Ice Volcano on Ceres Hints at Hidden Ocean

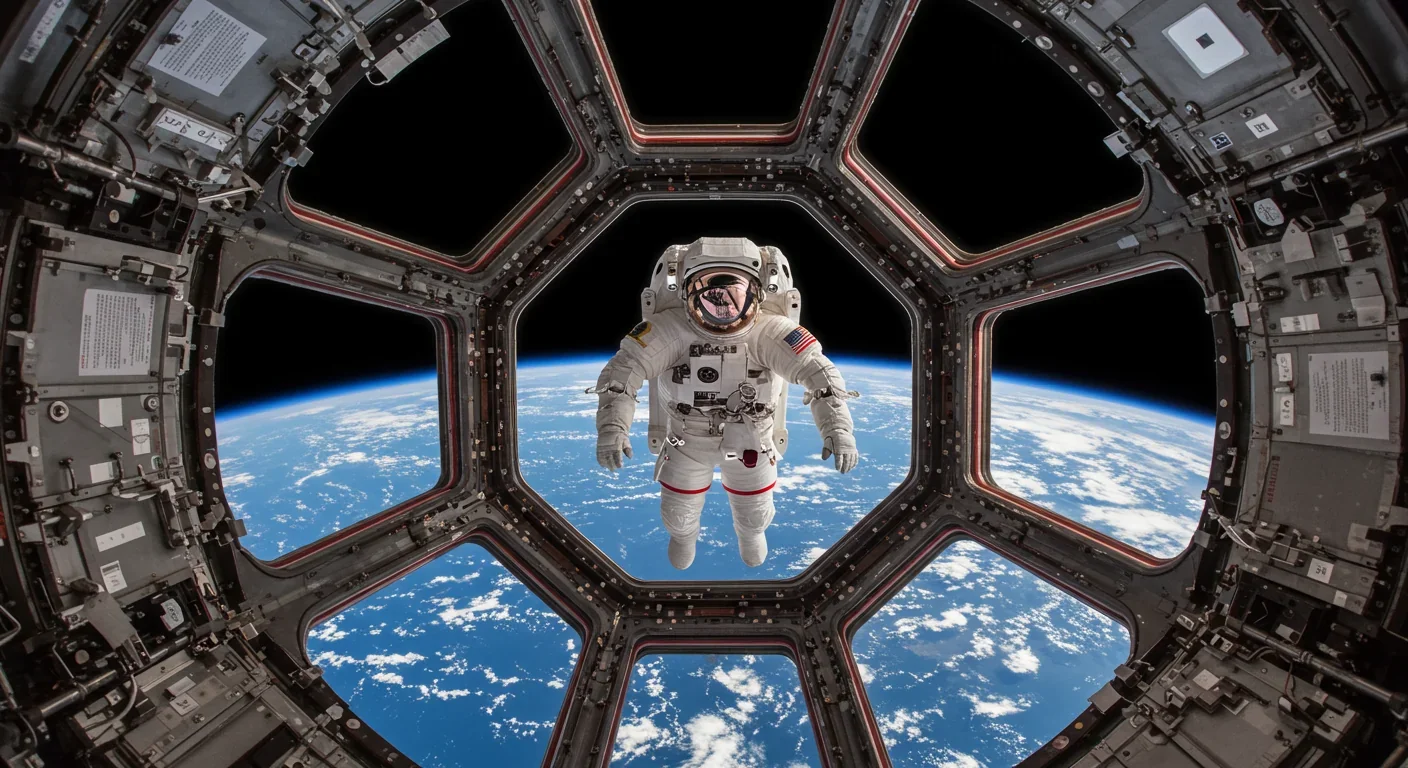

TL;DR: When astronauts view Earth from space, they experience the overview effect: a profound psychological shift that dissolves borders, reveals planetary fragility, and fosters unity consciousness. This transformation has inspired environmental movements and challenges us to adopt a spacefarer perspective without leaving the ground.

When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon in 1969, he uttered one of history's most famous lines about taking a giant leap for mankind. But later, reflecting on seeing Earth from space, Armstrong said something far more personal: "I didn't feel like a giant. I felt very, very small."

That shift from triumph to humility captures what researchers call the overview effect, a profound psychological transformation that happens when humans view Earth from orbit. It's not just about seeing our planet from a new angle. It's about experiencing a cognitive earthquake that reshapes how astronauts understand their place in the universe.

