Rotating Detonation Engines: 25% More Efficient Rockets

TL;DR: Japanese and American researchers have achieved breakthrough 15% efficiency in laser power beaming through atmosphere, making space elevator climbers technically feasible for the first time with targeted 2050 deployment.

In September 2025, a team from NTT and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries achieved something that science fiction writers have dreamed about for decades: they successfully transmitted 1,000 watts of laser power over a full kilometer through turbulent air, converting it into usable electricity with world-record efficiency. This breakthrough wasn't just another laboratory curiosity. It represented the first real proof that we could power vehicles climbing a tether stretching 100,000 kilometers into space, transforming humanity's relationship with orbit forever.

The concept sounds almost absurdly ambitious: build a cable from Earth to geostationary orbit, then send laser-powered robotic climbers up and down like elevators in the world's tallest building. Yet this wild idea has attracted serious investment from NASA, DARPA, and major corporations like Obayashi Corporation, which still maintains its goal of operational space elevators by 2050. The reason for this enthusiasm becomes clear when you consider the economics. Current rocket launches cost between $2,000 and $10,000 per kilogram. Space elevators could reduce that to $100 or less.

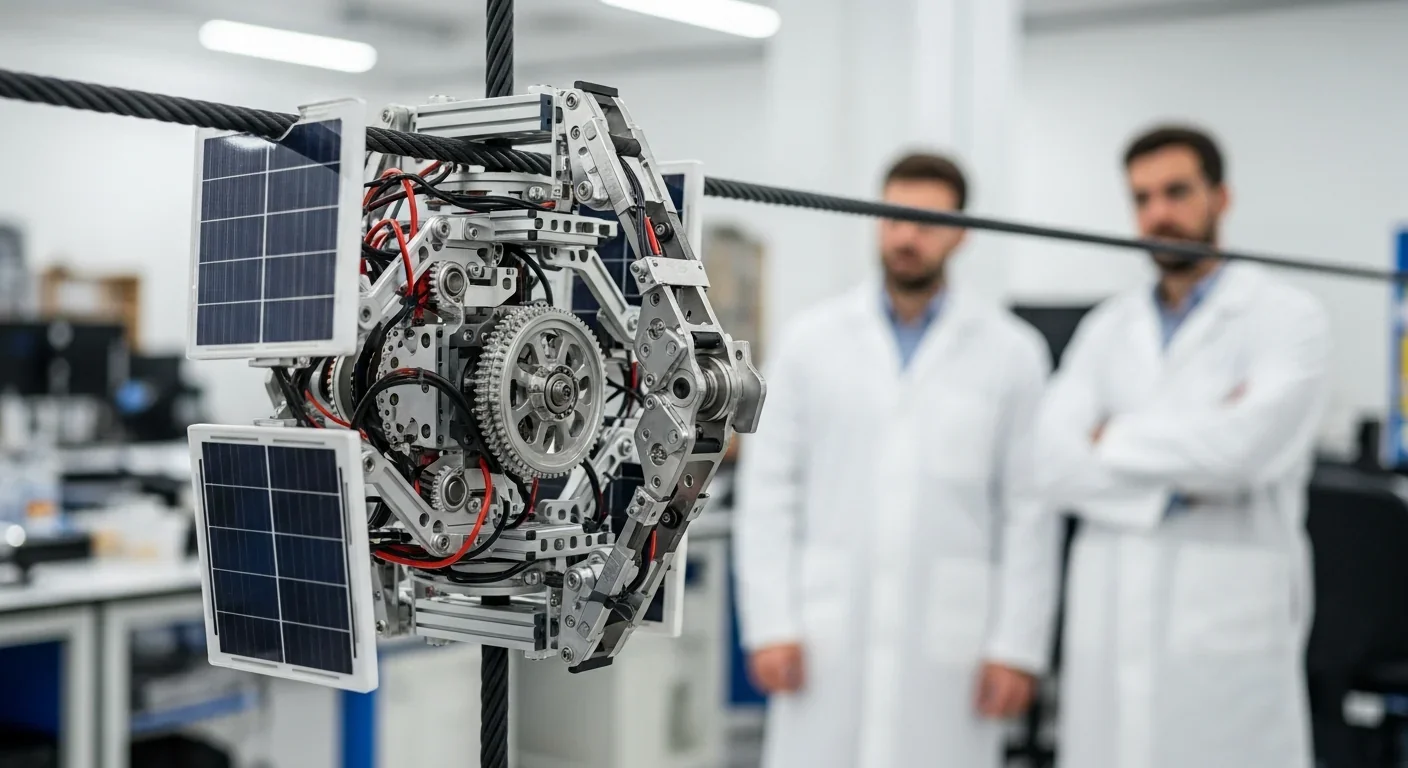

The heart of any space elevator system lies not in the tether itself, but in the vehicles that would climb it. These aren't your typical elevators with cables and counterweights. Instead, engineers envision autonomous robotic climbers powered by invisible beams of infrared light shot from ground stations or orbital platforms. The recent achievement by NTT and Mitsubishi proves this isn't fantasy anymore.

