Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: After 40 years since Voyager 2's flybys, NASA is planning a flagship Uranus mission for the 2030s while China proposes a Neptune orbiter, marking humanity's return to the ice giants with advanced technology that could unlock mysteries about magnetic fields, exotic interiors, and potentially habitable moons.

By 2040, the last pixels transmitted from Voyager 2's Neptune encounter in 1989 will be more than half a century old. Think about that. We've spent more time not visiting these planets than the entire Space Age before Voyager launched. But that drought is ending, and what's coming could fundamentally reshape how we understand not just our solar system, but the thousands of ice giant exoplanets we've discovered orbiting distant stars.

The 2023 Planetary Science Decadal Survey didn't just recommend a Uranus Orbiter and Probe as a priority - it ranked it as the top flagship mission for the next decade. NASA's already begun early planning for a launch window in the early 2030s, targeting arrival around 2045. Meanwhile, Chinese scientists have proposed a 2033 Neptune orbiter, potentially creating the first international race to the outer solar system since the Cold War.

This isn't just about filling gaps in our planetary photo album. Ice giants represent 50-100 times more common planetary architecture in the galaxy than Jupiter-sized gas giants. Understanding Uranus and Neptune means understanding the most typical planetary outcome in the universe - and we've barely scratched the surface.

When Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989, it spent just hours in close proximity to each world. Imagine trying to understand Earth's climate, geology, and potential for life from a single afternoon's observation while racing past at 40,000 mph. That's essentially where ice giant science has been stuck since shoulder pads were fashionable.

The data Voyager returned was revolutionary - discovering Neptune's Great Dark Spot, revealing Uranus's bizarrely tilted magnetic field, finding six new moons around Neptune including the geologically active Triton. But every answer spawned ten new questions that only an orbiter could address.

Consider what we've learned about other planets through dedicated orbiters versus flybys. Cassini spent 13 years at Saturn and transformed our understanding of ring dynamics, moon geology, and atmospheric chemistry. The Mars orbiters have rewritten planetary science textbooks. Ice giants deserve the same treatment, yet they've received none of it.

The timing of that 40-year gap wasn't arbitrary - it was economic and political. Flagship planetary missions cost billions and require decades of planning. After Voyager's grand tour, NASA's focus shifted to Mars, the outer planet moons, and eventually the Moon again. The ice giants, 1.8 to 2.8 billion miles away, simply weren't priorities when budgets tightened and attention spans shortened.

The term "ice giant" itself reveals a fundamental misunderstanding that persisted for decades. These aren't scaled-up versions of Jupiter and Saturn with hydrogen-helium envelopes. They're fundamentally different beasts with exotic interiors dominated by water, methane, and ammonia ices compressed into states that don't exist naturally on Earth.

Recent computer simulations suggest these planetary interiors spontaneously separate into distinct layers - water-rich above, carbon-rich below - under the extreme pressures and temperatures deep inside ice giants. This layered structure could explain one of the most perplexing mysteries Voyager uncovered: the weirdly tilted and offset magnetic fields.

Uranus's magnetic field is tilted 59 degrees from its rotation axis and doesn't even pass through the planet's center. Neptune's is similarly askew. Every other planet's magnetic field roughly aligns with its rotation axis because they're generated by convecting fluids in the core. Ice giants break that rule, suggesting something fundamentally different about their internal structure and dynamics.

Understanding ice giants isn't academic - it's the key to interpreting the most common type of exoplanet we've discovered orbiting other stars.

The leading theory now involves superionic ice - a bizarre state of matter where oxygen atoms lock into a crystalline lattice while hydrogen ions flow freely like a liquid. This semi-solid, semi-liquid state could conduct electricity differently than conventional convecting fluids, generating magnetic fields with unusual geometries. But we can't confirm this without detailed measurements over years, tracking how these fields fluctuate and interact with the solar wind.

Then there's Uranus's extreme axial tilt - 98 degrees, meaning it essentially rolls through its orbit on its side. This creates the most extreme seasonal variations in the solar system, with each pole experiencing 42 years of continuous sunlight followed by 42 years of darkness. How does an atmosphere respond to that? We have models, but Voyager only saw one brief moment of one season at one planet.