The term "overview effect" was coined by author Frank White in his 1987 book The Overview Effect: Space Exploration and Human Evolution. White described it as a cognitive shift where astronauts suddenly perceive Earth as a fragile, interconnected system floating in the vastness of space. Borders disappear. Political divisions seem absurd. The atmosphere appears paper-thin.

What makes this experience particularly striking is its consistency. Roughly 500 people have traveled to space, and an overwhelming majority report some version of this transformed perspective. Astronaut William Anders, who photographed the famous "Earthrise" image during Apollo 8 in 1968, later reflected that the mission's real discovery wasn't the moon at all. "We set out to explore the moon and instead discovered the Earth," he said.

The overview effect isn't just poetic language. Research published in Frontiers in Psychology has documented measurable psychological changes, including reduced stress, heightened creativity, and increased feelings of connection and awe. Scientists have even identified physiological markers, such as changes in vagal tone, that correlate with these emotional shifts.

If the overview effect has an origin story, it begins with a photograph. On December 24, 1968, during humanity's first crewed mission to lunar orbit, astronaut William Anders looked out his window and saw something no human had witnessed before: Earth rising above the moon's stark, gray horizon.

He grabbed his Hasselblad camera and captured what nature photographer Galen Rowell would later call "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken." The image showed our planet as a brilliant blue-and-white marble suspended in infinite darkness, a fragile oasis in an otherwise hostile cosmos.

The Earthrise photograph arrived at a pivotal moment. The late 1960s were marked by social upheaval, environmental degradation, and Cold War tensions. This single image helped catalyze the environmental movement, appearing on the cover of the Whole Earth Catalog's Spring 1969 issue and inspiring a generation to think differently about planetary stewardship.

Anders himself experienced a profound personal transformation. The devout Christian astronaut later admitted that seeing Earth from space "really undercut my religious beliefs." He became friends with atheist scientist Richard Dawkins, illustrating how the overview effect can fundamentally alter worldviews.

Modern astronauts have access to something their predecessors didn't: the International Space Station's cupola, a seven-window observation module installed in 2010. Astronaut Nicole Stott described the cupola's impact in vivid terms: "You really get the curvature of the Earth, and you get much more of a feeling of a planet hanging in space."

What began as an operational addition to the ISS has become its primary relaxation feature. Astronauts spend their downtime there, gazing at Earth in what researchers call "Earthgazing" sessions. Studies show these sessions reduce cognitive and emotional stress while cultivating emotions like gratitude, reverence, humility, and belonging.

Emily Calandrelli, who flew on Blue Origin's NS-28 mission in 2024, captured the immediacy of the experience: "We got to weightlessness, I immediately turned upside down and looked at the planet and then there was so much blackness." That confrontation with the void, combined with Earth's vivid presence, creates an emotional intensity that many astronauts struggle to articulate.

The testimonies share common themes. Astronauts describe feeling overwhelming unity, a sense that all humans are fundamentally connected. They report heightened awareness of Earth's fragility. Political and national boundaries, so prominent on maps, become invisible and meaningless from orbit. One astronaut simply observed that "the borders and divisions that separate nations on maps are invisible from space."

Scientists are beginning to understand what happens in the brain during these transformative moments. The overview effect shares characteristics with awe, a complex emotion triggered by experiences that are vast, novel, and challenge our existing mental frameworks.

Research on awe experiences shows they activate multiple brain regions simultaneously, including areas involved in attention, emotion regulation, and self-perception. When people experience awe, their sense of self temporarily shrinks, making them feel smaller yet paradoxically more connected to something larger.

This "small self" phenomenon explains why Armstrong felt diminished rather than enlarged by his moonwalk. It also explains why astronauts consistently report feeling part of a unified whole rather than separate individuals representing different nations.

The neurological effects extend beyond the moment itself. Awe experiences can trigger lasting changes in perspective, behavior, and values. People who regularly experience awe show increased prosocial behavior, greater environmental concern, and enhanced creativity. They become more patient, less materialistic, and more willing to help others.

For astronauts, this isn't a brief meditation session or a hike in nature. It's an extended immersion in arguably the most awe-inspiring view humans can experience. One study found that the overview effect represents one of the most profound instances of self-transcendent experience possible, comparable to mystical or religious experiences in its intensity and life-altering impact.