Their outdoor experiment demonstrated 15% efficiency in converting laser light to electricity after traveling through a kilometer of turbulent atmosphere. That might not sound impressive compared to the 40% efficiency of solar panels in space, but it represents a massive leap forward. Previous attempts struggled to achieve even 5% efficiency once atmospheric interference entered the equation. The key breakthrough came from combining diffractive optical elements to shape the beam with specialized homogenizers that spread out hot spots caused by air turbulence.

PowerLight Technologies, formerly known as LaserMotive, has pushed these boundaries even further. In 2024, they demonstrated wireless power transmission over five miles, though at lower power levels. Their approach uses adaptive optics borrowed from astronomy to compensate for atmospheric distortion in real-time, similar to how ground-based telescopes correct for the twinkling of stars.

The numbers tell a compelling story. To lift a 20-ton climber carrying cargo at reasonable speeds, engineers calculate you'd need between 2 and 14 megawatts of power, depending on the climbing velocity and efficiency of the system. With current 15% transmission efficiency and 50% efficient motors, that means ground stations would need to generate between 25 and 180 megawatts of laser power. That's enormous but not impossible - modern industrial lasers already operate in the multi-megawatt range for applications like steel cutting and welding.

A 15% efficiency rate in laser power transmission through turbulent atmosphere represents a threefold improvement over previous attempts, making space elevator climbers technically feasible for the first time.

