deployment took seven hours and involved complex dynamics: the team observed sound waves, transverse waves, and spring-mass oscillations propagating through the tether.

The mission wasn't perfect. An intermittent power failure in the optical loop detector caused the second stage to over-deploy by 1.7 kilometers, creating a shock load when the tether reached its end. But the deployment succeeded, the tether survived, and the capsule was released. Post-mission analysis from the ESA team confirmed that the tether unwound fully and achieved its momentum exchange objective.

Today, several organizations are actively developing tether systems for practical applications. The focus has shifted from pure science demonstrations to solving real operational problems, particularly orbital debris removal and satellite deorbiting.

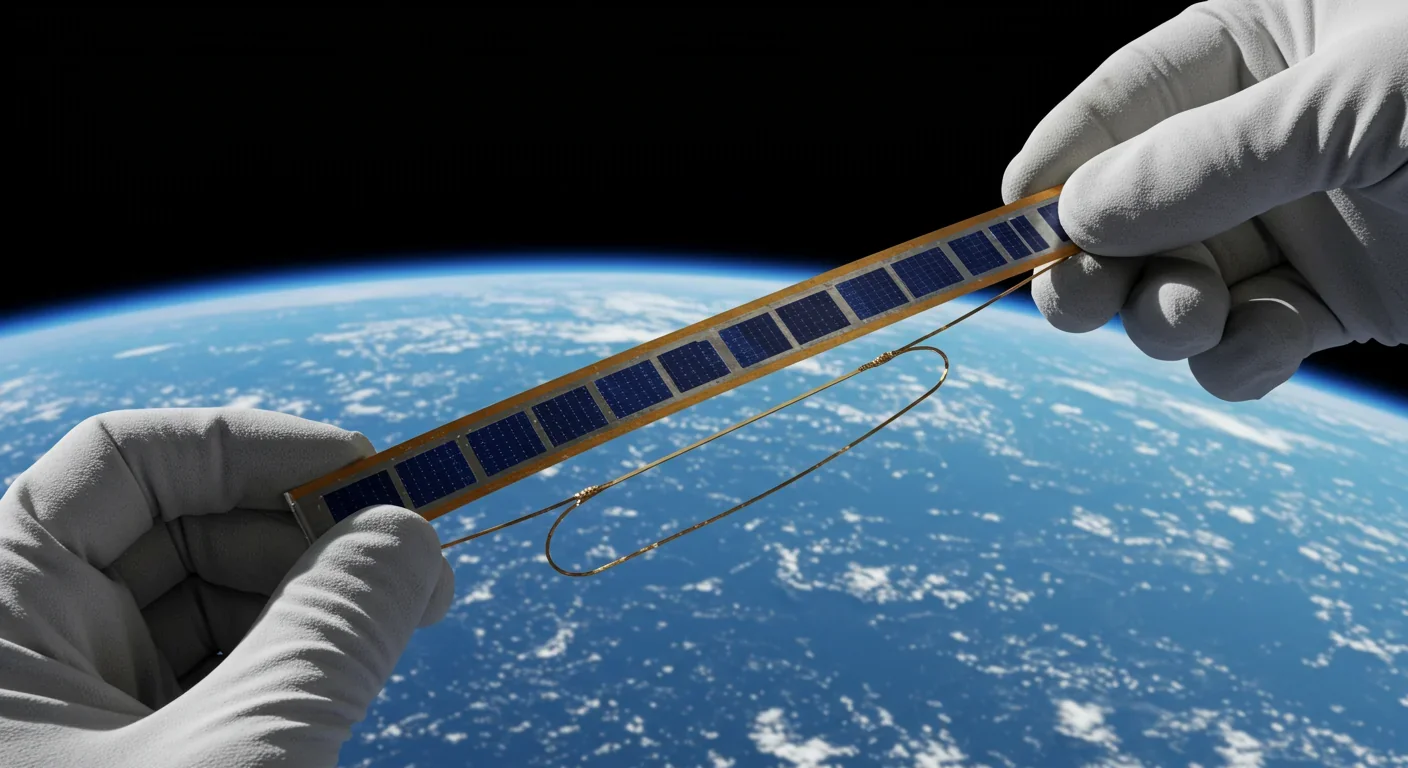

The European Innovation Council awarded 2.5 million euros in 2024 to the E.T.PACK-F initiative, which developed a prototype 12U, 24-kilogram deorbit device. The system uses an aluminum tape tether about 2 centimeters wide and 500 meters long for electrodynamic drag propulsion. The idea is simple: attach the device to a dead satellite, deploy the tether, and let electromagnetic drag slowly lower the satellite's orbit until it burns up in the atmosphere.

Researchers at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid added an interesting twist. They integrated thin-film solar cells onto one side of the tether, creating a hybrid device that generates power while producing drag. Laboratory tests showed enhanced power generation capabilities that could boost deorbit performance, potentially enabling more aggressive trajectories.