The real question isn't whether the overview effect is real, it's whether it matters beyond the tiny fraction of humans who experience it directly. Can one person's transformed consciousness translate into broader social change?

History suggests it can. Following their space missions, numerous astronauts have become environmental advocates, international cooperation champions, and voices for global unity. They leverage their unique credibility as explorers to communicate urgent messages about planetary stewardship.

Ron Garan, who spent 178 days in space, became particularly vocal about what he calls "the big lie" that humanity is living: the idea that we can have infinite economic growth on a finite planet. After seeing Earth's thin atmosphere from orbit, Garan dedicated himself to sustainability work and wrote extensively about the need for systemic change.

The environmental movement has long used space imagery to convey planetary fragility. Earth Day, first celebrated in 1970, prominently featured photos from space. Climate activists regularly invoke the "pale blue dot" perspective. Even the Artemis 2 mission patch incorporates cloud patterns from the original Earthrise photograph, demonstrating how environmental symbolism has become embedded in space exploration itself.

But translating individual revelation into mass movement remains challenging. As author Larissa Scherrer notes, "We don't need to float 250 miles above our planet to understand its fragility and interconnectedness. We just need to start thinking like those who have."

That aspiration drives several initiatives aimed at bringing space perspectives to Earth-bound humans. Virtual reality programs simulate orbital views, allowing users to experience approximations of Earthgazing. Documentary projects like "Overview" and "A Beautiful Planet" use IMAX footage from the ISS to convey the astronaut perspective to mass audiences.

Commercial space tourism promises to expand access, though at eye-watering prices. Blue Origin, SpaceX, and Virgin Galactic are flying paying customers to the edge of space, giving brief but genuine overview experiences. Early space tourists have reported emotional reactions matching those of professional astronauts.

Yet technological simulations and expensive joy rides may miss the point. The overview effect isn't just about seeing Earth from space, it's about the cognitive shift that follows. Some researchers argue we can cultivate similar perspective changes through meditation, philosophical reflection, or intentional engagement with Earth systems science.

Consider that indigenous cultures have maintained holistic, interconnected views of Earth for millennia without leaving the planet. The overview effect might not reveal anything genuinely new so much as it strips away cultural conditioning that keeps us from seeing what was always there: one planet, one biosphere, one human family.

The overview effect has concrete applications in spacecraft design and astronaut wellbeing. Research suggests that incorporating deliberate relaxation spaces with Earth views, like the ISS cupola, significantly reduces astronaut stress and enhances creativity. Future missions to Mars and beyond might benefit from dedicated Earthgazing areas, at least until our planet becomes too distant to see clearly.

Mental health professionals studying astronaut psychology recognize the overview effect as a protective factor against the psychological challenges of spaceflight: isolation, confinement, danger, and separation from loved ones. The positive emotions generated by Earthgazing appear to buffer against anxiety and depression.

On Earth, the overview perspective informs circular economy initiatives, sustainable design principles, and systems thinking approaches to business. Companies are increasingly adopting frameworks that recognize planetary boundaries and interconnected impacts, essentially trying to operationalize astronaut consciousness without leaving the ground.

Educational programs use space imagery to teach systems thinking to students, helping young people grasp concepts like climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource limits. Some curricula explicitly reference the overview effect as a model for the kind of perspective shift needed to address global challenges.

There's an uncomfortable irony in the overview effect: the activity that generates it, spaceflight, is extraordinarily resource-intensive and environmentally costly. Launching rockets burns enormous quantities of fuel and releases significant emissions. Space tourism, in particular, faces criticism as an extravagant luxury with substantial carbon footprints.

Defenders argue that spaceflight's inspirational value and technological spinoffs justify its environmental cost. They point to satellite technology that monitors climate change, enables renewable energy optimization, and supports environmental research. Without space programs, they contend, we'd lack the very images and perspectives that inspire environmental action.

Critics counter that we don't need more astronauts or tourists experiencing the overview effect; we need the billions of people on Earth to act on the knowledge we already possess. Every dollar and resource invested in space tourism, they argue, could instead support direct environmental restoration or climate adaptation.

This tension reveals a deeper question about how societies change. Do we need transformative individual experiences that then cascade through culture? Or do we need structural, political, and economic changes that make individual enlightenment unnecessary? Perhaps we need both, operating in tandem.