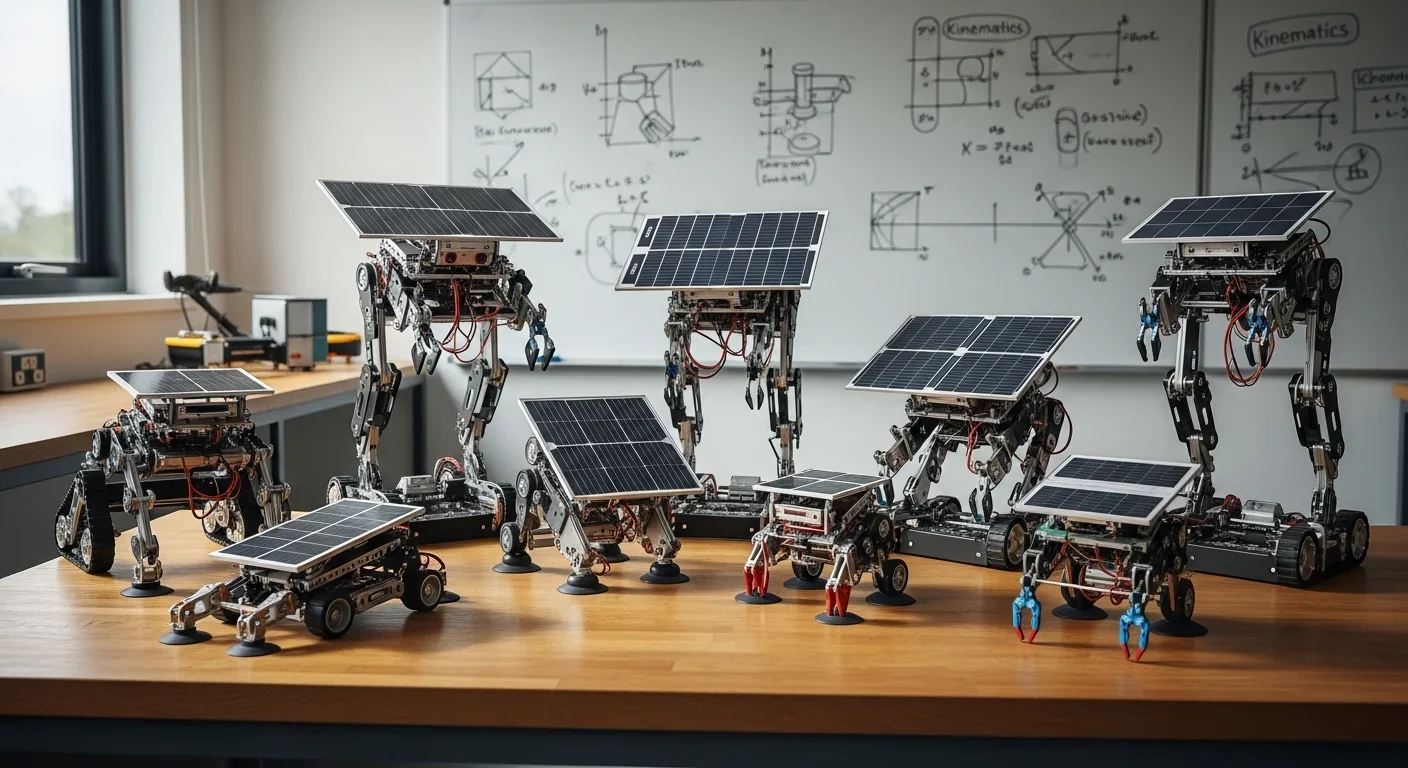

The path to practical laser-powered climbers has been paved by a series of increasingly ambitious competitions. NASA's Centennial Challenges program kicked things off in 2005 with the Space Elevator Games, offering $2 million in prizes for teams that could build functioning climber prototypes. The early years saw plenty of failures. Teams struggled with everything from basic traction problems to catastrophic power system failures that sent expensive prototypes crashing to the ground.

The breakthrough came in 2009 when LaserMotive's climber successfully ascended a 900-meter cable suspended from a helicopter, powered entirely by ground-based lasers. Their climber reached speeds of 3.9 meters per second, fast enough to win the $900,000 first prize. The victory proved that laser propulsion wasn't just theoretically possible but practically achievable with existing technology.

What made LaserMotive's design revolutionary wasn't just the power system. They pioneered a modular approach where multiple small photovoltaic receivers worked in parallel, providing redundancy if any single receiver failed. Their climber also featured intelligent tracking systems that kept the receivers aligned with the laser beam even as wind caused the tether to sway. These innovations became standard features in all subsequent designs.

European teams have taken different approaches. The Munich University team WARR developed climbers that use multiple gripping mechanisms inspired by gecko feet, distributing the load across the tether to prevent wear. Meanwhile, Japanese researchers at JAXA have focused on ultra-lightweight designs using carbon fiber composites that weigh just 20 kilograms but can carry 100-kilogram payloads.

The most recent competition winner, Star Catcher Industries, achieved a remarkable feat in 2024. Their system transmitted power wirelessly to a moving aerial platform, demonstrating that they could track and power a climber even as it moved at high speed. This dynamic targeting capability is essential for a real space elevator, where climbers would need continuous power during their week-long journey to orbit.

Building a laser-powered climber for a real space elevator presents challenges that make current prototypes look like toys. The vehicle must survive temperature swings from +50°C at ground level to -270°C in space, radiation levels that would fry normal electronics, and debris impacts at speeds of several kilometers per second. Engineers have developed fascinating solutions to each of these problems.

For thermal management, proposed designs use a combination of variable-emissivity coatings and heat pipes filled with ammonia. These systems can reject excess heat in the lower atmosphere while conserving it in the cold of space. Recent research from DARPA suggests that metamaterial-based thermal management systems could improve efficiency by 30%, crucial for maintaining optimal operating temperatures for the photovoltaic cells.