The University of Strathclyde completed a study in June examining motorized momentum-exchange tethers for Earth-Moon transfers. Unlike passive rotating tethers, these systems actively control the tether length and rotation rate, allowing them to optimize performance for each payload.

Meanwhile, researchers at the University at Buffalo applied machine learning techniques to tether-and-net capture mechanisms for active debris removal. Their work demonstrates that automated systems can reliably capture tumbling debris using tether-based technology, though nobody has deployed such a system operationally yet.

Simulation tools have also matured significantly. In October 2024, a cross-verification study compared five different electrodynamic-tether simulation codes from JAXA, Penn State, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, University of Padova, University of Michigan, and York University. The convergence of results across these independent codes suggests that engineers can now model tether behavior with enough confidence to support mission planning.

Material strength remains the fundamental constraint. A tether must be incredibly strong relative to its weight. The key metric is specific strength: tensile strength divided by density. Current high-performance materials like Zylon and M5 fiber achieve specific strengths around 3,000-5,000 kN·m/kg, giving them breaking lengths of 300-500 kilometers. That's theoretically enough for many applications.

But practical systems need safety margins. A rotating momentum exchange tether experiences dynamic loads during payload capture and release. The YES2 team documented unexpected friction during deployment, attributed to thermomechanical settling of the tether spool. Sound waves and transverse waves propagated through the tether, creating complex stress patterns.

Micrometeoroid and orbital debris impacts pose another threat. The TiPS mission survived a decade, but its eventual failure demonstrated that even small impacts can sever a thin tether. The Hoytether design offers a solution: instead of a single strand, it uses a net-like structure that distributes strain across multiple strands. If one strand breaks, the load automatically redistributes to the others. Theoretical lifetimes extend to decades with such designs.

Electrodynamic tethers face additional challenges. Pendular motion instability can grow over weeks, degrading performance unless actively controlled. Current modulation can counteract this vibration growth, but it requires sophisticated control systems and real-time monitoring.

Electron collection along a bare conducting tether follows Orbital Motion Limited theory when the tether radius is smaller than the plasma Debye length. For wider tethers, collection efficiency rises significantly, but so does drag. Engineers must balance electrical performance against mechanical stress.

Material science is the bottleneck: today's best fibers can theoretically support 300-500 kilometer tethers, but practical systems need safety margins against dynamic loads, micrometeoroids, and deployment stresses.

The NASA ProSEDS mission was supposed to demonstrate a 5-kilometer electrodynamic tether for deorbiting spacecraft, achieving an electromotive force of 35-250 volts per kilometer. The mission was canceled before launch, leaving a gap in demonstrated technology.