As space access expands, the overview effect may become less exclusive. Within the next decade, thousands rather than hundreds of people might experience orbital perspectives directly. Current estimates suggest about 500 living people have seen Earth from space; that number could grow exponentially.

But scale creates its own questions. If everyone can experience the overview effect, does it retain its transformative power? Do we risk turning a profound shift in consciousness into just another tourist attraction, complete with selfies and social media posts?

The answer may depend on how we integrate these experiences into broader cultural narratives. Astronauts don't just see Earth differently in space; they carry that perspective back and share it, write about it, advocate from it. The overview effect matters not because of the moment itself but because of how that moment reverberates through subsequent choices and actions.

Some researchers are exploring whether the cognitive shift can be deliberately cultivated without spaceflight. If the overview effect is ultimately about interconnection, humility, and planetary awareness, perhaps contemplative practices, education, or even psychedelic experiences could generate similar transformations. The question becomes: what's essential, seeing Earth from space or adopting the worldview that follows?

Frank White, who coined the term, suggested that humanity might eventually develop a "spacefarer civilization" where the overview perspective becomes baseline consciousness rather than rare revelation. We'd make decisions as if we'd all seen Earth from orbit: fragile, borderless, and precious.

That future remains speculative, but elements are emerging. Climate science gives us intellectual understanding of planetary interconnection. Satellite imagery provides daily views from space. Social media enables instant global communication that reinforces our fundamental connectedness. We have the information astronauts have; what we may lack is the emotional certainty.

Perhaps the overview effect's greatest contribution isn't the perspective itself but the proof that such perspective shifts are possible. If seeing Earth from space can fundamentally alter how astronauts think about borders, conflict, and environmental responsibility, then psychological transformation isn't just aspirational philosophy. It's documented reality.

The challenge is scaling that transformation. We can't send eight billion people to orbit, nor should we try. But we can ask what equivalent experiences might work on Earth. What would it take for someone who's never left the ground to suddenly perceive the planet as astronauts do: unified, vulnerable, and irreplaceable?

The astronauts have shown us it's possible to see ourselves differently. Now we need to figure out how to share that vision with everyone who'll never leave the atmosphere but whose choices determine whether the fragile world those astronauts describe will endure. Because in the end, the overview effect isn't about space. It's about Earth, and our responsibility to the only home we have.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