NASA's Uranus Orbiter and Probe concept has evolved significantly since first proposed in 2011. The current design calls for a 7,235 kg spacecraft powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators - essentially nuclear batteries using plutonium-238 decay. Solar panels won't work at Uranus's distance where sunlight is 1/400th as intense as at Earth.

The mission architecture involves a 13-year cruise using gravity assists from Earth, Venus, and Jupiter to reach Uranus around 2045. Once there, the orbiter will spend at least four years studying the planet, its 27 known moons, and 13 known rings from multiple orbital inclinations. The atmospheric probe will separate before orbital insertion, plunging into Uranus's clouds to directly measure composition, temperature, pressure, and wind speeds as it descends.

The estimated cost sits around $4.2 billion in 2025 dollars - expensive, but comparable to other flagship missions like Europa Clipper or Mars Sample Return. For that investment, scientists get answers to questions that have lingered for 40 years: What drives the powerful winds on these seemingly placid worlds? How deep do the atmospheres extend before transitioning to the exotic icy interiors? What's the chemical makeup, and does it match formation models?

"The 2023 Decadal Survey identified the Uranus mission as the highest priority for the next decade because it addresses fundamental questions about planetary formation, interior dynamics, and magnetospheric physics that we simply cannot answer from Earth."

- Planetary Science Decadal Survey

Neptune missions remain conceptual but equally compelling. The Neptune Odyssey proposal envisions an orbiter conducting at least 46 flybys of Triton over a four-year primary mission. Triton itself is a scientific jackpot - a captured Kuiper Belt object with active cryovolcanism, a thin nitrogen atmosphere, and possibly a subsurface ocean. At temperatures around -235°C, it's the coldest known object in the solar system, yet it's geologically young with surface ages estimated at just 10-100 million years.

China's proposed 2033 Neptune mission could beat NASA there, arriving as early as 2045 with a combination orbiter-probe architecture similar to the Uranus concept. The mission would use a gravity assist from Triton after orbital insertion to adjust its trajectory - a complex maneuver requiring precise navigation but offering unprecedented access to both Neptune and its most interesting moon.

Getting multi-ton spacecraft to the ice giants requires pushing propulsion technology to its limits. Traditional chemical rockets barely suffice, requiring complex gravity assist trajectories that add years to transit times and limit launch windows to narrow periods when planets align favorably.

Nuclear propulsion technologies could change that calculus. Nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP) engines, which use nuclear reactors to superheat propellant, offer specific impulse around 850 seconds - roughly double that of conventional chemical rockets. A 13,000-pound-thrust NTP engine could cut several years off transit times to Uranus or Neptune and eliminate the need for gravity assists, opening launch windows and enabling more flexible mission profiles.

Even more speculative are nuclear electric propulsion systems and concepts like SpaceX's Starship as a Uranus mission platform. Starship's enormous payload capacity could enable missions carrying far more instruments, multiple probes, or even sample return capabilities. Using aerocapture at Uranus - flying through the upper atmosphere to shed velocity rather than burning fuel - Starship could potentially reach the ice giants in just 6-8.5 years depending on trajectory.

Power generation at such distances presents challenges no Mars or asteroid mission faces. The ice giant missions will rely on radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which convert heat from radioactive decay directly into electricity. Recent advances like subcritical RTGs, which couple alpha decay with neutron sources, can boost efficiency by 10% and reduce the mass of plutonium-238 required - critical given that this isotope is in limited supply.

The spacecraft must also survive 13+ years in the radiation environment of interplanetary space and the ice giants' magnetospheres, operate autonomously with communication delays exceeding four hours, and maintain precision pointing for instruments and communications despite never being refueled or serviced.

The ice giants represent a new arena for space exploration where international dynamics differ from the Moon or Mars. No strategic resources exist to claim, no immediate commercial applications beckon. This is pure science, which historically has enabled collaboration even between geopolitical rivals.

China's Neptune proposal explicitly invites international participation, suggesting opportunities for shared instruments or data. European Space Agency missions have consistently partnered with NASA on outer solar system exploration. There's precedent for cooperation extending beyond traditional allies when the science justifies it.