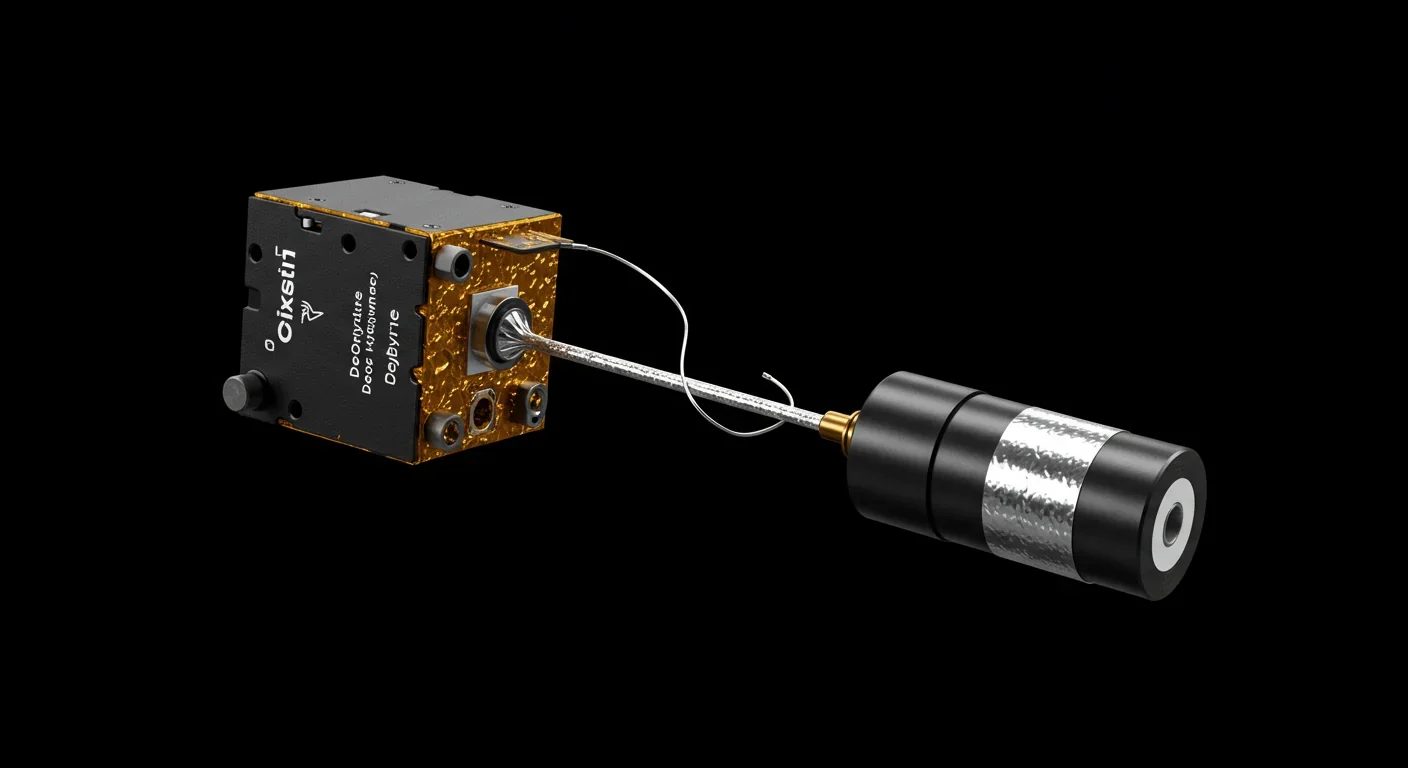

Deployment mechanics remain tricky. The YES2 team used a barberpole friction brake with stepper motor control and closed-loop sensor feedback. This system worked well enough to stop deployment at precise lengths, but the intermittent power failure that caused over-deployment shows how sensitive these systems are to minor faults.

Current processing reliability is critical. The YES2 mission analyst noted that the braking and control mechanism didn't work as expected because of a fault in the flight computer's real-time processing of sensor data. Future missions will need redundant control loops to prevent similar failures.

The most immediate application is satellite deorbiting. Regulations now require satellites to deorbit within 25 years of mission end. Chemical propulsion systems to accomplish this add mass and complexity. An electrodynamic tether offers a simpler alternative: just deploy the tether and let electromagnetic drag do the work over several months.

Japan's KITE experiment and other international initiatives have explored using tethers for debris capture. The concept involves approaching a dead satellite or debris fragment, attaching a tether, and using Lorentz forces to slow it down for controlled re-entry. Nobody has successfully captured an uncooperative target yet, but the underlying physics works.

Momentum exchange tethers could serve as reusable upper stages. Picture a rotating tether in low Earth orbit. A spacecraft launched from Earth docks with the lower end of the tether, rides up to the tip as the tether rotates, then releases at the optimal moment. The spacecraft gains enough velocity to reach a higher orbit or even escape Earth's gravity entirely, depending on the tether's tip speed.

Practical tip speeds for rotating tethers are cited at 1-3 kilometers per second, limited by material strength, taper ratio, and safety factors. That's enough to provide significant delta-v without propellant. The momentum exchange concept could dramatically reduce the fuel mass required for interplanetary missions.

The Bolo concept takes this further, envisioning a network of rotating tethers at different altitudes and inclinations. A spacecraft could hop from one tether to the next, gradually building up velocity without ever firing its engines except for minor course corrections.

"The deployer was designed with a broad engineered range of near-term tether applications in mind and is an inherently reliable concept, if properly controlled."

- Michiel Kruijff, YES2 Mission Lead Engineer

Unfortunately, an Earth-to-orbit rotovator cannot be built from currently available materials. The thickness and mass required to handle the loads would be economically impractical. The gravity well is simply too deep, and the velocity change too large.

But for lunar applications, the picture brightens considerably. The Moon's lower gravity and lack of atmosphere make tether systems much more feasible. A lunar space elevator could use materials available today, such as Kevlar, M5 fiber, or Spectra 2000, to support payloads from the lunar surface to the L1 Lagrange point.

An M5 fiber ribbon just 30 millimeters wide and 0.023 millimeters thick could support 2,000 kilograms on the lunar surface. It could hold 100 cargo vehicles, each with a mass of 580 kilograms, evenly spaced along the elevator's length. A 540-kilogram robotic climbing vehicle powered by solar or beamed energy would require only 10 kilowatts at the surface when moving at 15 meters per second, dropping to less than 100 watts near the L1 point.

The counterweight requirements are substantial: about 1,000 kilograms positioned 26,000 kilometers from Earth for the L1 point, or 120,000 kilometers for the L2 point. But these are solvable engineering challenges, not fundamental physics barriers. A lunar elevator could reduce launch costs for payloads to the Moon by factors similar to the propellant savings it provides.