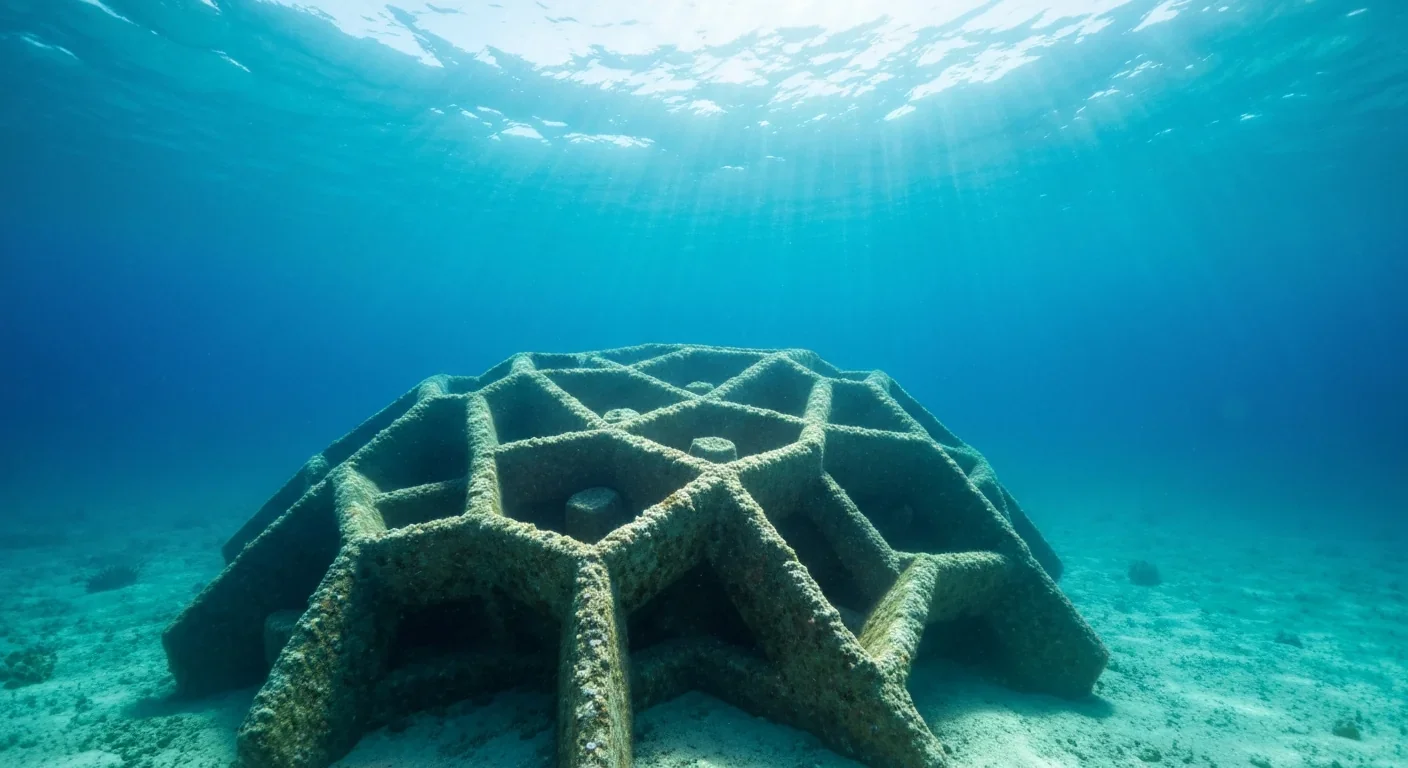

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

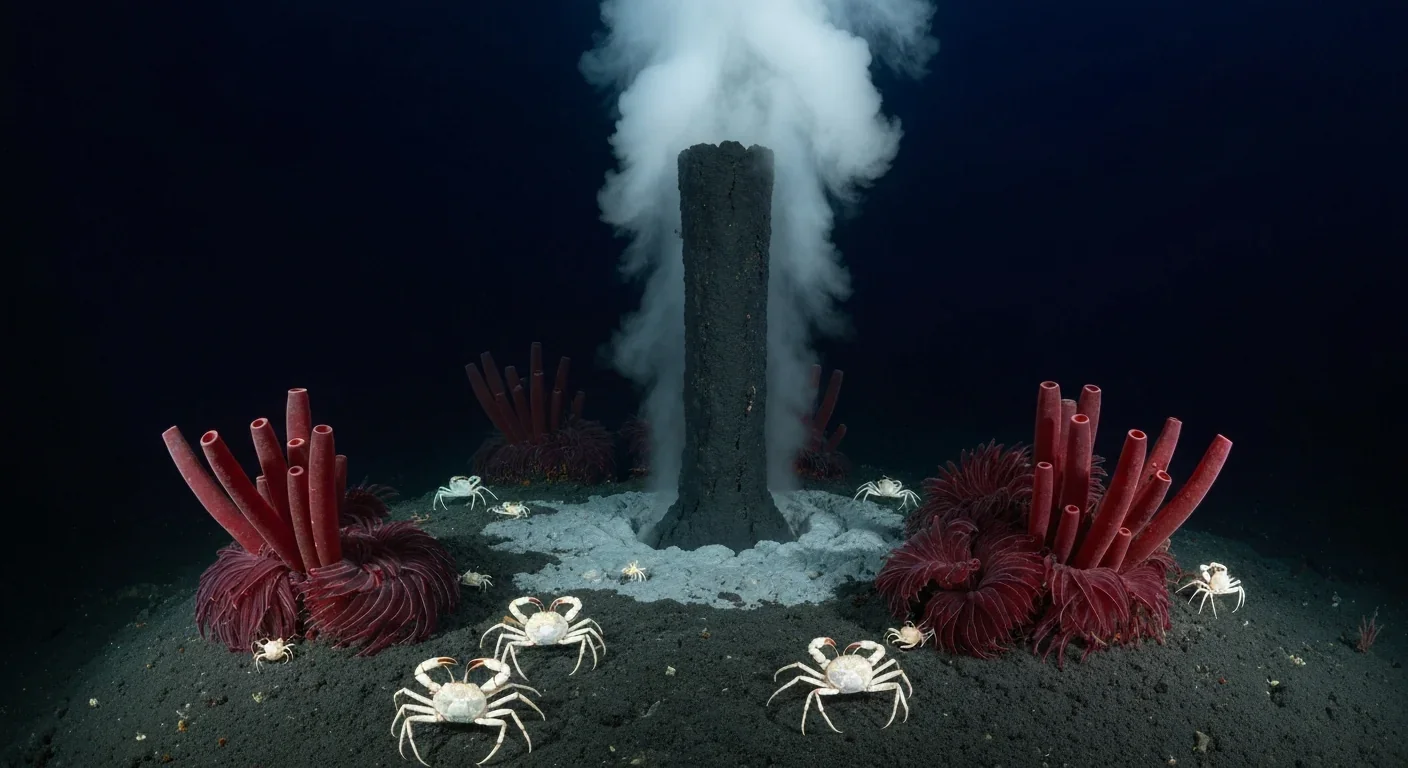