The power reception system represents perhaps the greatest engineering challenge. Current designs call for photovoltaic arrays covering 100 to 200 square meters, using multi-junction gallium arsenide cells that can achieve 40% efficiency under laser illumination. These cells must be protected by transparent armor capable of surviving micrometeorite impacts while still allowing 95% light transmission. Adaptive optics systems borrowed from astronomy would continuously adjust the receiver alignment to compensate for tether oscillations that could exceed 10 kilometers at altitude.

"The integration of adaptive optics with power beaming represents a convergence of technologies that makes the impossible merely difficult."

- Dr. Richard Fork, DARPA Optical Power Program

Safety systems require multiple levels of redundancy. Each climber would carry emergency batteries sufficient for controlled descent if laser power fails. Proposed designs include electromagnetic brakes that could grip the carbon nanotube tether without damaging its surface, arresting a fall within 100 meters. Some concepts even incorporate small rocket thrusters for emergency station-keeping if the climber becomes detached from the tether entirely.

The control systems present unique challenges too. With round-trip communication delays of up to 0.5 seconds to geostationary orbit, climbers must operate with significant autonomy. Machine learning algorithms trained on millions of simulated climbing scenarios would handle routine decisions like speed adjustments and obstacle avoidance. Human operators would only intervene for major trajectory changes or emergency situations.

While American and European efforts have focused on competitions and prototypes, Japan has taken a more systematic approach to space elevator development. Obayashi Corporation's 2050 timeline isn't just corporate optimism - it's backed by a detailed development roadmap and substantial government support.

The Japanese approach emphasizes incremental testing. They've already conducted experiments with miniature climbers on 10-kilometer tethers suspended from high-altitude balloons. These tests revealed unexpected challenges like ice formation on the tether at certain altitudes and electromagnetic interference from the ionosphere affecting power transmission. Each discovery feeds into refined designs for the next generation of prototypes.

Japanese researchers have also pioneered dual-use technologies that generate revenue while advancing space elevator development. Their wireless power transmission research has applications in disaster relief, providing emergency power to isolated areas after earthquakes or tsunamis. The carbon nanotube manufacturing techniques developed for tether production have found uses in everything from bulletproof vests to next-generation batteries.

The economic model developed by Japanese planners assumes a construction cost of $100 billion spread over 20 years, with the system becoming profitable after transporting 3,000 tons of cargo to orbit. They envision not just one climber but a continuous stream of vehicles, with one departing every day once the system reaches full capacity. At peak operation, a single space elevator could move more mass to orbit annually than all current rocket launches combined.

Cultural factors play a role too. Japanese society's long-term planning horizon and comfort with megaprojects position them well for a multi-decade development program. The involvement of construction giants like Obayashi, companies that routinely manage projects spanning decades, brings project management expertise that pure aerospace companies might lack.

The mathematics of powering a space elevator climber reveals both the enormity of the challenge and the elegance of the solution. As a climber ascends, it must overcome not just its own weight but also the increasing gravitational potential energy. However, the power requirements actually decrease with altitude because Earth's gravity weakens with distance.

At sea level, lifting a 20-ton climber at 200 kilometers per hour requires approximately 2.2 megawatts of mechanical power. By the time it reaches 10,000 kilometers altitude, the same climbing speed requires only 1.5 megawatts. This decreasing power requirement partially compensates for the greater difficulty of transmitting laser power over longer distances.

The beam-powered propulsion calculations show that optimal efficiency occurs with multiple laser stations rather than a single massive transmitter. A proposed configuration uses five ground stations spaced around the equator, each capable of 50 megawatts output. As the climber ascends and the Earth rotates, different stations take turns providing power, ensuring continuous coverage without any single facility needing to track beyond 60 degrees from vertical.

Strategic placement of multiple laser stations around the equator ensures continuous power delivery while keeping beam angles manageable, solving a critical geometric challenge.

Power storage presents another fascinating optimization problem. While climbers need emergency batteries, carrying too much battery weight reduces cargo capacity. Engineers have calculated that the optimal configuration uses ultracapacitors for short-term power smoothing combined with lithium-sulfur batteries providing two hours of emergency descent capability. This hybrid system weighs just 500 kilograms while providing 4 megawatt-hours of backup power.