For Earth-Moon transfers, momentum exchange tethers offer another possibility. Instead of a static elevator, a motorized tether could catch payloads from low Earth orbit and sling them toward the Moon, then catch returning payloads from lunar orbit and bring them back to Earth. The system would need regular orbit maintenance, but it wouldn't consume propellant for each transfer.

Chemical rockets achieve high thrust but consume propellant at a furious rate. Specific impulse for chemical systems tops out around 450 seconds. Ion drives offer much better efficiency, with specific impulses exceeding 3,000 seconds, but produce tiny thrust and require substantial power.

Tether systems offer a third option. Momentum exchange tethers produce no thrust directly; instead, they exchange momentum with each payload. The tether system slowly loses energy and altitude with each upward transfer, requiring periodic reboost. But that reboost can use efficient ion drives or even solar electric propulsion, since there's no hurry.

Electrodynamic tethers produce continuous low thrust, similar to ion drives, but without consuming propellant. The thrust magnitude depends on tether length, current, and the local magnetic field strength. The E.T.PACK-F device with its 500-meter tether generates enough drag to deorbit a satellite over several months.

The environmental impact differs dramatically. Chemical rockets produce exhaust plumes that can contaminate sensitive instruments and deposit particles in orbit. Ion drives expel propellant, though in much smaller quantities. Tether systems produce no exhaust at all. The only environmental concern is the tether itself becoming debris if it breaks, which is why modern designs emphasize deorbit capability.

Cost comparisons are harder because tether systems haven't been deployed commercially. The E.T.PACK-F 12U deorbit device weighs 24 kilograms, comparable to chemical deorbit systems but potentially more reliable since it has no moving parts except the deployment mechanism.

Unlike chemical rockets or ion drives, tether systems produce zero exhaust - the only environmental concern is the tether itself becoming debris if severed, which is why modern designs include deorbit capability.

For a reusable momentum exchange system, the economics become compelling. Launch the tether facility once, and it can transfer hundreds or thousands of payloads over its operational lifetime. Each transfer costs essentially nothing except the energy required for periodic orbit maintenance. Mission costs could drop dramatically, potentially opening up applications that are currently economically impractical.

Several factors need to align for tether propulsion to transition from experimental demonstrations to operational systems. Material science continues advancing. Carbon nanotubes and graphene theoretically offer specific strengths over 100 times that of steel, though manufacturing long, defect-free fibers remains challenging.

Automated deployment and control systems need further refinement. The YES2 mission showed that closed-loop sensor feedback works, but reliability must improve. Machine learning approaches, like those being developed at the University at Buffalo, could enable more robust autonomous operation.

Standardization would help. If tether interfaces became standardized, satellites could be designed from the start to work with tether systems. A spacecraft heading to geostationary orbit could launch with minimal propellant, knowing it will catch a ride on a momentum exchange tether from low Earth orbit.

Regulatory frameworks need development. Who owns orbital momentum? If a tether facility provides delta-v by transferring momentum, it gradually loses altitude. Should payload customers compensate for that? How should orbital slots be allocated to rotating tether facilities? These aren't just technical questions; they require international coordination.

Funding remains uncertain. The European Innovation Council and ESA have invested millions in tether development, but that's modest compared to traditional propulsion programs. Private companies have mostly stayed on the sidelines, waiting for government agencies to retire the technical risks.

Demonstration missions could accelerate adoption. A successful electrodynamic deorbit of a real satellite would prove the technology more convincingly than any simulation. A momentum exchange tether that successfully transfers a payload from low Earth orbit to geostationary transfer orbit would turn heads throughout the industry.

The physics of space tethers is sound. Multiple missions have demonstrated that long tethers can be deployed, that they survive in the orbital environment for years, and that they produce measurable thrust or momentum exchange. The technology works.

What's missing is the bridge from laboratory demonstration to operational system. That bridge requires engineering refinement, regulatory support, and probably a few more failed missions to learn the last hard lessons. The TSS-1R arc that destroyed a 20-kilometer tether taught engineers about current management. The YES2 over-deployment revealed the importance of reliable sensor processing. Each failure moved the technology forward.

The question isn't whether tether propulsion will work. It already works. The question is when it will become economically and operationally compelling enough that satellite operators choose tethers over chemical rockets or ion drives. Given the growing pressure to clean up orbital debris, the environmental advantages of propellant-free deorbiting might tip the scales sooner than the pure cost analysis suggests.

Within the next decade, you'll likely see the first commercial deorbit tethers deployed on operational satellites. Within two decades, momentum exchange facilities might be transferring payloads between Earth orbits routinely. And someday, perhaps within your lifetime, a rotating tether might catch your spacecraft in low Earth orbit and sling you toward Mars without burning a single drop of fuel.

The revolution won't announce itself with dramatic rocket launches. It will arrive quietly, as a thin fiber unreeling in the darkness, turning orbital mechanics into something closer to engineering than to magic.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.