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

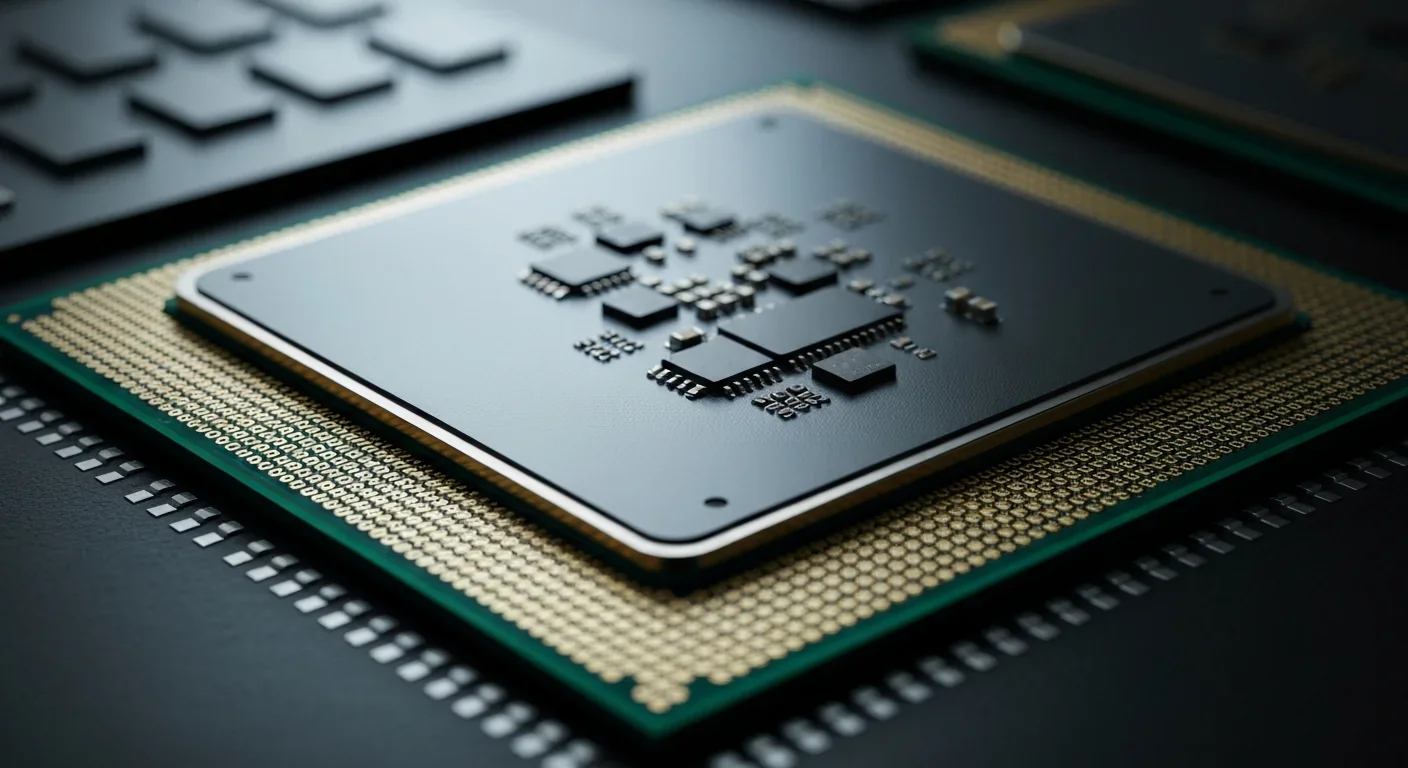

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.