The economics of power generation factor heavily into feasibility studies. At industrial electricity rates of $0.05 per kilowatt-hour, the energy cost to lift one kilogram to geostationary orbit comes to about $15. Even accounting for laser inefficiency and transmission losses, the total energy cost remains under $100 per kilogram, a fraction of current launch costs. Recent analysis suggests that dedicated nuclear reactors or solar farms could provide the necessary baseline power at even lower costs.

The prospect of a 20-ton vehicle falling from space understandably raises safety concerns. Engineers have developed multiple independent systems to prevent such catastrophes, drawing lessons from aviation where redundancy has made flying remarkably safe despite the inherent risks.

The primary safety system uses distributed gripping mechanisms along the climber's length. Unlike a traditional elevator that depends on a single cable attachment, space elevator climbers would use dozens of independent grippers, each capable of supporting the entire vehicle weight. These grippers operate on different principles - some use friction, others use magnetic eddy current braking, and still others use mechanical clamping. The diversity of mechanisms ensures that no single failure mode could affect all systems simultaneously.

Secondary safety systems include deployable drag devices similar to spacecraft heat shields. If a climber becomes completely detached from the tether, these devices would increase atmospheric drag during reentry, slowing descent enough for parachutes to deploy safely. Computer simulations show that a climber falling from 1,000 kilometers altitude could land with less impact force than a typical Mars rover landing.

The laser power system itself incorporates extensive safety features. Beam intensity stays below levels that could harm aircraft or satellites passing through the beam path. Automatic shutoff systems detect any obstruction in the beam path within milliseconds, preventing accidental exposure. The infrared wavelengths used for power transmission are specifically chosen to be absorbed by water vapor in the atmosphere, creating a natural safety barrier that prevents the beam from propagating if accidentally misdirected.

Human safety remains paramount in all designs. Proposed passenger climbers would include pressurized escape pods capable of independent reentry, similar to the emergency systems on commercial spacecraft. These pods could separate from a damaged climber at any altitude and return occupants safely to Earth. The week-long transit time to geostationary orbit actually provides a safety advantage compared to rockets - there's time to diagnose problems and implement fixes rather than making split-second decisions.

The transition from laboratory demonstrations to practical prototypes has accelerated dramatically in recent years. Teams worldwide are now testing climbers on increasingly realistic tethers, revealing both unexpected challenges and promising solutions.

The European Space Agency's test facility in the Netherlands uses a 2-kilometer vertical tether to test climber prototypes in controlled conditions. Their latest tests achieved climbing speeds of 50 meters per second, though only for short durations before thermal management systems became overwhelmed. The data from these tests feeds directly into next-generation designs with improved cooling systems.

MIT's Space Systems Laboratory has taken a different approach, using underwater testing to simulate the microgravity environment climbers would experience at high altitudes. Their submersible prototypes use the same gripping mechanisms and power systems as orbital designs but operate in a neutral buoyancy tank. This testing revealed that climbers tend to develop oscillation modes that could cause tether damage, leading to the development of active damping systems.

Private companies have made impressive strides too. SpaceVoyage Ventures demonstrated a climber that can operate continuously for 72 hours, the longest duration achieved to date. Their prototype uses regenerative braking to recover energy during descent, improving overall system efficiency by 15%. This energy recovery becomes crucial for the economics of space elevator operation, where downward cargo transport could partially power upward climbs.

The most ambitious current test involves a 10-kilometer tether deployed from a stratospheric balloon. This test, scheduled for 2026, will demonstrate climber operation through multiple atmospheric layers, including the challenging transition through the jet stream where wind speeds exceed 200 kilometers per hour. Success would validate the feasibility of the lower portion of a space elevator, arguably the most technically challenging segment.

"Every kilometer we climb in testing brings us closer to orbit. The challenges are real, but so is our progress."

- Yuki Yamamoto, JAXA Space Elevator Project

The financial landscape for space elevator development has shifted dramatically in recent years. While government funding remains important, private investment now drives much of the innovation. Venture capital firms have invested over $500 million in power beaming and climber technologies since 2020, recognizing applications beyond just space elevators.