Yet competition has benefits too. When the Soviet Union and United States raced to the Moon, both programs advanced faster than either might have alone. If China launches to Neptune in 2033 and NASA reaches Uranus in the early 2030s, the 2040s could see simultaneous ice giant missions returning data, enabling comparative planetology in real-time and motivating continued funding through high-profile discoveries.

The technology developed for these missions - advanced nuclear propulsion, autonomous navigation, extreme-environment instrumentation - will enable exploration throughout the outer solar system and potentially to nearby interstellar space. Gravity assist techniques pioneered for Voyager and refined for these missions make reaching distant destinations feasible within human career timescales rather than generations.

While the ice giants themselves justify missions, their moons might ultimately prove more scientifically valuable. Triton's active geology despite frigid surface temperatures suggests internal heat sources - tidal heating from its unusual retrograde orbit around Neptune, perhaps combined with radiogenic heating. Where there's heat and potential liquid water, astrobiology gets interested.

Triton's atmosphere, though tenuous at just 1.4 pascals pressure, varies mysteriously. Voyager measured it in 1989; ground-based observations in 2010 suggested it had tripled; by 2017 it had returned to original levels. Something is driving atmospheric changes on decadal timescales, possibly seasonal, possibly tied to internal activity. An orbiter conducting dozens of Triton flybys would track these variations and potentially witness active cryovolcanic eruptions.

Uranus's moon Miranda presents different mysteries. Its surface displays the most dramatic geological contrasts in the solar system - ancient cratered terrain adjacent to younger grooved regions suggesting massive resurfacing events. The leading theory involves tidal heating during temporary orbital resonances with other Uranian moons, creating periods of geological activity separated by dormant phases. Voyager saw one frozen moment; an orbiter would reveal whether Miranda still retains internal heat or has fully frozen solid.

The smaller irregular moons, the faint ring systems, the interactions between planetary magnetospheres and moon environments - all represent uncharted scientific territory. Every major planetary mission has discovered things that couldn't be predicted from Earth-based observations. Ice giant missions will certainly do the same.

The comparative planetology enabled by having detailed data from ice giants, gas giants, and terrestrial planets will complete our understanding of planetary system formation and evolution.

The explosion of exoplanet discoveries over the past three decades revealed that our solar system is unusual. Hot Jupiters, super-Earths, and ice giant analogs vastly outnumber solar system lookalikes. Ice giants are 50-100 times more common than Jupiter-sized planets around other stars, making Uranus and Neptune the closest accessible examples of the galaxy's most typical large planets.

When we detect an exoplanet's mass, radius, and atmospheric composition via transit spectroscopy, we interpret that data through models calibrated against solar system planets. But our ice giant models rest on limited Voyager data and assumptions that may not hold. If Uranus and Neptune have layered interiors, superionic ice mantles, or unexpected atmospheric chemistry, our interpretations of thousands of exoplanets might need revision.

The ice giant missions will provide ground truth for testing planetary formation theories. Did Uranus and Neptune form where they orbit now, or did they migrate from closer to the Sun? Their compositions and isotope ratios hold answers. Do ice giants commonly have moons, rings, and complex magnetospheres? Understanding the mechanisms that generate these features at Uranus and Neptune tells us what to expect - and search for - around distant ice giants we'll never visit.

The window for launching a Uranus mission opens in the early 2030s when planetary alignments enable efficient gravity assist trajectories. Miss that window, and the next opportunity might not come for over a decade. This creates urgency - the mission must move from concept to flight-ready hardware within roughly a decade, a challenging timeline for flagship-class missions.

Budget uncertainties always threaten ambitious science missions. At $4.2 billion, the Uranus Orbiter and Probe competes with Mars missions, lunar exploration, telescope programs, and Earth science for limited NASA funding. Past flagship missions have experienced delays and cost overruns that complicated schedules and strained budgets. Maintaining political and public support through multiple administrations requires sustained advocacy from the planetary science community.

Technical risks abound in any mission to the outer solar system. The plutonium-238 supply for RTGs remains constrained despite recent production restarts. Developing an atmospheric probe that can survive entry heating and function in the extreme cold of Uranus's upper atmosphere while transmitting data back to the orbiter pushes engineering limits. The 13-year cruise means components must remain functional far longer than typical spacecraft lifetimes, with no possibility of repair or software patches if critical systems fail.