Star Catcher Industries raised $12.5 million in their latest funding round, with investors attracted by near-term applications like powering drone swarms and emergency communications systems. The dual-use nature of climber technology makes it attractive to investors who might shy away from pure space ventures. Technologies developed for space elevator climbers have immediate applications in automated warehouses, construction robotics, and vertical farming.

Government investment continues through agencies like DARPA, which has allocated $100 million for optical wireless power development through 2027. NASA's Innovative Advanced Concepts program funds multiple climber-related studies, focusing on technologies that could also benefit lunar and Mars infrastructure. The Chinese Academy of Sciences announced a 10-billion yuan ($1.4 billion) program for space elevator research, though details remain limited.

The timeline for operational space elevators depends heavily on progress in carbon nanotube manufacturing, currently the primary bottleneck. Optimistic projections from Obayashi Corporation suggest a demonstration system by 2040 and commercial operation by 2050. More conservative estimates from NASA push those dates to 2060 and 2075 respectively. However, intermediate milestones look increasingly achievable. Prototype climbers operating on 100-kilometer tethers could demonstrate viability by 2030.

The development pathway follows a logical progression. First, perfect wireless power transmission for terrestrial applications. Second, demonstrate climbers on progressively taller test structures. Third, deploy a partial space elevator to low Earth orbit for technology validation. Finally, extend the system to geostationary orbit for full operational capability. Each stage generates revenue and knowledge that funds the next phase, making the enormous investment more manageable.

The prospect of laser-powered climbers ascending space elevators raises profound questions about humanity's future. If we can reduce the cost of space access by two orders of magnitude, entire new industries become possible. Orbital manufacturing could produce materials impossible to create in Earth's gravity. Solar power stations could beam clean energy to Earth. Mining operations could extract resources from asteroids without the environmental impact of terrestrial mining.

For engineers and technicians, the space elevator industry represents a massive opportunity. Skills in laser optics, power electronics, robotics, and materials science will be in high demand. Universities are already adapting curricula to prepare students for this emerging field. The Colorado School of Mines offers a graduate certificate in space resources, while Tokyo Institute of Technology has established a dedicated space elevator research laboratory.

The societal implications extend beyond just economics and employment. Cheap access to space could democratize opportunities currently reserved for governments and billionaires. Small nations could afford their own satellites. Universities could conduct microgravity research. Even individuals might afford space tourism, transforming it from an exclusive luxury to something like international air travel today.

A functioning space elevator would reduce launch costs by 98%, transforming space from an exclusive frontier to an accessible destination for humanity.

Environmental considerations also factor prominently. While rocket launches produce significant emissions, laser-powered climbers would operate on electricity that could come entirely from renewable sources. A functioning space elevator could actually help combat climate change by enabling the deployment of space-based solar power stations or orbital sunshades to manage Earth's temperature.

The psychological impact shouldn't be underestimated either. Throughout history, transportation breakthroughs have transformed how humans see themselves and their place in the universe. Just as ships enabled global exploration and aircraft shrank the world, space elevators could make humanity a truly spacefaring civilization. Children growing up with space elevators might view working in orbit as naturally as we view flying to another continent.

The journey from science fiction concept to engineering reality has been longer than early space elevator enthusiasts anticipated, but the destination now appears within reach. The successful demonstration of high-efficiency laser power transmission, the steady improvement in climber prototypes, and the growing investment from both governments and private companies all point toward an inflection point in development.

What seemed impossible just a decade ago - beaming megawatts of power through turbulent atmosphere to a moving target - has been proven feasible. The remaining challenges, while significant, are engineering problems rather than fundamental physics barriers. With continued progress in carbon nanotube manufacturing and laser technology, the question has shifted from "if" to "when" humanity will build its first space elevator.

The laser-powered climbers that will make space elevators possible represent more than just a new transportation technology. They embody humanity's refusal to accept the limitations that have confined us to Earth's surface for our entire existence as a species. Every successful test, every efficiency improvement, every investment brings us closer to the day when traveling to orbit becomes as routine as taking an elevator to the top floor of a skyscraper.

That future might arrive sooner than we think. As one Japanese engineer recently noted, a child born today might celebrate their 25th birthday aboard a space elevator climber, watching Earth shrink below as they ascend toward the stars on an invisible beam of light. The climb to space has begun - we're just building the elevator.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.