Yet these challenges are precisely why these missions matter. The difficult things teach us more than the easy things. Mars is comparatively accessible, but ice giants force innovation in propulsion, power, autonomy, and instrument design. Technologies developed for these missions will enable future exploration of ocean worlds, Kuiper Belt objects, and eventually interstellar space.

"Every time we've sent a spacecraft somewhere new in the solar system, we've been surprised. The ice giants will be no different - except we've waited 40 years for those surprises."

- Planetary Scientists

Unlike Mars missions that build toward human exploration, or lunar programs with geopolitical significance, ice giant missions offer purely scientific returns. There's no pathway to colonize Uranus, no resources to mine, no strategic advantage to claim. The value is entirely in expanding human knowledge and satisfying curiosity about how planetary systems work.

That's actually a strength rather than a weakness. The most enduring scientific achievements - mapping the cosmos, sequencing the human genome, discovering quantum mechanics - weren't justified by immediate practical applications. They were driven by the fundamental human need to understand our universe. Ice giant missions continue that tradition, asking questions for their own sake.

The spectacular images alone will captivate public imagination. Voyager's grainy Neptune photos, despite their low resolution, remain iconic. Modern cameras and communications will return 4K video of storms larger than Earth, close-ups of alien moons, and views of the solar system's edge that make the planets feel real rather than abstract points of light.

Educational impacts ripple across generations. Students who follow these missions in grade school become the scientists, engineers, and informed citizens of the 2050s and beyond. The technical challenges inspire innovation in fields far removed from space exploration. The international cooperation demonstrates that humanity can work together toward shared goals even when immediate national interests don't align.

Imagine watching the live feed in 2045 or 2046 as a spacecraft approaches Uranus for the first time in 60 years. The planet resolves from a blue-green dot into a disc with visible cloud features and the dark line of rings crossing it. Uranus's 13 rings come into focus, narrow and dark compared to Saturn's brilliant ones, shepherded by small moons whose names we know but whose surfaces we've never seen.

The atmospheric probe separates, beginning its one-way journey into Uranus's clouds. For roughly 37 minutes it transmits data as it falls, measuring temperatures, pressures, wind speeds, and chemical compositions directly rather than inferring them from distant observations. The winds might howl at hundreds of miles per hour despite the seemingly placid appearance. The chemistry might reveal unexpected compounds that alter formation theories.

Then the orbiter fires its engines, slowing into orbit, beginning years of systematic observation. Every few weeks it passes close to a different moon, mapping surfaces and measuring masses. It flies through the magnetosphere at various angles and distances, tracing the field lines and understanding how this bizarre offset magnetic field shapes the space environment around Uranus.

The data streams back to Earth at the speed of light, taking over 2.5 hours to cross the gulf between worlds. Scientists around the world analyze it in near-real-time, posting findings, debating interpretations, rewriting textbooks as discoveries accumulate. New PhD theses emerge from single datasets. Entire careers will be built on understanding what these missions reveal.

The scientists who planned the Voyager missions in the 1960s and 70s knew they wouldn't see follow-up missions to Uranus and Neptune in their careers. They hoped the next generation would carry that torch forward. But that next generation faced budget cuts, shifting priorities, and the reality that space exploration moves in decades, not years.

Now we're the generation that can end the 40-year drought. The technology exists. The scientific justification is overwhelming. The planetary alignments are cooperating. What's required is the collective will to fund and support missions that won't complete until people born today are in their 20s.

That long timeline isn't a bug - it's a feature. Civilization-scale projects that span decades remind us we're part of something larger than quarterly earnings reports or election cycles. They connect us to both our exploration heritage and our descendants who will benefit from the knowledge we've gathered.

The ice giants have waited in the outer darkness for 4.6 billion years. They'll wait a few billion more whether we visit them or not. But we won't wait. We're curious, ambitious, and capable of reaching worlds so distant that sunlight arrives as a faint whisper. The 2030s will mark humanity's return to the ice giants not because it's easy, but because understanding our place in the universe requires it.

The spacecraft are being designed. The scientists are planning investigations. The launch windows are opening. What happens next depends on whether we value knowing over remaining ignorant, whether we invest in questions whose answers won't arrive for decades, whether we believe that exploring the cosmos matters even when it doesn't pay dividends.

Every great exploration began with someone deciding the unknown was worth pursuing. The ice giants represent one of the last frontiers in our solar system, and we finally have the means to explore them properly. The only question is whether we'll seize this moment or let another generation pass while Neptune and Uranus remain as mysterious as they were when Voyager raced past them 40 years ago.

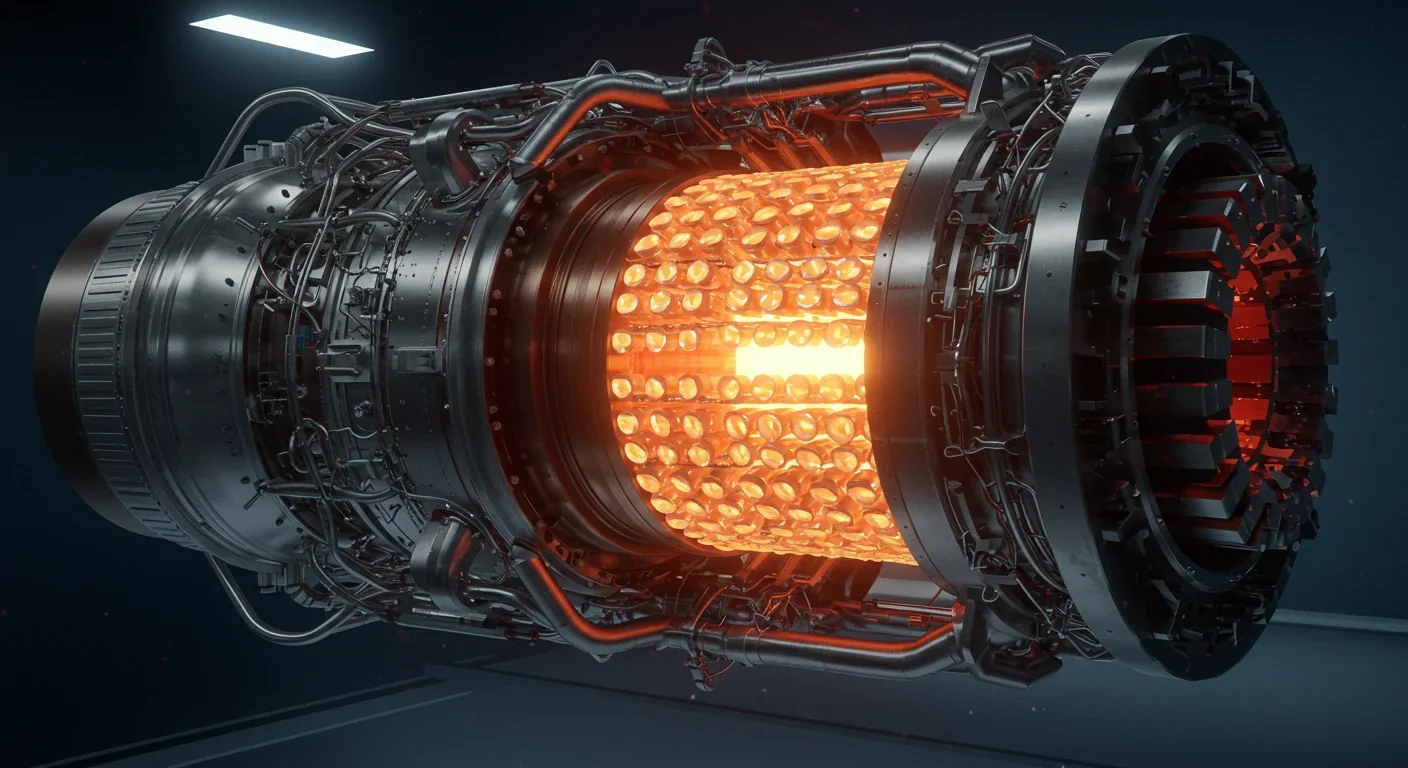

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.